The Rape of Europa (43 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Help did not come for five exhausting weeks, during which time Hammond had little idea of how the rest of Sicily had fared. Most of the information compiled in the United States on Italian personnel, when it did finally get to him, had proven so out of date as to be useless. The famous maps, which he had hoped to dispatch to the front, never came at all—they had been carefully stored in the library of the training center at Algiers. It was not until early September that the arrival of his British counterpart, Captain F. H. J. Maxse, and an Italian-American sergeant by the name of Nick Delfino enabled him to tour, all too briefly, the rest of the island, Delfino “by methods too devious to bear the cold light of print” having produced a small, decrepit car which soon became known as “Hammond’s Peril.” It was the first in a long line of similar vehicles without which considerable segments of Europe’s patrimony would not have been saved.

On their forays Hammond and Maxse discovered that most movable works of art had been safely stored, and that the passage of the armies had been so fast that little damage and looting had taken place. The problem, they would find, was not so much battle, but occupation and the limbo period which preceded it, when the natives were apt to succumb to temptation and troops freed from the simple need to survive turned to souvenir collecting and graffiti painting. On more than one historic wall Hammond observed German and American inscriptions side by side. But the Allied forces had moved along so quickly that problems of this nature were few.

The Monuments men did have to evict officers camping on rare plants in the Botanical Gardens and arrange protection for the ruins of Palermo’s magnificent National Library, whose bombed stacks full of rare books lay open like a sliced pomegranate to passing thieves and the elements. But in general the damage they found, except in the regions of Catania and Messina, where the battles had gone on for weeks, was minor, and most of their time was spent in brokerlike negotiations for AMGOT funds for emergency repairs. These were so generously distributed at first that many were tempted to exaggerate their need. The Cardinal Archbishop of

Palermo, who had early established a friendly rapport with General Patton, tried to slip in the complete refurbishment of his palazzo to its original splendor as “essential” work. Patton himself, lodged in the magnificent but dusty gloom of the Norman Palace, seat of the former Kings of Sicily, had asked for redecoration money. The denial of these requests would severely tax the diplomacy of the Military Government.

43

Hammond and Maxse, not yet having Woolley in office to advise them otherwise, sent fat detailed reports on their experiences back through channels to the War Department. Fortunately, Hammond also wrote long private letters to colleagues at home, full of suggestions for improvements in the system. Much the wiser, he begged for more information and reinforcements. Sicily, with its friendly people and relatively sparse monuments, had challenged them to the utmost. And now the whole of Italy, filled with infinitely more precious things, already being invaded and bombed by Allied forces, lay before them, the last nation to be occupied by the Reich.

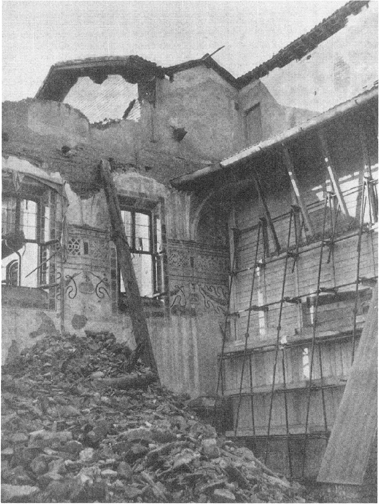

Protection measures vindicated: Leonardo’s

Last Supper

is safe behind the structure at right.

IX

THE RED-HOT RAKE

Italy, 1943–1945

Here is this beautiful country suffering the worst horrors of war, with the larger part still in the cruel and vengeful grip of the Nazis, and with a hideous prospect of the red-hot rake of the battle-line being drawn from sea to sea right up the whole length of the peninsula.

—Sir Winston Churchill

May 24, 1944

The invasion of Sicily had been a stunning blow to Benito Mussolini. The once flamboyant dictator had lost support in all quarters, even from his own Fascist party. On July 25, 1943, the Party’s Grand Council voted for the restoration of constitutional monarchy, and the King, after calling Mussolini to the Royal Palace, fired him, arrested him, and bundled the surprised Duce off to jail in an ambulance. Marshal Pietro Badoglio was called upon to head a new government.

The Allies, divided on just where they would move after Sicily, reacted slowly to these events. After tough negotiations, they agreed on an invasion of France in May 1944. Troops from Sicily were to be sent to England to begin training, and a reduced force would be used in Italy, where, with the presumed help of Badoglio’s forces, a quick advance to a line from Livorno to Ancona was foreseen. There the Allies, well placed for bombing Germany, planned to halt.

In May, Hitler, perfectly aware that the Italians might cave in easily come an Allied invasion, had secretly ordered Rommel to set up a new Army group for the north of Italy. The Brenner Pass defenses were to be strengthened and troops infiltrated into the north. Italian performance in Sicily did nothing to improve the Führer’s confidence. Still, Mussolini’s fall came to Hitler as a nasty surprise. Enraged, the Führer at first wanted

German troops to take over Rome—the Vatican included—arrest the whole government, and kidnap the Royal Family. Goebbels, appalled at the negative propaganda possibilities, managed to talk Hitler out of seizing the Vatican, and his generals into limiting their response to the sending of a paratroop force to the Rome airport. But German preparations did not cease. All during August troops continued to move toward the Italian theater, while precise plans were drawn up for the occupation of the country. At receipt of the code word “AXIS” German forces would disarm the Italian Army, restore the Fascist government, and regard Italy as one more occupied country.

