The Rape of Europa (52 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

By March, Mason Hammond and a number of other officers had been sent north from Italy to join in this effort, and by April the Monuments men, divided into groups responsible for planning for different countries, plus a pool of eight men who would be assigned to forward elements of each Army, were all organized. They were determined to avoid the rigid system which had been so disastrous in Italy. The “pool” officers were to be sent to whatever region or Army, British or American, needed them most. Lists and handbooks were prepared, and maps supplied to the Air Force. The long technical instructions written by Stout and Constable were boiled down into a two-sided instruction sheet.

It all seemed marvelous on paper, but in the last weeks before D-Day, reality hit. SHAEF took one look at the list of 210 protected monuments in Normandy and rejected it because there would be no place left for the billeting of troops. The Monuments men gently pointed out that many of the monuments were prehistoric stone circles and dolmens, unsuitable for residence, and at least 84 were churches. Mollified, the strategists accepted the list.

2

Much worse was the fact that the final “table of organization” for the invasion left the MFAA (Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives) section, as they were now called, out entirely, with the result that within days other parts of the Army began refusing to send them supplies or mail as they had no exact “status.”

3

This was not rectified (with many apologies, it must be said) until May 29, three days after Eisenhower had sent out an eloquent order, similar to the one issued for Italy, exhorting all commanders to “protect and respect” historical sites,

4

and a supporting

directive stating that Monuments officers should be “utilized to the best advantage in the areas for which they are responsible”—thus proving that they really did exist.

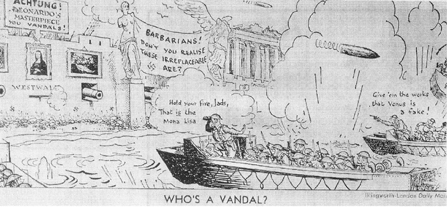

London Daily Mail

cartoon, March 1944, responding to German art destruction propaganda (Cartoon by Illingsworth ©

London Daily Mail)

The efforts of the Roberts Commission had by now also persuaded the Navy to release George Stout from a job dealing with airplane paint and had secured the services of First Lieutenant James Rorimer, former curator at the Cloisters in New York, so that the Monuments contingent now numbered seventeen. But Stout’s proposal for a mobile group of ten or so conservators had not been accepted. As it turned out, he would, for most of the campaign across France and Germany, be a group of one.

News of London developments still did not reach the Roberts Commission through official channels, but only through private letters from Woolley and his protégés in England. These friendly missives did nothing to cheer up the news-starved Commission, which was already worried by Wool-ley’s domination of the MFAA organization. They had, in fact, already begun a campaign to have an American officer of flag rank, loyal to them, assigned to England to replace Woolley in the councils of SHAEF. For this job they found a reserve brigadier general with architectural training named Henry Newton. So anxious were they to get someone overseas to compete with Woolley that they chose to keep Newton on even after his rank was reduced to colonel for the incompetence he had demonstrated while commanding an Engineer battalion in maneuvers earlier that year.

(The problem had been that Newton “did not have an Engineer company in the right place at the right time,” which had led to enormous traffic jams of tanks at a river crossing. This was to be all too characteristic of his future performance.) In a long apologia addressed to Paul Sachs, Newton dismissed his error as a “picayune” matter.

5

Sachs was still impressed by the former general and felt that “only he can speak for the General Staff and the Armed Forces

as well as for us”

and therefore coordinate the work of “our good fellows.”

Fortunately, one RC member, Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, had already been given a London mission on a State Department delegation led by then Congressman J. William Fulbright, and had gone over by air armed with a list of questions related to the status of works of art owned by private collectors. MacLeish’s mission brought him into contact with the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education, which had still not taken any very concrete steps to decide how to control movable works of art at the end of hostilities. He was now able to brief them on actions taken in the United States by the Roberts Commission.

The RC had also begun to receive copies of the Treasury reports on the intercontinental machinations of the art trade. It seemed to them that at the liberation of Europe there might be an explosion in sales of the illegally acquired objects bottled up on the Continent since the establishment of the British blockade. Such a dispersal would make recovery almost impossible. According to the 1943 declaration of the exiled governments in England, “illegally acquired objects” meant anything at all transferred in territory occupied by the Axis, even if the transaction appeared to be legal. An immediate freeze on the movement of works of art from the Continent at the moment of an Armistice was recommended by many, including Georges Wildenstein, who piously warned that a barrier should be set up against the “functioning of the diabolic plan prepared by the enemy for his profit for the post war period.”

6

In response to these fears the RC had recommended to the Treasury in February that Customs agents be instructed to hold any art objects entering the United States worth $5,000 or more, or any object of historic, scholarly, or artistic interest which was suspect, until satisfactory proof of origin was submitted. The Commission would assist in these investigations.

7

This came into force on June 8, 1944, as Treasury Decision 51072.

Shortly thereafter, the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference (known as the Bretton Woods Conference) issued an international resolution reasserting the January 1943 declaration. Furthermore, since “in anticipation of their defeat” enemy leaders were transferring assets, which included works of art, “to and through neutral countries in order to conceal them and perpetuate their influence, power and ability to plan future

aggrandizement and world domination,” the United Nations recommended that the neutral countries prevent the exploitation of these assets within their borders.

