The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (48 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Pryor sees Anglo-Saxon communities as already present in the southern English archaeological record of Roman times, and points, for instance, to the Saxon site of Mucking in Essex,

where Late Roman bronzes are found in both Saxon graves and Saxon huts dated to around

AD

400. He argues strongly against the standard rationalization that these were just random homes of immigrant Germanic mercenaries, the

foederati

. I shall come back to the archaeology of the transition later; but returning to the question of identity and timelines, it is worth examining several consistent differences between Gildas and Bede’s ‘rendering of Gildas’, which are revealing as to how recently the Saxons had immigrated and who Bede’s ‘Britons’ and ‘English’ really were.

Gildas identifies the occupants of the three invited warships as Saxons, who first landed on the eastern side of the island to help fight the Picts and the Scots.

Bede, although clearly trying to follow what he has read in Gildas, introduces a note of doubt in his transcription in chapter 15, book 1 of the

Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation

. He writes ‘Angles or Saxons’ (

Anglorum sive Saxonum

), as if to question Gildas’ identification of the Saxons as the invitees-turned-invaders. In fact, Bede’s title for this chapter refers only to

Angle

invitees, which would seem more appropriate, since the eastern side of England was indeed where we find them in ‘Anglo-Saxon’ times. This is one of several places where Bede seems implicitly to doubt Gildas’ accuracy, without saying so explicitly. What grounds he had in this instance we may never know, but there are clues elsewhere in Bede’s text. Again, at the end of the previous chapter, Bede repeats Gildas’ tale of

King Vortigern’s invitation to the Saxons as ‘

Saxonum gentem de transmarinis partibus in auxilium vocarent

’ (i.e. to those Saxons who lived overseas), thus not specifying whether the general designation ‘Saxon’ meant Saxons living in Europe or included others

in Britain

at the time of Vortigern.

Later, in chapter 16 Bede repeats Gildas’ description of the famous fifth-century battle of Badon Hill, where Britons led by Roman citizen Ambrosius Aurelius – of royal descent, and thought by some to be King Arthur – defeated their enemies. However, where Gildas identifies the battle as taking place forty-four years and one month after the Saxon landing, and thus presumably with Saxons as the enemies, Bede identifies Angles as those invaders of forty-four years before and the enemy in the siege of Badon Hill. Curiously, Bede calls the home team ‘Bretons’. He uses the term ‘Brettones’ in his (Latin) text rather than his usual ‘Brittaniae’, probably after Pytheas’ archaic term ‘Pretani’ (from P-celtic Pritani

14

) in order to identify them more clearly as Britons (and presumably celtic-speaking) rather than just ‘inhabitants of Britain’. This variation in an otherwise consistent text implies that Bede believed that even at the time of the battle of Badon Hill, at the end of the Roman occupation, there were other tribes in Britain, including

in his view

the ‘Scythian’ Picts, who would not and could not claim ‘Pretannic nationhood’.

Gildas was, in Bede’s words, the ‘Britons’ own historian’. Bede automatically excluded himself from such potential

British

bias by his statement. Saxons only occupied southern Britain. Bede, who spent his whole life in Northumbria, knew this and acknowledged northern England as an Angle-dominated region. Although he probably knew more about books than about the

southern peoples, Bede describes the distribution of the Saxons in southern Britain accurately and in detail. So it is difficult to see why he should be so concerned about Gildas’ accusations that the Saxons were the fifth-century invaders, attributing the intrusion instead to Angles, unless he knew otherwise and was honestly convinced that Gildas was plain wrong in this instance (as Bede knew he was elsewhere).

Elsewhere in chapter 15, Bede does give a breakdown of the ultimate Germanic origins of their various English equivalents, the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes. The former he specifies were from ‘Old Saxony’. However, he gives no dates for migration, and it is clear from the title and beginning of the chapter that he prefers to link the invitation episode specifically to the Angles.

Being a well-read, polyglot Angle in a senior ecclesiastical position, Bede should have known the truth about the Angles – gory or otherwise. We have to assume that Bede was native to Northumbria, having been taken into the monastery at Wearmouth at the tender age of seven, according to his own words.

15

Bede was proficient in Early Anglian. His disciple Cuthbert wrote that Bede was ‘learned in our song’,

16

in a letter written in Latin, but quoting Bede’s moving death-bed song in the Anglian vernacular as part of the same text.

Gildas’ origins are shadowy, and we do not even know for sure where he lived, although somewhere in the south-west seems likely.

17

Gildas is generally regarded as more of a religious than a political zealot. However, as a Briton described in Welsh biographies as a saint,

18

it would be consistent for him to have had political as well as religious agenda associated with the celtic-speaking regions of his Britain. He is supremely

and inventively offensive in his use of adjectives for Saxons, describing them as ‘a multitude of whelps coming forth from the lair of a barbaric lioness’,

19

and worse elsewhere, so there is no doubting the partiality of his feeling.

It must have been, to excuse the pun, galling for the celtic-speaking nation to have seen the gradual cultural encroachment of ‘their south Britain’ over hundreds of years. So annoying, perhaps, that it might explain why Gildas was creative with Saxon history. Exaggerating Saxon people as recent interlopers in the south, and thus illegitimate, may have had something to do with his own agenda. The Saxon kingdoms of the south could have simply represented linguistically related elite takeovers which happened either during or before the Roman occupation. These takeovers could have been of long-standing settlements originally settled from the Continent (e.g. those referred to long before by Caesar and Tacitus). If so, Bede may have had good reason to correct the error.

I shall return shortly to the archaeological evidence for cultural continuity in the Saxon kingdoms of the south, but there is another set of clues to be found in the Old English landscape which tend to enlarge the gap between the linguistic-cultural histories of Angles and Saxons. These are runes and rune-stones.

