The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (47 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Before leaving this web of tenuous linguistic clues to Scandinavian influence on Old English, I should, at least speculatively and anecdotally, mention an internationally recognized modern English dialect known as Lowland Scots or Lallans, which seems to have retained more Norse and Common Teutonic vocabulary than has English farther south. For examples, a few words I jotted down on an envelope before checking in the

OED

include

bairn

(‘child’),

burn

(‘stream’),

ken

(‘know’ or ‘suspect’) and

kirk

(‘church’).

17

Lallans is Germanic, is distinct from Scottish Gaelic, and is attested back to Late Medieval times. Northumbrian Middle English is thought to have strongly influenced Lallans. That may be so, but that would not explain the Norse vocabulary, given the conventional view that Northumbrian Anglian was supposed to be West Germanic. Viking influence has also been suggested.

I also wonder about the linguistic affiliations of the mysterious ‘other’ Pictish language referred to by Kenneth Jackson

as non-celtic (see

Chapter 2

). As mentioned earlier, Adamnam said at the end of the seventh century that St Columba, a

Gaelic-

speaker, had used an interpreter to converse with the Picts in the previous century.

18

This-may have meant that they spoke a non-celtic tongue. Picts were still apparently a vigorous nation during the eighth century, in Northumbrian Bede’s time. Apparently, the Picts did not speak a language Bede recognized, celtic or Anglian. Was this the ‘non-celtic Pictish’ Jackson refers to? Bede, being Anglian, ought to have been able to identify a Germanic tongue. Pictish seems to have disappeared without trace in the past thousand years. Could it have a substratum in modern Scottish dialects? Whatever its origins, the written evidence for Lallans goes back no further than the Late Medieval period, so cannot form the basis for more than speculation.

But surely, if there had been previous Norse invasions and/or there were pre-existing Germanic-speaking communities living in England before Gildas’ three longboats arrived, there should be some record of this, in ancient texts or inscriptions or place-names? As it happens, there are several records of foreign and even Saxon presence in Britain during the Roman period. These can be found in contemporary Roman texts, and later confirmed by Bede. And there is other evidence too. Some of it is archaeological and, depending on historic preconceptions, may be less obvious and more contentious. We now move into this literary and archaeological minefield.

ERE THERE

S

AXONS IN

E

NGLAND BEFORE THE

R

OMANS LEFT

?

By the third century

AD

, the regular Roman army was partly Germanized. Any archaeological evidence for a Saxon presence in England in Roman times has usually been put down to mercenaries or legionaries from across the North Sea, the so-called

foederati

, but there are other interpretations.

1

The Venerable Bede, for instance, tells us about much earlier ‘infestations’ by presumably Germanic-speaking Franks and Saxons in his

Ecclesiastical History

:

In the year of our Lord’s incarnation 286, Diocletian, the thirty-third from Augustus, and chosen emperor by the army, reigned twenty years, and created Maximian, surnamed Herculius, his

colleague in the empire. In their time, one Carausius, of very mean birth, but an expert and able soldier, being appointed to guard the sea-coasts, then infested by the Franks and Saxons, acted more to the prejudice than to the advantage of the commonwealth; and from his not restoring to its owners the booty taken from the robbers, but keeping all to himself, it was suspected that by intentional neglect he suffered the enemy to infest the frontiers. Hearing, therefore, that an order was sent by Maximian that he should be put to death, took upon him the imperial robes, and possessed himself of Britain, and having most valiantly retained it for the space of seven years, he was at length put to death by the treachery of his associate, Allectus. The usurper, having thus got the island from Carausius, held it three years, and was then vanquished by Asclepiodotus, the captain of the Praetorian bands, who thus at the end of ten years restored Britain to the Roman empire.

2

For this part of his text, Bede, by nature a careful historian, was not obliged to repeat wild harangues about fifth-century Britain garnered from the prophet St Gildas, but comfortably used more reliable texts. But it is not clear here whether the infestation of Saxons and Franks meant unwelcome mobile parasitic residence or overseas invaders, nor which coasts they were infesting and attacking.

