The Rape of Europa (70 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

It was clear to all that a great deal more storage space would be needed. On the following day, LaFarge and Rorimer went to Wiesbaden and managed to secure another large building, the Landesmuseum, the former bailiwick of Linz chief Voss, as their third Collecting Point.

Reception of the withdrawal directive accelerated the already feverish pace of the field operatives. George Stout, who had gone up to Alt Aussee on June 15 with his famous sheepskin coats to begin the six-week evacuation process, did not at first know of the Presidential directive. He managed to get off one convoy on June 16, but his whole careful plan was upset by the sudden removal of transport and the additional officers he had been promised. As there was still no telephone communication with Third Army, he went to Salzburg to phone Posey, and the reason for the schedule changes was soon explained.

Stout, who had been joined by his new assistant Thomas Carr Howe (director of the San Francisco Legion of Honor Museum) and Lamont Moore, was racing against time. On June 24 he “arranged to go on longer day 0400–2000.” The logistics were exhausting. He was responsible not only for the moving and packing of the mass of objects but also for the care and feeding of the drivers, loaders, and guards; the organization of the convoys; and the rescue of trucks that broke down in remote places. Night

and day the MFAA men and the mine staff still dressed in their distinctive, button-covered white uniforms, rode back and forth in the shadowy chambers on the miniature trains. Innumerable truckloads wound down the precipitous roads to Munich, 150 miles distant. It rained and rained. Food was scarce; “All hands grumbling,” Stout wrote.

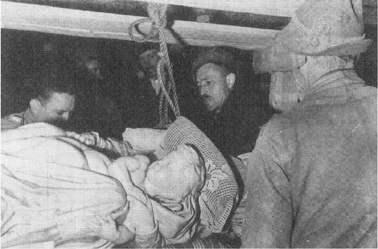

Alt Aussee: George Stout supervises removal of the Bruges

Madonna;

note mattresses and lace-curtain packing material.

When packing materials ran out they sent loads of tapestries instead of pictures while they waited for the sheepskin coats, crates, and excelsior to be recycled after the objects had been unpacked in Munich. Perfectionist Stout would not release anything that was not properly packed, and the convoys were so unreliable that by the July 1 deadline the Belgian masterpieces still had not been moved. But there having been no settlement of the issue of the Austrian boundaries by that date, the evacuation continued on into July. By the nineteenth, one month after the Alt Aussee team had started, they had moved eighty truckloads which had contained 1,850 unpacked paintings, 1,441 cases full of others, 11 large sculptures, 30 pieces of furniture, and 34 large packages of textiles—and this still left a large amount for the next generation of Monuments officers. Exhausted, George Stout left for Paris and home on July 29, having spent just over a year in Europe. He had taken one and a half days off.

The British, though not in agreement with the American policy,

nonetheless cooperated in this operation. At Schönebeck, one of the Berlin repositories, the Americans had in the first days of liberation taken only large quantities of documents relating to the giant Siemens industries, and not the art, before handing the area over to the British. Nearby the barges sent from Berlin by museum director Unverzagt had, since April, remained half unloaded at their quay, the rest of their cargo stacked up outside the mine. In the last three days before Schönebeck was left to the Soviets, the British moved all this, along with reams of archives, to a temporary Collecting Point in the former Imperial Palace at Goslar, well within their Zone.

British Monuments officer Felix Harbord, not entirely immune to the fact that the Duke of Brunswick was related to the British Royal Family, also undertook the evacuation of the ducal schloss of Blankenburg. Here, the local Provincial Conservator, Karl Seeleke, had, with considerable bravery and the help of the entire town, including the sons of the Duke, stored the treasures of Brunswick. This operation, begun June 25, Harbord managed to continue until July 23, moving his cargo to Goslar on ever-varying routes through the Harz Mountains in relays of thirty British Army trucks escorted by three armored cars until the Red Army had secured the last road.