All American embassies were now ordered to gather information on the assets and activities of Axis nationals in their jurisdictions and relay it to the State Department under the code name “Safehaven.” This would be added to the data already being gathered by the economic warfare agencies of the various nations. The art market was considered an especially likely place for the concealment and international movement of assets, the theory being that Nazis could hold their ill-gotten works for some years, until public interest had subsided, and then sell them. Nobody mentioned it, but non-Nazis could, of course, do likewise.

8

All of these initiatives were now conveyed to the nine Allied Ministers of Education, who had created their own Commission for the Protection and Restitution of Cultural Material, known as the Vaucher Commission. This group envisioned nothing less than a vast pool of information listing every work thought to have been taken or illegally sold; every dealer, curator, artist, or official who might have related information; every reported victim and his location; as well as an index of places to be protected. All this would be gleaned from reports and rumors brought by refugees, spies, and Resistance groups, German press clippings, secret messages, and personal letters, and be put in useful form for a supposed postwar restitution agency—a compilation that would be an incredible task even in the computer age. In London they planned to make cross-referenced card files which would be microfilmed for distribution. Only one country was already prepared: the indefatigable Karol Estreicher of Poland had made such a list, not always accurate, based as it was on the rawest intelligence, but certainly impressive in its revelation of the massive dislocations of his nation’s patrimony.

Now more than ever, the RC felt the need for someone who would serve as liaison between the civilian committees and the Army. By late April 1944 Newton, embroiled in his rank problems and Civil Affairs Division orientation, still had not appeared. MacLeish wired back that “the British have taken over organization of the Monuments officers in this theater in consequence of the non-arrival of Newton.”

9

Newton was, in fact, about to leave. To make quite clear to the Army his duties as the RC saw them, chairman and proper lawyer David Finley wrote a long letter to General Hilldring of Civil Affairs which ended as follows:

If it is consistent with War Department policy, the Commission hopes that Colonel Newton will be in a position to carry out certain vitally important tasks which may not be strictly within the jurisdiction of

the War Department and the Theater Commanders, such as liaison work with the British and other European commissions and essential conference work with British officials and art advisors to the British Government.

10

This was a terrible mistake. Hilldring replied that Newton was authorized to do all the things mentioned in the letter

except those in the last paragraph. … As the Commission itself seems to recognize, these matters are beyond the province of both the War Department and the Theater commanders. For this reason the War Department is unable to authorize Col. Newton to take any actions in connection with the suggestions appearing in the last paragraph.

11

So it was that Newton flew off to England, arriving there on May 6, having been forbidden by his military superiors to do most of the tasks the Roberts Commission wanted him to carry out.

The unfortunate colonel, whose expectations had been inflated by the RC’s briefings and his access to the very highest circles of government while in Washington, was stunned at his reception in London. Once there, he found that there was no question of him replacing Geoffrey Webb, much less Woolley. Nor did his first encounters with the British and American officers (who had been working together for many months), during which his anti-Woolley bias was clearly expressed, endear him to anyone. Newton reported back that Woolley and the American Major General Ray W. Barker, deputy chief of planning for the invasion, who had more than a thousand officers under his command, had invited him to a meeting and noted suspiciously that they were “on excellent terms officially and personally.”

A later meeting with Woolley, Webb, and Barker he termed “largely an effort to ascertain just why and what I was doing in London … the entire two hours was spent with me parrying words and phrases … at times the silence was prolonged … but I simply let them introduce the next subject.” He was outraged when the two British officers suggested that he could be more effective in Washington, and retorted that “the War Department did not propose to have their representative 3000 miles from the scene of activity where he would be ineffectual.” Barker, whose own superior officer was British, did not like this chauvinistic attitude one bit. Pointing at Eisenhower’s office, he reminded Newton that “policies in this theater are made by the man in there and not by the War Department or the American Commission.”

12

More meetings of a similar nature with the top D-Day brass followed. By late May, Newton had raised so many hackles that Eisenhower’s Deputy Chief of Staff wrote back to the Civil Affairs Division describing him as “aggressive and full of his subject.” Hilldring of the CAD told the RC that if they wanted a representative in London they should appoint a civilian; Newton, “as a member of Eisenhower’s staff,” could not represent anyone else. A few days later Hilldring ordered Newton to “refrain from writing directly to members of the RC on all but strictly personal affairs” and to report directly to him, and he would “see to it that the Commission is kept informed by sending them appropriate extracts from your reports.”

This was not at all what the Commission had had in mind when recruiting Newton. It seemed that they were back to square one in their campaign for information.

13

It was all a comedy of misunderstanding. From their bastions in Washington both the RC and the Civil Affairs Division had a completely mistaken view of Newton’s position. Though they disagreed on his duties, they both thought of him as an important member of Eisenhower’s team. The fact was that Newton had no command powers or subordinates at all at SHAEF and was regarded by Americans and British alike only as a floating representative of the War Department authorized to report back to Washington, and someone who was not necessarily to be trusted. His outsider status was made blatantly clear by the American officer Marvin Ross, who would speak French to his British colleagues in Newton’s presence.

Other books

Charlie's Gang by Scilla James

Faking It (d-2) by Jennifer Crusie

Dad in Training by Gail Gaymer Martin

Intended Extinction by Hanks, Greg

Undaunted Love by Jennings Wright

Owned By Her Alpha: Karen (Book 1) by Sophie Sin

The Hearing by John Lescroart

Flirty by Cathryn Fox

emma_hillman_hired by emma hillman

Caught on Camera by Kim Law