The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (22 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

It is tempting to wonder whether this cold snap put the burgeoning recol onization of Britain back to the Ice Age, with Northern Europe depopulated and our ancestors scurrying back south to their refuges. This is an important question. However, there are several pieces of evidence to suggest that our hunters were just as hardy as the polar wild flowers and hung on in there, albeit in lower numbers, in all the places they had reoccupied. There is archaeological evidence for continued human activity in Northern Europe and Britain throughout the Younger Dryas.

67

In Britain there are bone, antler and ivory artefacts from the Younger Dryas, although there is a gap in the record of more elusive evidence for actual human remains and butchered animal bones.

68

In any case, the vegetation in north-west Europe did not revert to polar desert, remaining as steppe tundra. This is an environment modern humans tolerated in a number of other places such as the northern Ukraine all the way through the LGM.

69

Situated on the edge of the continental shelf, Britain may even have had more temperate and less extreme weather

– as is the case today. There is also the dated and quantified genetic evidence, already discussed and based on today’s populations, which suggests that a major north-westward European expansion of mtDNA- and Y-gene groups preceded the Younger Dryas.

70

Several of the founding Y clusters dating to

before

the Younger Dryas, such as Rory, are unique to the British Isles and so could not have ‘recolonized’ from somewhere else

after

it.

The Younger Dryas finished even faster than it started, perhaps over a period of just fifty years. Effectively this was the end of the last ice age; it would not get as cold again, except for a minor freeze-up around 8,500 years ago.

71

In ‘uncalibrated’ radiocarbon years, the warm-up comes out as 10,000 years ago. The last 10,000 years of our modern post-Ice-Age (also known as Post-Glacial) era is also conventionally known as the

Holocene

epoch (meaning roughly ‘completely new’) to differentiate it from the preceding nearly two million years of the

Pleistocene

(or Great Ice Age). However, in spite of this apparent agreement of radiocarbon dating and geological era, the dramatic warm-up after the Younger Dryas actually happened around 11,500

calendar

or

corrected

years ago, not 10,000.

The Holocene was indeed something completely different. Its onset changed the hunting landscape for ever and took European human culture into the Mesolithic. The vast Subarctic steppe habitat known as the Palaearctic Biome simply disappeared from the northern hemisphere, and large, cold-adapted beasts such as the mammoth, woolly rhinoceros and giant deer vanished eventually with it. Much controversy rests on whether human hunters or the changing weather (or perhaps both) were responsible for the loss of mammoths in Europe.

72

However, an increase in the incidence of mammoth remains from the time of

maximum hunting by humans, just before the Younger Dryas, rather goes against our ancestors having had a primary role in the extinction, at least in Europe.

73

After the Younger Dryas, most of the Palaeolithic hunters’ rich, chilly grasslands disappeared, along with the mammoth’s habitat, to be replaced by woodland. Other herds, of elk and reindeer for example, moved farther north, to be replaced in the south by wild pig, red and roe deer, aurochs and a variety of smaller mammals.

There was much ice left to melt down, apart from the vast sheet over Scandinavia, but it did not melt gradually. Immediately after the Younger Dryas, sea levels rose at a dramatic rate, which eventually slowed until another warm-up hit and produced the highest post-LGM temperatures, causing the final over-topping ‘flood’ of the Black Sea around 7,500 years ago.

74

Now, let us see what our ancestors were doing in this post-glacial springtime, also known as the Mesolithic.

LTIMATE HUNTERS AND GATHERERS: THE

M

ESOLITHIC

The cultural period following the Younger Dryas Event, the Mesolithic, saw the final and most sophisticated flourishing of the hunter-gatherer lifestyle in Europe. It was the golden age of coastal hunter-gatherers. The Mesolithic was a time of rapid innovation in stone tools and increasing use of microliths – very small, multipurpose stone tools which had already been in use in Africa and India for 20,000 years – and preceded the Neolithic agricultural revolution. Quite a bit is known about how Mesolithic hunter-gatherers lived, and one major feature in the evolution of their lifestyle in north-west Europe was a reduction in big game hunting and an increasing reliance on the beach and sea. In making this change, our Mesolithic ancestors resembled their African forebears, who were the first humans

to see the great advantages of seafood,

1

but the reason for the change in Europe was the encroachment of the forest, not the desert.

In terms of stone tool technology in the Early Mesolithic, some has been found in Uxbridge, Middlesex, and in Suffolk, where there was a short-term carry-over of tool types similar to those from before the Younger Dryas, and to those found in Germany. This would be consistent with continuous occupation of Britain throughout that cold period.

2

Perhaps the best-preserved and researched record of Mesolithic life on the north-west European plain comes from Denmark, which in spite of rapidly rising sea levels (

Figure 4.1

),

3

was then still connected to England across the southern North Sea Plain (

Figure 4.2

). Archaeologists recognize three phases in the Danish Mesolithic, recording a relative decrease in the availability of larger game as the forest became denser, and an increase in coastal settlements and reliance on fishing and beachcombing. Conditions for the preservation of vegetable matter vary from one site to another. But the best-preserved artefacts are beautifully fashioned bone fishhooks, carved painted wooden paddles, neatly made wickerwork fish-traps, spears, bows and arrows, ropes, woven textiles and even log-boats. These give us a unique window onto the more perishable aspects of the lifestyle of fishing folk and hunter-gatherers of the north-west European plain.

4

North of the rapidly shrinking plain, east coastal Scotland shows similar Mesolithic settlements around the Tweed and Forth river estuaries.