9

Those on the receiving end of these massive transfers worked just as hard as their mobile colleagues. The day before the first convoy was to arrive at the Munich Collecting Point the situation there was still terrible. Although a weatherproof room was ready and a registration system for incoming works had been devised, there was no steady guard unit assigned. The neighboring Führerbau had been broken into, the communicating tunnels were far from secure, and there still was no fence—there was not even a telephone. Half the picture handlers had been rejected as Nazis, and others, probably equally suspect, had quickly been hired from a Munich moving firm. Five hours before the trucks were due in, the guard detachment announced that it was leaving and would be replaced by another, which of course would not be familiar with the building. Lieutenant Smyth was forced to go in person to headquarters to fight for a guard battalion for that night.

On June 17 the first major delivery arrived from Alt Aussee: eight trucks containing large numbers of top ERR pictures. By late July, Smyth would be responsible for 6,022 “items,” many of them cases with multiple contents, so that the actual total was far higher. Among them were the Altdorfer altar from St. Florian, the Belgian treasures, the Monte Cassino pictures, the cream of the Budapest Museum, the Czernin Vermeer, the

Rothschild Vermeer and their jewels, an ancient primitive statue from Saloniki, most of Goering’s collection, and far more. Fortunately the barbed-wire fence had finally been put up, and the staff had been expanded to cope with the deluge. In the front office a secretarial pool of judiciously chosen but good-looking young German baronesses and other well-born ladies typed away—an arrangement criticized by the humorless Posey as inappropriate. But the security of the building was still marginal, the only fire protection was that which could be provided by the war-torn city, and many rooms were not yet weatherproof. There were more dramatic problems: despite sweeps by bomb experts an explosion on July 20 killed a sixteen-year-old worker and blew out all the power in the Collecting Point.

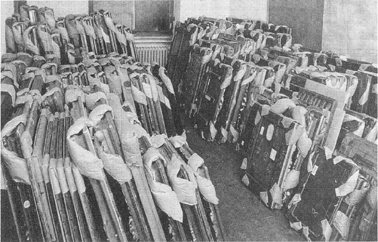

A curator’s nightmare: one of the crowded storage rooms at the newly opened Central Collecting Point in Munich

This episode unfortunately occurred two hours after the arrival of Bancel LaFarge and John Walker, who had come to view the repositories for the Roberts Commission. Walker found “everything perfectly arranged and functioning beautifully,” but noted that the “building was shaken” and “bomb disposal squads are going to search for the fifth time for booby traps.” When Smyth took him on a tour of Hitler’s quarters Walker thought it interesting “not only because of its bad taste, its bar, which had pornographic murals [Ziegler’s] … its Pullman style furniture … but also because of a childish love of secret passages … leading from one building to another and even under the square in front.”

10

The visitors discussed various problems with Smyth, including the possibility of heating the Collecting Point during the coming winter. It was far from a sure thing. Smyth wrote: “If not, job easy. If so, need more officers, preferably supply or engineering to help. If not, can have jury-rig—not elaborate, absolutely simple. If so, must be conceived in more permanent terms because of necessity of rebuilding for insulation.” Later there arose the question of where the coal for heating would come from. “Reply: Group CC would have to decide and furnish. Question: how to proceed at present. Reply: proceed as if Galleries were to be heated.”

11

A bit later Smyth told his staff only that they would be able to keep the gallery “a little above freezing.” Group CC was General Clay’s turf. And Clay was at the Potsdam Conference at that very moment, trying to get a clear mandate for the running of the American share of the shattered German nation.

The Wiesbaden Collecting Point was still in an embryonic stage. Experience at Munich had shown that architectural training, at least at the beginning, was just as important as museology. And the three-hundred-room Landesmuseum certainly needed someone who could make it habitable in the shortest possible time. Fortune brought the MFAA another exceptionally dedicated officer in the person of Captain Walter Farmer, an engineer with architectural and interior design experience. Farmer, longing to be released from his unit—which was engaged in the dreary business of building POW cages—had offered his services to the MFAA office at SHAEF and was immediately accepted. He was ordered to take over on July 1 and to have the Collecting Point ready by August 20. This was an eon compared to the two weeks granted Smyth, but still not very long.

