The Rape of Europa (44 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

And indeed the situation outside the city was far from ideal. Cava, near the Salerno beachhead, was filled with refugees sheltering from artillery fire, and the abbot was being held hostage by the Germans. Montevergine no longer had guards and was now directly behind the German lines, although the Benedictines managed by various subterfuges to keep troops out. At the Church of San Antonio in Sorbo Serpico, one of the last refuges to be filled, the custodian refused admission to inquisitive Nazi officers, asking them to come back the next day. In the night he called together the ladies of the village, who carried seventeen large packed crates of paintings up into the hills on their backs so that the returning Germans found nothing. His caution was justified, for on September 26, soldiers enraged at Partisan resistance in Naples soaked the shelves of the University library in kerosene and set it on fire. Its fifty thousand volumes were still burning when, on September 28, the eighty thousand precious books and manuscripts from the various archives of southern Italy were discovered at Nola by foraging soldiers and, despite two days of desperate negotiations by the custodians, deliberately burned. With them also were consumed the best ceramics, glass, enamels, and ivories of the Civic Museum, and some forty-five of its paintings. These gratuitous acts of destruction

came as a total surprise to the Italians. They would have many more in the coming months.

4

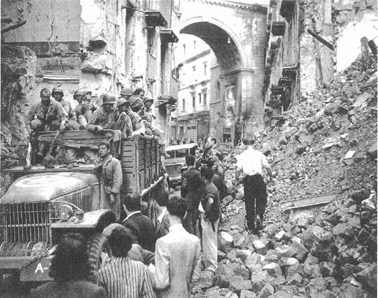

American troops enter Naples.

When, after fierce resistance by Kesselring’s forces, the Allies entered Naples on October 1, the situation did not much improve. The University now endured a second wave of destruction. Allied soldiers ransacked the laboratories, hopelessly mixing up collections of shells and stones which had taken decades to assemble. Troops soon were to be seen driving about the city in jeeps decorated with hundreds of fabulously colored stuffed toucans, parrots, eagles, and even ostriches from the zoological collection. Curators were brusquely thrown out of their offices at the Floridiana Museum. British, French, and American personnel were billeted in the Capodimonte and the Royal Palace, where, with the delighted help of Neapolitan ladies of the night, they stripped brocades from the walls, presumably to be converted into garments of one kind or another. The Museo Nazionale, where despite all the evacuations five hundred objects were still in place, was designated as a hospital-supply warehouse. Eisenhower’s aide flew in to find suitable lodgings for him near the huge Caserta

Palace (vacated by the Germans only days before), which had been chosen as the main Allied headquarters, and which housed most of the evacuated decorative arts of Naples.

5

The Italian museum authorities could find no one who seemed responsive to their protests at the use of these historic buildings. Molajoli wrote later:

The massive mechanisms of a vast army of occupation, still engaged in combat, came in contact for the first time with a great cultural center, and were faced with problems of unforeseen complexity. Despite the best intentions of the … organizations of cultural assistance set up by the United Nations … Naples had the unwanted privilege of serving as the experimental laboratory for these organizations.

6

Dr. Molajoli and his colleagues could not find anyone to deal with their problems because Major Paul Gardner, the Monuments officer assigned to the city, did not arrive in Naples for three weeks.

Efforts in Washington had produced nearly a dozen officers to join the beleaguered Hammond and progress with the armies to the mainland, but they too still languished in North Africa or Sicily. Italy was divided into fixed regions, with a Monuments officer for each one; but until an entire region was taken, the officer was not sent to the theater, even though he might have been useful in already conquered areas. Nor had the ill-fated maps ever reached anyone who could use them; in fact, the set for the Naples region had been captured when the British courier taking them to headquarters by motorcycle was intercepted by a German patrol. Monuments officers wondered for years afterward what the Germans had made of these mysterious documents.

7

On top of this, their section of headquarters remained in Sicily, split off from the rest, and totally out of contact with events.

The Monuments men were not the only ones feeling frustrated. The Roberts Commission, as the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments was now mercifully known, its chairmanship having devolved upon Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts instead of Chief Justice Stone, had finally been legitimized on August 20. But as of October 20 no official information at all on events in Sicily had reached the commission members. Despite this blackout they had forged ahead. Paul Sachs, who knew more about American museum personnel than anyone, having trained a great percentage of them, was put in charge of building up the roster of suitable officers. In the absence of information from the field, David Finley kept pressure on the War Department in a long correspondence with Assistant Secretary John McCloy, insisting that officers be assigned to tactical units and that more technical assistance be given. He wondered if the maps had ever reached air crews,

and demanded reports.

8

The commission did not know much more than it could glean from the newspapers, and the image of the United States revealed there was not much better than that of Germany when it came to the protection of monuments.

Although President Roosevelt had broadcast a message to the Pope on July 10 assuring him that the Vatican would not be a target, the first Allied bombing of Rome on July 19 made major headlines worldwide. American planes had departed, press observers on board, with adamant instructions not to bomb anything but the targeted railroad yards. Despite all precautions, bombs fell on the ancient and especially revered basilica of San Lorenzo Fuori le Mure. Axis propaganda had a field day, broadcasting a long letter supposedly written by the Pope, in which he lamented the failure of his pleas to save the city, and called upon the Allies to “reflect upon the severe judgement that future generations will pronounce.”