5

On the west coast of Scotland, archaeologists have reconstructed a detailed picture of Mesolithic folk angling for fish such as saithe (a species of pollock) all year round on Oronsay Island, off Jura, and raising huge shell middens with at least seven species of shellfish. In other places, such as the Island of Risga at the mouth of Loch Sunart in Argyllshire, the pickings were even richer. In addition to the usual shellfish, nine fish species of varying size, eleven species of water birds – including the great auk, gannets and geese – two seal species, not to mention red deer and wild pig, all came to the hunter’s table, along with more than just two vegetables.

6

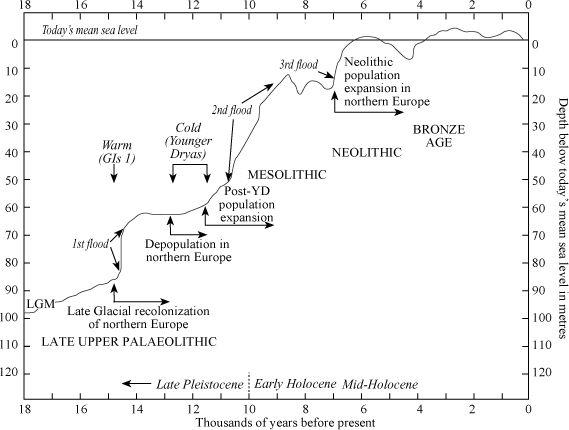

Figure 4.1

Sea-level rise after the last Ice Age. This graph shows mean world sea-level rises since the last Ice Age. These took place in a series of three dramatic warming and flooding episodes during the Late Glacial, Post-Glacial, post-Younger Dryas and Early Neolithic periods, separated by cold periods, such as the Younger Dryas Event. The three warm, flooding periods correspond to three recognized periods of human cultural and geographical expansion into northern Europe: Late Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic.

Ireland was no exception to the trend towards coastal and river-based subsistence, with Early Mesolithic settlements along the coast in the north-west and up the estuary of the River Bann. Large wooden buildings up to six metres in diameter imply an increase in communal settlement. Later in the Mesolithic, as Ireland separated from Britain, there was a change in stone tools from microliths to flint blades, and more reliance was placed on beachcombing, as reflected by huge shell middens, for instance in Sutton and in Dalkey Island, in Co. Dublin. On the Dingle Peninsula in the south-west, this lifestyle continued in pockets long into the Neolithic period.

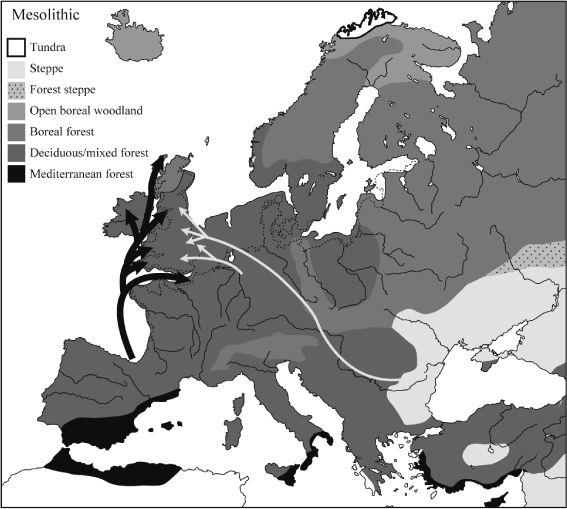

Figure 4.2

Mesolithic colonization of north-west Europe. Extensive forest cover during the Mesolithic reduced grassland hunting and forced increased coastal exploitation. The Balkan and Iberian refuges both acted as gene pools for re-expansion after the Younger Dryas, leading to two different sources of gene flow into Central Europe, while the British Isles still received the bulk from the south-west.

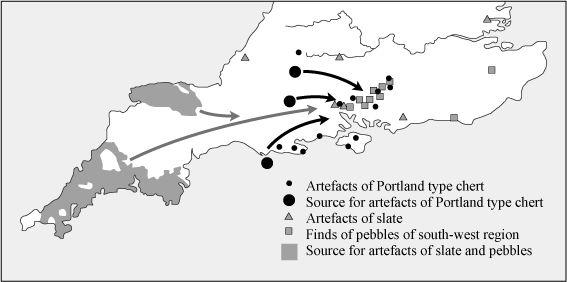

However, the greatest density of settlements in the extended Mesolithic continental shelf of ‘Greatest Britain’ was in the south of England, where the emergence of two distinct territories with different resources was already apparent. In the south-west (Cornwall, Devon and Dorset) there were mainly stable coastal settlements, that sustained themselves by both beachcombing and hunting small mammals in the hinterland, much the same as in north coastal Ireland. The south-eastern territory was around the Isle of Wight (which was no island then) and its hinterland. Trade in prized stone materials thrived between the two regions (

Figure 4.3

).

Somewhat similar coastal Mesolithic settlements can be traced down through Brittany to Spain and Portugal. One would like to know what regional connections these Atlantic coastal cultures may have had with one another, either of a cultural nature or in terms of northerly migration. Barry Cunliffe examined cultural connections in his excellent book on this region and found some evidence of unity in their culturally and technologically innovative lifestyles. But these links were nothing in comparison to the trans-continental cultural trails of the Neolithic period and later. For instance, Cunliffe mentions the similarities between harpoon points found in Spain and on the western Scottish coast – only to dismiss this as serious evidence of migration. Although there is clear evidence of trade along the south coast of England, technical styles of tool-making vary from location to location in north-west Europe, suggesting that communities were beginning to settle down and create individual cultural identities. This would be the first stage in a process that would exclusively and visibly link such identities to territories.

7