The Rape of Europa (45 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Today we are fighting in a country which has contributed a great deal to our cultural inheritance, a country rich in monuments which by their creation helped and now in their old age illustrate the growth of the civilization which is ours. We are bound to respect those monuments so far as war allows.

If we have to choose between destroying a famous building and sacrificing our own men, then our men’s lives count infinitely more and the buildings must go. But the choice is not always so clear cut as that. In many cases the monuments can be spared without any detriment to operational needs. Nothing can stand against the argument of military necessity. That is an accepted principle. But the phrase “military necessity” is sometimes used where it would be more truthful to speak of military convenience or even of personal convenience. I do not want it to cloak slackness or indifference.

It is a responsibility of higher commanders to determine through

A.M.G. Officers the locations of historical monuments whether they be immediately ahead of our front lines or in areas occupied by us. This information passed to lower echelons through normal channels places the responsibility on all Commanders of complying with the spirit of this letter.

In Woolley’s somewhat optimistic words, protection now became “what it always should have been, a matter of military discipline, and as such it was cheerfully accepted by the combatant forces. The tendency to regard the Monuments officer as an interloper trying to press his own point of view against the claims of military necessity was eliminated, and he was looked upon as an adviser.”

16

The whole Monuments operation was now reorganized. Its offices were brought to Naples from Palermo, and a more flexible assignment system was approved which would allow officers to be sent forward where the need was greatest. Specific instructions were sent to lower-ranking officers, and work was immediately begun on easily distributed pocket-sized booklets listing monuments for each region to replace the excessively bulky “Harvard lists.”

Naples began to settle down. The medical unit left the Pinacoteca unscathed, and at Caserta, which remained the Allied headquarters until well after the war, the contents of the repositories were evacuated elsewhere. But Sir Brian Robertson, the British commander, would not give up the Royal Palace, in which complete cafeterias and bars had been installed. His cultural contribution was limited to an introduction to a guidebook for the edifice urging troops to “respect its age and beauty” so that future generations could “say without criticism or regret, ‘The British used this place as a club for their men when they were here.’ ”

17

At least, Woolley later wrote, “the experience of the Royal Palace at Naples was never repeated in the course of the Italian campaign … the experience was worth the price.”

18

Everyone now felt much better about the prospect of occupying Rome. The message of protection of historic buildings had been emphasized and acknowledged. Soon they would take the Eternal City and the Germans would probably give up. Allied forces had already broken through the eastern end of the enemy front, and had apparently surprised them with their amphibious landing at Anzio, actually behind the German lines, on January 22. All that now remained was to sweep forward to breach the fortified “Gustav” line centered on the ancient mountain Abbey of Monte Cassino.

Experienced as they were at setting up occupation governments, the Germans were having a much easier time than the Allies organizing themselves as rulers of truncated Italy. It was to be treated as a “Western” nation under the puppet Fascist government. This left responsibility for the incalculable art treasures of the country technically in Italian hands, but their care in the midst of battle, given Hitler’s desire to defend the entire peninsula, clearly would require the establishment of a special monuments protection organization by the German authorities. In these matters they were almost as inexperienced as their opponents, having protected nothing in the eastern battle zones, and having had little opportunity to refine battlefield techniques in the brief assault in the West. The two organizations in the vicinity concerned with such matters, a scholarly Ahnenerbe group known as the Culture Commission for South Tirol, which had been classifying “Germanic” monuments in the region, and the Kunstschutz in France, were not exactly combat-oriented.

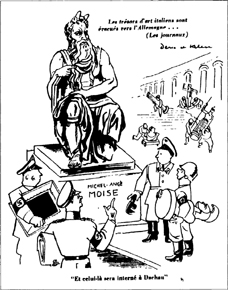

They also had a completely new problem: global public opinion. The invasion of the Italian mainland had, for the first time, exposed the Nazis on their own turf to the untrammeled democratic press. Allied newspapers carried lurid accounts of the German excesses in Naples, and were circulating equally lurid and frequently inaccurate stories about their occupation of Rome. The looting of art and plundering of churches were said to be widespread, and it was reported that truckloads of art were being removed to the north. The French

Pour la Victoire

even ran a cartoon showing Michelangelo’s

Moses

about to be transported to Dachau.

The criticism was not all from the Allied side. Birds, this time not stuffed, were also a problem for the Germans: the newly appointed ambassador to Rome, Rudolf Rahn, was shocked to see paratroops, bivouacked in the magnificent gardens of his embassy, shooting and roasting the famous white peacocks which adorned the shrubbery. His protests to the unit commander were met with some disrespect.

19

Field Marshal Kesselring was, of course, perfectly aware of the need to protect buildings and works of art. He had immediately assigned an SS officer from his Intelligence staff, a former employee of the Hertziana Library in Rome, to supervise the posting of Off Limits notices and to remove objects from combat areas to safe storage. But implementation of a coherent plan close to the constantly moving front was not easy, and the disparate units, fighting for their lives and furious at the thought of defeat, were difficult to control. Fortunately for Kesselring, the inexplicable slowdown of the Allied advance north of Naples in late October would enable him not only to create the terrible defenses of the Gustav line, but also to consolidate certain aspects of his occupation administration. For the Italian

patrimony it was none too soon. Some of the removals to “safe storage” had rather gotten out of hand.