To do him justice, Carausius may have been forced into rebelling by the accusation of corruption. Carausius belonged to the Menapii, one of the Germanic tribes in the far north of Belgic Gaul in Holland, just south of the Rhine, who gave Caesar so much trouble (

Figure 2.1a

). He operated out of Boulogne. What seems extraordinary is that, as a ‘non-Celtic’ usurper, he found it so easy to move across the Channel and then dominate Britain

for seven years – unless he already had very good contacts on the other side.

Bede’s text suggests that for a short time in Roman Britain of the third century

AD

there may well have been a Germanic ascendancy as well as a chronic Germanic ‘infestation’ in southern England, and that only the return of the Romans prevented the retreating Franks from sacking London.

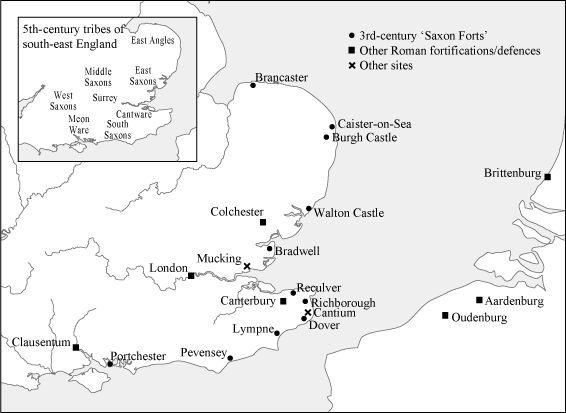

During his short rule of Britain and northern Gaul, Carausius is credited variously with building, starting, or at least continuing a network of huge forts or walled enclosures along the so-called Saxon shore. Parts of these buildings can still be seen today (

Figure 9.1

). There are eleven or twelve of them strung along a stretch of coast from Brancaster (Branodunum) in Norfolk, round East Anglia, Essex, the Thames Estuary and Kent, to Portchester (Portus Adurni) in Wessex, opposite the Isle of Wight. Although extensively reconstructed in Medieval times, the Portchester fort forms a huge enclosure and is regarded as one of the finest Roman monuments in Europe.

3

The popular English TV archaeologist Francis Pryor has questioned the orthodox assumption that these enclosures were necessarily all forts, let alone part of a system of defence against attacking Saxon pirates, and suggested that they were probably fortified trading or distribution stations. In his recent book

Britain AD

, he spends a whole chapter arguing that the semantic embellishment of the

anti

-Saxon fort system is part of millennial, circular, self-fulfilling mindset of ‘proofs’ used to support the original Gildas Saxon blitzkrieg story.

Figure 9.1

Forts of the Saxon shore. Listed in a late Roman military inventory as under the command of the ‘Count of the Saxon shore along Britain’, these were probably fortified trading stations rather than defence against Saxon pirates. As such, they described the distribution of fifth-century Saxons (inset) rather well, thus suggesting the Saxons were already in residence in Roman Britain.

The name ‘Saxon shore’ first appeared in a late fourth-century Roman military inventory, the

Notitia dignitatum

(‘Register of Offices’), as

Litus Saxonicum.

In this document, various military buildings on both sides of the English Channel were listed as ‘under the command’ of the ‘Count of the Saxon Shore’. Pryor points out that ‘just because the forts were listed under the same heading in the

Notitia,

it does not mean that they were part of an integrated system of coastal defences across the Channel, as has been suggested’.

4

He continues:

The strangest aspect of the ‘Saxon Shore’ forts is the paucity of archaeological remains across their interiors … the Romano-British

[occupation] in the third century … was not at all what was expected: there were no barrack blocks, granaries or headquarters buildings … within the massive walls … [O]ne would doubt whether Portchester was even a military site. It seemed to have most of the hallmarks of a civilian settlement, and not a very organized one at that.