9

After a second raid on August 13, the Badoglio government declared Rome an open city, an act ignored by all belligerents. When he fled the capital, the Germans announced that they had “assumed protection of the Vatican,” and sealed it off with armed cordons while occupying the rest of Rome with large numbers of troops. In response, the Pope announced that he would not receive Marshal Kesselring until his troops were withdrawn from the city, and mobilized his Swiss Guard, who, armed with the latest modern weaponry but still dressed in their ancient costumes, stood eye to eye with the Germans. The standoff, vividly described by the Allied press, lasted for weeks and caused widespread consternation. “How could the Allies strike the enemy without making a battleground of the Vatican?” wondered

The New York Times.

10

A special report of destruction and German atrocities in and around Naples, brought back to Roosevelt by Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, who had just visited the battle zone, led the Roberts Commission to begin a campaign to have the Allies declare one or more of the great artistic centers of Italy open cities, to which the contents of the repositories could be taken.

11

They found little support. A confidential feeler to the Papal Nuncio was met with sympathy, but regret that “practical problems” would make such a declaration difficult: according to the Cardinal Secretary of State, “the designation of any one town or city would inevitably give rise to recriminations and complaints from other localities not thus favored.”

12

Nor was Supreme Commander Eisenhower willing to limit his tactical possibilities in any way. McCloy replied to Finley that Eisenhower “felt that while such a city could be definitely spared bombing by the American or British armies, it was not possible to guarantee in advance that the movements of the armies might not require the shelling of such a city if it

were held by the Germans and the advance of the Allied armies thereby impeded. It was his opinion that while the idea had propaganda value, it was not feasible to try to carry it out.” The Supreme Commander was not enthusiastic about placing Monuments officers with combat units either. In his view “every precaution to safeguard objects of art was being taken.” As for restoration and salvage, it was a civilian problem to be solved by the Italians, perhaps with the advice of one or two British or American experts.

13

But the prospect of civilian agencies working in the conquered areas had, by the time of the fall of Naples, died a slow and inevitable death. Obedient to FDR’s stated policy, the Civil Affairs Division had asked the Combined Command, in the midst of the Sicilian battles, when such agencies should be told they could arrive on the scene. The reply was that it was much too soon. But on August 30 Eisenhower cabled that “the present state of operations will shortly permit civilian agencies to go into Sicily.” The British, upon receipt of this message, were horrified. “The British government anticipates with considerable alarm the prospect of having thousands of starry-eyed American civilians running loose in Europe,” read one cable. They would accept only individuals who could be integrated into the Military Government structure. By November Roosevelt finally abandoned his insistence on combined civilian-military operations in the field.

14

This was a terrible blow to the Roberts Commission, civilians all, who had envisaged themselves in action on the scene, but who were thus relegated to a purely advisory role, and not even included in the distribution list for relevant military reports.

Pressure was now entirely on the Military Government to improve matters. This was not easy. The Supreme Headquarters were divided between Algiers, Naples, and the Lower Peninsula of Italy. Military Government likewise had various divisions with their own commands. On top of this an Allied Control Commission was created to deal with the Badoglio government, which also had three separate headquarters. Little wonder that no one seemed in charge.

It was only at this juncture that, on October 23, 1943, the British War Office awarded Leonard Woolley the formal title of Archaeological Adviser to the Director of Civil Affairs. On about the same date, the Roberts Commission finally received its first reports from Mason Hammond, covering events in Sicily up to the end of August. But it was not until late November that the assigned Monuments officers, waiting impatiently in Palermo, began to be placed on the mainland. Rigidly confined to their particular regions and as usual lacking transportation, they often could do little.

Meanwhile, Paul Gardner remained alone in Naples, where the administrative apparatus of the Supreme Command continued to take over the monuments of the city. The Royal Palace became an officers’ club. At Caserta the various HQs expanded geometrically to fill the two hundred rooms packed with delicate paintings and furniture which troops moved about at will. There were frequent reports of damage to Pompeii. The buildings seemed of no importance. In one of the hunting lodges at Caserta, General Eisenhower himself, instead of resorting to more conventional methods, used his pistol to kill a rat found perched on his toilet seat. (It took three shots.

15

) The medical unit assigned to the Pinacoteca, its doors generally wide open, planned to cook in the courtyard and set up cots in the galleries. There were constant complaints of rude troops breaking into locked libraries and storerooms and making off with books, coin collections, and

objets.

Woolley, who had the great advantage of being a lieutenant colonel in the British Army and high up in the War Office hierarchy, arrived on this scene on December 1. In a series of meetings at Allied headquarters, and in a stiff letter to the chief of Military Government, he pointed out the negative propaganda and political effects of the Army’s destructive activity. He mentioned that the “express desires” of the President of the United States and the British Secretary of State for War were not being observed.

The stirring up of the brass had results: a commission of inquiry was appointed to investigate the whole situation in Naples, and on December 29, 1943, Eisenhower issued to all commanders the first Allied General Order of the war on the protection of monuments:

Other books

Home to Whiskey Creek by Brenda Novak

The Blade of Shattered Hope (The 13th Reality #3) by James Dashner

Rane's Mate by Hazel Gower

Hot Match by Tierney O'Malley

Firefly Run by Milburn, Trish

The Revelations of Preston Black (Murder Ballads and Whiskey Book 3) by Miller, Jason Jack

Soul Cage by Phaedra Weldon

Clemencia by Ignacio Manuel Altamirano

Frameshift by Robert J Sawyer

The Damsel's Defiance by Meriel Fuller