The Landesmuseum was not in any better shape than the Munich buildings had been. One large area had been occupied by a Luftwaffe machine shop, and the remains of five antiaircraft gun emplacements graced the roof. U.S. Twelfth Army had a clothing depot in the art galleries; the Rationing Office was in Archaeology. DP families lived in every other viable space. There were no unbroken windows at all, and the heating had not been used for years. Farmer’s first act was to make the perimeter secure. He was assigned a labor force of 150 German sappers, still in their uniforms, who began putting up fences and floodlights. To find out where building materials might be hidden, he ordered a meeting of local contractors in the movie theater.

Soon the museum’s windows were glazed, tons of rubble and flak fragments were cleared from the roofs, and interior doors, 90 percent of which had been blown off their hinges, were rehung. Most miraculous of all, the heating system was coaxed into operation; the proper humidity so vital to panel paintings was provided by putting wet blankets in the air ducts and

keeping certain areas of the floors wet. Staff was hired and plenty of art historical advice was forthcoming to Farmer from other MFAA officers working in Frankfurt. One such was Edith Standen, a WAC captain and former curator of the Widener Collection who had been assigned the immense and tedious job of inventorying the artistic contents of the Reichsbank in Frankfurt in preparation for its move to Wiesbaden. (Hers was musty and exhausting work. The crates, Nationalgalerie pictures, and golden Polish church treasures were one thing, the two-foot-high stacks of rugs and charred archives quite something else.)

By late July, Farmer, exhilarated by his job, wrote with some understatement that “everything necessary has been obtained by one means or another.” His confidence was fortunate, for he was about to be given responsibility for the entire assemblage of works of art evacuated from Berlin, plus much more. It was, as Smyth had found in Munich, not easy. Farmer too had his problems when it came to security. Noting that he “hated to make money estimates, but the average American demands it,” he casually mentioned to the local commander that the incoming works were worth more than $50 million. This made such an impression that he was given extra guards. He needed them. In the first week the Collecting Point was open, fifty-two truckloads, impressively escorted by tanks, arrived. And they kept coming: “Three more truckloads of prints yesterday, and Thursday two truckloads of gold and church ornaments and a bit later six truckloads of paintings etc.,” Farmer reported. There were no hours left for unpacking the objects or contemplation. Even the famous head of

Nefertiti

, which Farmer was especially proud to be guarding, would have to wait until 1946 to be viewed.

12

In late August the British too transferred most of their holdings to a permanent Collecting Point in a vast schloss at Celle, thirty miles northwest of Brunswick. Here were taken objects from the Berlin collections, found in the mines which had come under British jurisdiction. From Schönebeck and Grasleben, which had been looted and where a fire that had started in the film archives had burned for days and caused extensive damage, the objects arrived in terrible confusion and poor condition. Director Harbord, more interested in reviving theater and putting on exhibitions, left administration of the Collecting Point entirely to a German dealer and collector named E. J. Otto who had volunteered his services. Harbord’s successors were not much more enthusiastic about the tedious processes of opening and checking the contents of the thousands of crates of German-owned objects at Celle which contained, among other things, the priceless Gans collection of Roman gold objects.

Other books

Thunderland by Brandon Massey

Dark Legion by Paul Kleynhans

The Claiming of Zoe (Supernatural Strippers Series) by Browning, Amanda R.

Custody by Manju Kapur

A Deeper Love Inside by Sister Souljah

Either the Beginning or the End of the World by Terry Farish

Poirot investiga by Agatha Christie

Quag Keep by Andre Norton

WereCat Fever by Eliza March

Cats Triumphant by Jody Lynn Nye