5

Pryor also repeats another archaeologist’s views (Andrew Pearson,

6

with whom he agrees), that the location of the three earliest ‘forts’ ‘makes no military sense, because they would have left Suffolk, Essex, southern Kent, Sussex and Hampshire undefended’. And ‘at least half of the “Saxon Shore” forts were abandoned before the end of Roman rule, at precisely the time when Gildas and Bede tell us that Saxon raids were becoming a problem.’

7

Instead of trying to make military sense of forts built at the wrong time in the wrong place for defence, Pryor turns the problem round and asks what purpose these bases actually served. He provides an answer by building up a picture of these ‘forts’ as ‘part of long-distance trading networks … in effect secure stores’

8

– a view which much better fits their locations. Pryor summarizes his perspective on the defence question:

Gildas greatly exaggerated the severity of Anglo-Saxon piracy, which mainly seems to have been confined to Gaul and the southern side of the English Channel. Far from being cut off from the Continent, Britain would appear to be actively trading overseas throughout the fourth century, and perhaps later.

9

So, apparently there was not much need for defence during the fourth century against marauding ‘Saxons’ on our side of the Channel. Elsewhere Pryor points out that ‘The

Notitia

…

does not provide us with grounds to suppose that British “Saxon shore” forts had counterparts in Gaul, and formed part of a cross-Channel system of defence …’

10

To my mind, Pryor just misses tackling the key semantic question head on, although it is implicit in his whole discussion. The question is this: why, if the ‘forts’ were nothing more than a chain of bonded warehouses, tax-collection points, or whatever, were they called ‘Saxon’, and what did ‘Saxon shore’ actually mean? In other words, who and where were the Saxons of the Saxon shore? The only thing we can be sure of is that the fourth-century Roman clerks who compiled the

Notitia dignitatum

referred to a group of enclosed, fortified buildings along the coasts of Essex, Sussex and Wessex as under the command of

comes litoris Saxonici

– ‘Count of the Saxon Shore’. The meaning of ‘Saxon’ remains ambiguous in this title, mainly because of Bede’s text (above), written hundreds of years later, which was clearly influenced by Gildas. Three interpretations have been suggested: it could mean ‘the coast defended

against

the Saxons’, or ‘the coast defended

by

the Saxons’, or ‘the coast

settled

by the Saxons’. Only one of these interpretations casts such coastal Saxons as invaders. The simplest translation of the full Latin military title,

comes litoris Saxonici per Britannias

– without the Gildas/Bede spin – is ‘Count/Companion of the Saxon Coast along Britain’.

11

If a few Saxon pirates were not perceived as sufficient threat to build proper defence forts in the fourth century, why should the Romans have named the busiest trading coast of Britain, fronting a quarter of the island, after a few pirates, rather than

after the current local inhabitants of that coast? Given the lack of other reliable context, the view of Saxons as already settled on the ‘Saxon coast’ of south-east England during Roman times seems another reasonable inference.

Several hundred years later, the inhabitants of the ‘Saxon shore’ were still known as East Saxons, South Saxons and West Saxons. Given our complete reliance on Gildas for the intervening period, and his lack of dates or useful context, the coincidence seems remarkable. The only named non-Saxons in this region were the inhabitants of Kent. Kentish people, supposedly derived from Jutes and Britons, spoke a dialect of Old English heavily influenced by Norse. The post-Roman self-identified name of the men of Kent, ‘Ceint’, is argued to be a Jutish version of the original Romano-British Cantiaci of Cantium (‘Cantia’ in Bede). Authorities differ on the derivation of the original Roman place-name ‘Cantium’, but one point on which they all agree is that some version of the root

Cant

- was already old, even in Roman times, since Pytheas and Diodorus used it.

12

Ptolemy’s

Kantion

promontory in Kent is regarded as one of the ‘Harder ?British’ place names to identify etymologically in the recent analysis of Ptolemy’s map (

Figure 7.2

) of Britain.

13

Jute is cognate with Jutland, part of modern Denmark. Why the new Jutish overlords should hang on to an old, possibly immigrant name as their tribal designation is not clear. Caesar clearly regarded the Cantiaci as non-aboriginal, although whether they were Belgic/Germanic-speaking or Gaulish-speaking he did not say (see above).