French cartoon on the subject of Nazi evacuation of art from Italy

Despite efforts of Italian officials to stop them, thirty-nine cases of objects from the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, for years Mussolini’s residence, had been taken from a

ricovero

at Gennazaio and sent off to Milan on the excuse that they were the personal property of the Duce. Far more dramatic was the activity at the Abbey of Monte Cassino, around which frantic fortification construction was in progress. The abbey itself was not in fact technically part of the extraordinary web of redoubts, bunkers, and tunnels being prepared by German engineers, but its prominent position gazing out over the valley below guaranteed that it would become a target. On October 14 the seventy-nine-year-old abbot was visited by officers of the Hermann Goering Division, part of Kesselring’s Tenth Army. The division had recently moved its headquarters from Caserta to Spoleto. They informed the monk that the archives, treasure, and occupants of the monastery would have to be evacuated. The abbot, who feared that everything would be sent off to Germany, at first resisted, asserting that the contents of the abbey were the property of the Italian state, but in the end was forced to give in.

A team of packers was dispatched by the Goering Division to prepare the shipments, one of which would go to Rome and the other to the Division’s headquarters in Spoleto. It is not entirely clear if the German officers knew before they began packing that the Naples treasures were in the abbey, but it did not take them long to find the cases so recently moved to this refuge. Other, smaller secret caches hidden in the vast building escaped their scrutiny. Duke Filippo Caffarelli had, in December 1942, entrusted several boxes of original manuscripts from the Keats and Shelley Memorial in Rome to Father Inguanez, chief archivist of the abbey. These rested behind a secret panel in the library. No one mentioned them to the Germans and Inguanez was able to mix them in with his own personal possessions, thereby insuring that they would go to Rome and not Spoleto.

20

It took nearly three weeks to pack the contents of the monastery and transport them in multiple truck convoys down the hairpin road to the valley and on to their next shelters. Considering the precarious position of the German armies north of Naples, it was an extraordinary use of military effort.

Just who was to benefit from this remarkable altruism seemed all too clear to the Italians, who were quite aware of the tastes of the Division’s Commander in Chief. They were not only worried about the Reichsmarschall. On October 12 the Fascist Foreign Ministry had agreed with the Germans that all portable works of art should be moved from the capital to the north of Italy. This plan was diametrically opposed to the wishes of the director of fine arts, Dr. Lazzari, who had been trying since June to get the Vatican to agree to receive and store whatever elements of the Italian patrimony could be brought back from the scattered refuges which lay in the paths of the ever-advancing armies, and who, on his own responsibility, had ordered his subordinates, including those in Tuscany, to begin arranging for all the collections they guarded to be brought to Rome. On November 2 the Vatican finally agreed to receive the Italian treasures.

Lazzari drew support for these efforts from an unexpected quarter: a group of well-known German intellectuals and diplomats based in Rome and Florence. Their concern was not entirely disinterested. The two cities had for centuries been the meccas of serious students of art history, and for Germans more than any others, they being generally credited with having invented this discipline. They had four major establishments in Italy: the German Archaeological Institute, the Hertziana Library, the German Historical Institute in Rome, and the German Art Institute in Florence. The directors and employees of these world-renowned centers had been ordered to leave Italy along with other German nationals in the panic following Badoglio’s armistice.

The Roman groups in particular had planned ahead. Only days after Mussolini’s fall Professor Bruhns of the Hertziana secretly asked his colleague, Dr. Sjoqvist of the Swedish Institute of Classical Studies, if he would protect the Hertziana from both the Allies and the Italians. When Sjoqvist suggested that the Vatican would be the best protector, Bruhns replied that the Holy See could only be approached through diplomatic channels, and that this would be considered high treason as it would reveal “distrust in the final victory.” He would, however, try to appeal to certain Cardinals in the Vatican. Bruhns was followed in short order by Professor von Gerkan of the Archaeological Institute, who was both anti-Nazi and anti-Italian, and who also handed Sjoqvist an official letter making him responsible for his institute.

These actions were condoned by the German ambassador to the Vatican, Baron von Weizsäcker, who obtained assurances, reportedly from the Pope himself, that the Vatican would protect the libraries if necessary. The offer naturally had to be publicly rejected as “incompatible with the Reich’s dignity,” but the precedent of Vatican refuge had been established and certain attitudes revealed. The same Germans who wished to have the German institutes moved there also favored this refuge for the Italian patrimony. They were tacitly supported by Ambassador Rahn and the German consuls in Rome and Florence.

21

Other books

Tom Paine Maru - Special Author's Edition by L. Neil Smith

Bark (The Werewolf Journal's Book 1) by Sabian Masters

Midnight Pass: A Lew Fonesca Novel (Lew Fonesca Novels) by Stuart M. Kaminsky

Soulstice (The Souled Series) by Murdock, Diana

About That Night by Julie James

Spake As a Dragon by Larry Edward Hunt

Taken Love by KC Royale

Reckless Runaway at the Racecourse by Ros Clarke

Meet Me at Midnight by Suzanne Enoch

End of the Innocence by John Goode