The Rape of Europa (48 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

On July 18, after talking to local commanders, he informed Kesselring’s headquarters, and also those of SS General Karl Wolff, who controlled all SS operations in Italy and was directly responsible to Himmler, that he was “taking in hand immediately supervision and direction of evacuation measures by our troops.” He again did not bother to tell Poggi and left town without even saying goodbye, taking the Cranachs with him to the German embassy, now located at Fasano on Lake Garda. There, on July

22, he met with Wolff, who issued a special order authorizing the removal from any

ricovero

which could still be reached of “whatever could be saved of the endangered works of art belonging to the Uffizi and Palazzo Pitti in Florence,” and gave Langsdorff eight precious trucks for the operation. The convoy left almost immediately for Florence, and arrived there at dawn on July 28 after three straight days and nights on the road.

38

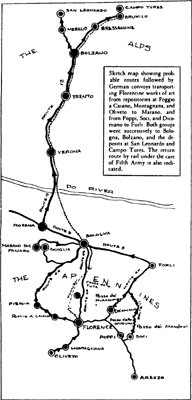

Frederick Hartt’s map of the complicated travels of the Florentine works

While this group was en route, another SS colonel by the name of Baumann, utterly uninformed in art matters but aware of Wolff’s orders, had arrived in Florence and told Poggi that all the Florentine treasures including those in the city were to be moved. The unlikely duo of Poggi and the German consul were able to put him off by saying that everything except a number of huge sculptures had already left, and with straight faces toured the hapless Nazi around the biggest and least movable things they could find, showing him such large works as Cellini’s

Perseus

and the bronze doors of the Baptistry. They did not bother to show him the more movable Uffizi drawings collection, or the masterpieces from all over Tuscany which had been hidden in secret passages beneath the museum.

39

But Poggi could not fob off Langsdorff as he had Baumann, and when the Kunstschutz chief arrived the Superintendent was forced to brief him on which

ricoveri

were in the greatest danger. Study of the military situation immediately indicated the sculpture deposit at Dicomano. Without allowing his men any sleep, Langsdorff ordered them to drive to the deserted

little town, where the only building still standing was the oratory in which the works were stored. The next three days were spent cramming the heavy statues onto the trucks with whatever machinery could be devised. It was not easy duty: the presence of the convoy attracted air strikes which constantly interrupted the work, and the drivers were forced to live on vegetables foraged from abandoned gardens, which they cooked into a sort of stew in a pot found in the wreckage of a house.

On the evening of July 30 the loaded convoy headed not back to Florence but to Wolff’s headquarters at Verona. As the trucks crossed the Po on a rickety pontoon bridge in the dark of night, Allied bombs split open the cab of one and wounded its driver. Doggedly they continued on, using back roads to avoid further raids, and arrived at Verona at dawn on August 4.

The Fascist government, meanwhile, worried by this behavior on the part of its “allies,” began to press for the return of the Florentine objects to their custody. But Wolff was determined to keep them under his control, and on August 5 Langsdorff was told that the Gauleiter of the new “Gau Tirol” had been ordered to find storage for the wandering masterpieces near Bolzano, well within the northern areas annexed to the Reich. The Gauleiter was carefully instructed not to choose a site near the Swiss border lest Mussolini somehow manage to whisk the works across it into neutral territory.

While the Dicomano shipment continued its journey up to Bolzano, Langsdorff ordered his assistants to return to Marano sul Panaro to arrange transport for the 291 pictures abandoned there previously, and these, also unbeknowst to the Italians, followed the sculptures toward Bolzano on August 10. It was none too soon. Perhaps tired of war, an officer of the unit protecting Marano had been entertaining the locals by driving several truckloads of the paintings around, “improvising shows here and there, in the open air, under the porticoes and in villas. The last halt… was at Villa Taroni, where a ball was given, with torchlight illuminations, while the paintings, a Titian among them, decorated the rooms. And sad to say, some well known Italian families, who were spending the summer in that neighborhood, came to the ball.”

40

An interim attempt to take the cache from the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano, eleven miles northwest of Florence, on August 8, had been abandoned when Langsdorff, accompanied by SS General Wolff’s aide-decamp, was driven back by artillery fire. On August 19 Langsdorff’s deputy Reidemeister was able to return to Poggio, where he found the castle full of refugees who were using the cases of paintings as bedsteads and cooking among them on alcohol stoves. Evidence that the lull in the artillery

barrage was not entirely coincidental is provided by a bizarre telegram sent at the exact same time from the German legation in Bern (via the Swiss Foreign Office) to the Department of State in Washington:

German authorities Italy have stored in Villa Reale Poggio at Caiano … valuable artistic collections and archives concerning Tuscan Renaissance works…. German Government states there are no (repeat no) German troops in neighborhood Villa Reale and villa itself not used (repeat not) used for military purpose…. German Government desires inform American and British Governments it desires avoid bombardment or destruction Villa Reale.

41

This was reinforced by similar announcements on the radio. Two days later, on August 23, thirty cases were finally removed from Poggio in the midst of renewed shellfire and taken off toward Bologna over the pitted roads. On their way back to base, not wanting to miss anything, the Germans collected forty-one pictures discovered by troops at the Villa Podere di Trefiano; these were instantly recognized by Langsdorff as being from the collection of Goering’s erstwhile dealer friend, Count Contini Bonacossi.