Before discussing them, I should recap on the history of the main sources of stone inscriptions and other more portable, nonperishable pieces of text, including coins. Writing first appears

in Britain in the form of Roman characters on engraved coins in the century before the Roman invasion. Non-Romanized names of local rulers were used. Coin use was largely restricted to south-east England, and before local minting started, coins were imported, originally from Belgica. As far as the text language is concerned, practically all other inscriptions in England throughout the Roman period were in Latin. Significantly,

none

were in celtic or any other vernacular. The names in stone were mostly Latin as well, in contrast to the naming of coins.

Then there is a hiatus in the immediate post-Roman period. South-east England stopped inscribing stones, and by the time inscriptions started up again they were in Anglo-Saxon or Medieval Latin, with still practically no evidence of celtic use in any part of England except the West Country (

Figure 7.4

). In contrast to the near-complete absence of celtic inscriptions from any period in England, the non-English parts of the British Isles, in particular Ireland, Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria and Argyll, had many inscriptions in celtic. These used mainly Roman script, but also Irish Ogham characters, starting from the end of the Roman occupation and covering the Medieval period.

It is against this geographical background that a new script appeared on stones and ornaments in certain parts of England, replacing Roman script in the post-Roman period for up to two hundred years and then lasting for a further four hundred after Roman script reappeared. This script is

runic

, and consists of an alphabet with characters made up mostly of short lines set at angles, such as could be cut into wood with a knife. Unlike the celtic inscriptions of the Atlantic coast, inscriptions that used Roman script and Latin were slower to return to ‘Anglo-Saxon’

England. The Cambridge expert on runes Raymond Ian Page brackets the gaps in time and space: he ‘suspects the earliest example of Roman script used in an Anglo-Saxon environment to be the gold medalet issued by Bishop Leudhart, who accompanied the Frankish princess Bertha to England (c.580) on her betrothal to King Æthelberht of Kent’. Even this was Frankish and imported. ‘In the fifth and most of the sixth centuries the only recorded script for Anglo-Saxons seems to have been Runic.’

20

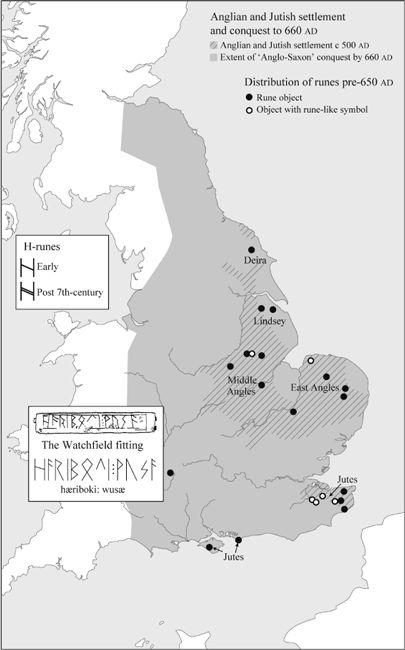

Runic inscriptions, in their sparse distribution (Figure 9.2), are thus the earliest and only direct written record of the new people from over the water, and they give clues to how those people spoke in the first two centuries after the ‘invasion’.

The runic script is often associated with magic, the occult and archaic ritual, and was exploited in a whimsical manner to great popular effect by Tolkien in his wonderful

The Lord of the Rings

. Runes also have a more prosaic meaning in the

Oxford English Dictionary

: ‘A letter or character of the earliest Teutonic alphabet, which was most extensively used by the Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons’.

Exactly when and where runes were invented is unknown, but the most likely location, based on frequency and age, is southern Scandinavia, probably Denmark, and certainly before

AD

400.

21

Munich-based linguist Theo Vennemann, has an interesting theory of the origins of runes. Based on a number of interlocking stylistic, phonetic, semantic and structural features, he argues they are derived from Phoenician script, not Roman or Greek. In his view this influence occurred in Denmark between the time of a Carthaginian colonization of the northern Atlantic coast, namely between Himilco’s voyage (c.525

BC

see pp. 35–40) and the end of the Second Punic war (201

BC)

when Carthage lost all her European possessions. This could also have been the time of Proto-Germanic.

22

The relationship between Scandinavian and English runic inscriptions is a fascinating historical puzzle, but before going any further I should point out that, in their distribution in England, they should be more strictly described as Anglo-Jutish, rather than Anglo-Saxon, since in Page’s words, Wessex and the west Midlands are virtually empty of runes. This exclusion also extends to Essex, Middlesex and Sussex, but not to the Jutish kingdoms of Kent and the Isle of Wight. I shall come back to the significance of the ‘Saxon voids’ shortly.

Figure 9.2a

Runes dated to before

AD

650. These follow the early Scandinavian runic orthography (II) and are found exclusively in the regions of initial Anglian and Jutish settlement, although most of England had been ‘conquered’ by

AD

660. This is consistent with Bede’s Anglian invasion – and only a limited elite one at that. (The only exception is the ‘Watchfield fitting’ (inset), in west Oxfordshire near Badbury Hill.)

Page places a dividing line of

AD

650 between the earlier and later runic monuments. His choice is based on what he sees as a number of relevant factors, including ‘There are no Old English Manuscripts [for linguistic comparison] before 650

AD

’ and ‘Surviving Old English manuscripts only cover part of the country, omitting large areas such as Lindsey, western Northumbria and East Anglia.’

23

Furthermore, datable runic-inscribed coins appear only after this point. The earliest runic monuments before 650 appear in all the locations normally associated with the early Anglo-Jutish intrusions, that is to say

limited

regions either side of the River Humber (Deira and Lindsey), the Wash (Middle Angles), Norfolk (East Angles), and Kent and the Isle of Wight (both Jutish) (

Figure 9.2a

).