To Hitler the Italian situation was not merely an affair of state. It was a personal betrayal. No one symbolized the duplicity of his former ally more than Princess Mafalda, daughter of the King and wife of Prince Philip of Hesse, who had procured so many works of art for Hitler and Goering over the years. When the Prince visited the Führer’s Eastern Front headquarters a few weeks after the debacle, he was politely but firmly detained there. The rest of the entourage now “avoided him as if he had a contagious disease.”

1

On September 9 the Führer had the couple sent to separate concentration camps, where Mafalda eventually perished.

How much of Italy Hitler could hold would depend on the timing and location of the Allied invasion. When the British Eighth Army finally landed in Calabria on September 3, German planners assumed that the Allies would follow up this incursion with an airborne seizure of Rome in combination with Italian forces and amphibious landings on the coast near the capital. But by September 8, when after much agonizing the Badoglio government surrendered to Eisenhower and fled south, there were no Allied troops anywhere near the Eternal City. Field Marshal Kesselring immediately broadcast the code word “AXIS,” and the crack German paratroops so fortuitously sent to Rome moved in.

What remained of the Fascist government was evacuated to Lake Garda. Unbeknownst to them, a new frontier had been drawn in the north: the territory down to Verona and as far over as Trieste was incorporated into the Reich under the administration of the Gauleiters of the Tirol and Carinthia, negating the Führer’s generous 1938 gesture, which had left this long-disputed area in Italian hands in return for the Duce’s support for the Anschluss. One day after these arrangements had been made, Hitler’s friend Mussolini, his territories thus considerably diminished, was rescued in a daring commando raid and reinstalled as “Head of State.” These quick actions and the hesitations of the Allies had allowed the Thousand-Year Reich to be extended to a line south of Naples reaching from the beautiful beach town of Salerno across to Bari in the east.

In the early years of the war the directors of the Italian Belli Arti, like their colleagues in other nations, had put the most precious contents of their museums in refuges, or

ricoveri.

The museum administration of Naples had sent theirs to the vast and isolated Benedictine monastery at Montevergine high above the city and about thirty miles to the east. There and at another repository at Cava, near Salerno, were eventually concentrated more than 37,000 works of art from the Royal Palace, the major museums, and private collections. The contents of the Civic Museum, as well as nine hundred cases of the most ancient documents from the Neapolitan Archives, went to the Villa Montesano near Nola. Transport was not easy: covered trucks were hard to come by, the roads were punctured by bomb craters, and anything that moved was the target of Allied dive bombers. Each trip to the refuges became an adventure, but the curators persisted, and by the early summer of 1943 nearly sixty thousand objects had been made as safe as seemed possible.

2

The manner of the Allied progress in eastern Sicily, where German resistance was strong, was, however, most disturbing. The troops had not just stuck to the roads as the Germans had done in France. The battle had gone from village to village, up and down mountains, with much artillery activity by both sides. It was clear that the Neapolitan repositories would be in the midst of any such battle and that Montevergine, which contained the Naples “A” list, was the most vulnerable of all.

This fear was exacerbated by a ferocious German propaganda campaign which predicted that the Allies would take or destroy anything they could lay hands on. In an article which is admirable for its amazing inventiveness, even in the annals of propaganda, the

Berliner Börsen Zeitung

reported:

The American wholesale art dealer Cadoorie and Company has given a commission for the purchase of Sicilian antiquities. This is the same business that made great purchases from European emigrants and arranged auction sales of paintings, furniture, porcelain and other art objects. The firm was also busy with this game in art treasures which were stolen during the Spanish civil war. Behind the name Cadoorie the Jew Pimpernell is hidden … the representative in Algiers, Sally Winestone, has arranged connections with the staff of the Anglo-American hospital ships who endeavor to carry out her commissions.

3

In late July, therefore, Bruno Molajoli, Superintendent of the Naples Museums, went to Rome to consult his superiors. It was now felt that deposits all over Italy should be removed from the vulnerable country

ricoveri

to safer spots, the safest of all, everyone felt, being the neutral Vatican, with whom negotiations for storage were immediately begun. But the Naples deposits, now closest to the battle zone, could not wait for long. In August 187 crates containing the most important things were readied for dispatch to the safest place the authorities could possibly imagine next to the Vatican: the immense monastery of Monte Cassino, remote and inviolable, at the top of a mountain fifty miles north of Naples. The precious cargo did not leave until September 6, only hours before Allied landing craft came ashore in the great assault on Salerno.

It was not until they arrived back in Naples that the curators heard the news of Badoglio’s surrender to the Anglo-Americans and realized that Italy had overnight become an occupied country in which their erstwhile allies were as much of a danger as were the forces attacking their country. The situation in Naples was terrible: in the distance could be heard the

lugubre brontolio

of artillery fire. Bombs fell intermittently on the port and the city, while in an arc around it every road, track, or convoy, and some less mundane things such as the marvelous cathedral at Benevento, just east of Montevergine, were being demolished. The Carabinieri, Italy’s national police, had been disbanded by the Germans, leaving museums and repositories without guards. Water and electricity were cut off, and all communication with the country refuges, where much still remained, became impossible.

Other books

Unknown by Nabila Anjum

The Color of Family by Patricia Jones

Angel by Phil Cummings

Crown of the Cowibbean by Mike Litwin

Legally Binding by Cleo Peitsche

Betrayed (The Worshipped Series Book 2) by Paisley, Brie

Wolf Creek Widow (Wolf Creek, Arkansas Book 4) by Penny Richards

La Regenta by Leopoldo Alas Clarin

Tycoon by Harold Robbins

The Book of Human Skin by Michelle Lovric