At the same time other units had moved 196 more pictures and 69 cases of sculpture, among them Donatello’s

St. George

and

David

, Michelangelo’s

Bacchus

, and the Medici

Venus

, from the Villa Bocci and Castello Poppi near Bibbiena. The latter pickup had all the trappings of a Grade B movie: after a series of harassments and threats the townspeople were ordered at gunpoint to remain in their cellars while the town was mined and searches were made for hidden arms. While the citizens huddled miserably in total darkness, the Germans broke into the

ricovero

, tore open cases, and loaded what seemed to be a random selection into a single truck. In fact, the paintings jammed into the vehicle were carefully chosen and ran heavily to the northern schools so beloved of Hitler. Three Raphaels, two Botticellis, and Titian’s

Concert

plus a Watteau and a del Sarto or two were thrown in for good measure. What was left behind was more amazing: Botticelli’s

Birth of Venus

, Leonardo’s

Adoration of the Magi

, and Michelangelo’s

Doni Madonna

were scattered in the wide-open castle among the litter of the violated packing cases. Before they departed the Germans apologized to the mayor for not being able to take everything away, told him to protect the villa, and blew up the town gate and the only access road to the village.

By September 7 twenty-two truckloads containing 532 paintings and 153 sculptures, representing nearly half of the best Florence had to offer, had finally reached their mountain refuges. Arrangements at the arrival

end had not been much easier to make than those in the battle areas around Florence. Dr. Reidemeister had arrived with the first shipment at the assigned storage area, only to find that the entrances were so narrow that the trucks could not get in. This was just as well, as no one had noticed the presence of a major ammunition dump next door to the damp premises. The Gauleiter of the Tirol suggested that they continue on to the safety of Innsbruck or Bavaria, but Reidemeister later claimed that he had refused to do so as “it was the Führer’s wish to safeguard these valuables on Italian soil, so that no one abroad should accuse them of looting.”

Germans unloading Uffizi pictures at San Leonardo (Kunstschutz photo)

An alternative site was not easily thought of; the area was full of Italian Partisans and Allied bombing was intense. Leaving the truckloads of art behind, and knowing that more were en route, Reidemeister, Dr. Josef Ringler of the Ahnenerbe’s South Tirol Culture Commission, and the local Fine Arts Superintendent rushed off to look for another refuge in the remote mountain passes. The mayor of San Leonardo in Passiria showed them an abandoned jail which was perfect, but too small to hold everything. They rejected an old paper mill and one château half full of agricultural tools, offered by a kindly countess. But a coach house at the

Schloss Neumelans in Sand at Campo Tures, offered by another lady, proved ideal, and Reidemeister arranged for the trucks from Dicomano to be unloaded there on August 11.

On August 27 another shipment, which contained the famous Cranach

Adam

and

Eve

, got as far as an Army barracks in Bolzano and then ran out of gas. Rushing down to deal with this latest crisis, Ringler was shocked to find that the paintings had been loaded into the trucks without any packing materials or protection. On September 1, the quest for fuel having been unsuccessful, Ringler received the following telegram from General Wolff’s headquarters: “Please load the five truckloads onto closed furniture vans, harness with horses or oxen, and convey to deposits.” This being patently impossible, the search for gasoline went on. Ringler was of course competing with the retreat of the entire German Army across the Apennines. Five hundred fifty liters were finally produced on personal orders of General Wolff, but by now the weather was so bad that the convoy had to spend yet another day on the road before it was unloaded at Schloss Neumelans on September 5. Two days later, five more loads containing confiscated Jewish collections and the Contini pictures, all packed in excelsior taken out of fruit baskets found in a convent, went up to join the rest. The unloading took days, and the refuges were now full to bursting.

The remarkable and hasty evacuation of these works to the north coincided exactly with the Allied advance on Florence, which had never been formally declared an open city by either side. Allied reluctance was due to the very mixed signals being received from the Germans: on the one hand, Hitler had declared Florence to be “the jewel of Europe” and on several occasions had reaffirmed his desire that it remain unharmed. But on the other, he had again on July 3 exhorted his troops and Kesselring to hold the Arno line, to which Florence was just as pivotal as Monte Cassino had been to the Gustav line.

Florence, unquestionably an important communications and transportation center that would be useful to both armies, remained crammed full of German troops despite Hitler’s declarations. Kesselring had left Rome and its bridges intact, thereby facilitating the rapid advance of Allied troops through the city, an act which Hitler now regretted. There was no question in Kesselring’s mind that the situation in Florence would be the same. By mid-July tough retreating German paratroop divisions were taking up defensive positions south of the city, where on the nineteenth Hitler again ordered them to make a stand. According to one witness at Hitler’s headquarters, he specifically declared that Florence itself was not to be a battleground, a statement which was communicated to the Allies through

the Vatican, and he confirmed this in conversations with Mussolini the next day.

Other books

His Remarkable Bride by Merry Farmer

Mayhem in Margaux by Jean-Pierre Alaux, Noël Balen

Her Pirate to Love: A Sam Steele Romance by Michelle Beattie

Talisman 2 - The Sapphire Talisman by Pandos, Brenda

The Boardroom (New Adult Contemporary Romance) by Macguire, Jacee

Believe by Allyson Giles

Tank's Redemption: Red Devils M.C. (Red Devils MC Book 4) by Michelle Woods

Stone Cold Dead by James W. Ziskin

The Pornographer by John McGahern

7 Years Bad Sex by Nicky Wells