The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (17 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 3.1

A clean sheet for the British Isles. During the last Ice Age most of the British Isles was covered by an ice cap. The rest of the extended landmass, including north-west France, was uninhabited polar desert. Northern Spain and southern France held the western refuge populations, identified respectively by Solutrean and Badegoulian cultures. Farther east in Europe, a much larger collection of refuge areas existed between the Balkans and the Ukraine. Italy was continuously occupied throughout the LGM, but at present there is no evidence for its role as a source population for recolonization elsewhere.

Parts of eastern France, by contrast to Germany and Britain, benefited from a slightly more benign landscape suitable for hunting, with dry grassland extending possibly as far north as the Champagne region. There are consequently a couple of LGM sites of human activity dated to around 18,000 years ago, in northeastern France. After 16,000 years ago, such activity also reappears in Belgium, southern and eastern Germany, and the Rhineland.

3

These few, scattered north-western LGM sites contain stone tool types matching the two Ice Age cultures,

4

found in the more populous regions farther south in France and Spain, where resident

refuge populations held on throughout the freeze. So the implication is that before 17,000 years ago these heroic north-western pioneers were mounting intermittent or seasonal recolonizations, taking advantage of rapid oscillations of world temperature, rather than relict northern groups hanging on over the LGM.

5

There is good archaeological and genetic evidence for at least four areas of southern Europe having served as refuges for Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers during the LGM.

6

I have already mentioned the extraordinary LGM human persistence in the Ukraine. This was largest and most active refuge, extending into Northern and Eastern Europe and south-west towards Moldavia. Geographically, and for cultural (i.e. archaeological) reasons, Slovakia and parts of the Balkans can probably be included this eastern group, while Italy in the Mediterranean and south Central Europe formed a central southern refuge and remained largely occupied throughout the LGM. While these refuge regions are fairly widely separated from one another, it does not mean that they were each necessarily homogeneous refugee camps. They were probably each made up of zones with some degree of difference in genetic mix. The refuge for southwest Europe was spread either side of the Pyrenees in southern and eastern France, the Basque Country, and other northern coastal parts of Spain such as Galicia and Catalonia (

Figure 3.1

). I shall therefore not always stick to one label for each refuge.

In my book

Out of Eden

, in which I traced the Palaeolithic peopling of the world, I made a big deal out of a general observation deriving from the geography of gene trees, that ‘once they got to their chosen new homes, the pioneers generally

stayed put, at least until the Last Glacial Maximum forced some of them to move’. The recolonization of Europe after the LGM was no exception to this rule, and these pioneer hunters then chose to return to just those places they had taken refuge from. Once settled, a founding population is hard to dislodge.

7

The pioneers achieved this just after 16,000 years ago, when Scandinavia and the Baltic were still covered in ice, by demonstrating, in both the archaeological and the genetic record,

8

possibly the highest rate of population expansion Europe would see until modern times. Archaeological records for this Late Palaeolithic period show evidence of twice as much human activity (measured in radiocarbon dates), lasting for longer (about 3,000 years) than either the Mesolithic or the Neolithic expansion, which began respectively around 6,000 and 8,000 years later (

Figure 3.2

).

The earliest archaeological evidence for the recolonization of north-west Europe comes from the Rhineland and southern Germany, to where Magdalenian cultures (see p. 125) had spread shortly before 16,000 years ago. Belgium, the Netherlands, eastern and northern Germany, and Poland then rapidly lit up with numerous new sites of occupation as the Magdalenians spread into the North European Plain.

9

The British north-west corner of Europe was not left out in this recolonization. Our stone tool styles have been named

Creswellian

after the cave sites at Creswell Crags (

Figure 3.8

). Archaeologists have recently begun to show just how early Britain was re-entered, starting only slightly later than in the Continental north-west, at 15,000 years ago. A number of sites in England, as far north as Nottinghamshire (the Creswell Crags in particular), show human activity at this time. The Creswellian culture appears to have extended through Norfolk across to the other side of the North Sea (which was dry at the time) into Belgium, the Netherlands and, in particular, Frisia (

Figure 3.8

).

10

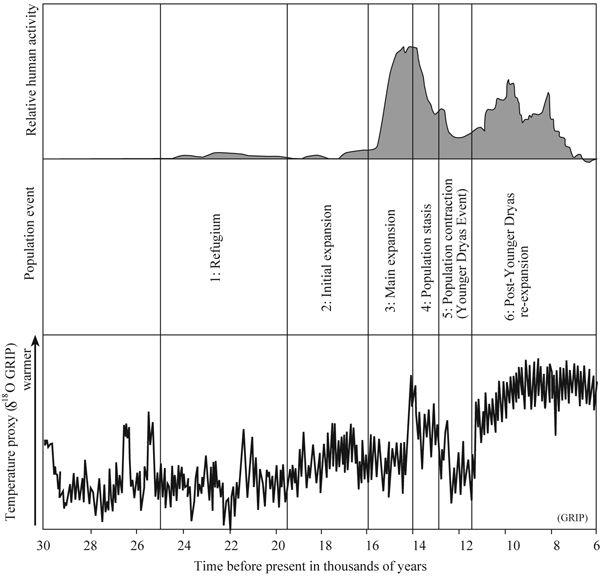

Figure 3.2

Human activity in northern Europe through the Ice Age and Younger Dryas. From zero population during the LGM (1, 2), the greatest expansion was immediately afterwards (3), falling (4) to a non-zero low during the YD (5) and rising again during the Mesolithic (6). (‘Relative human activity’ is a measure of human population in northern Europe, derived from the number of human-associated radiocarbon estimations (calibrated with Calpal). ‘d18O’ GRIP is a proxy measure of global temperature, ‘up’ being warmer.)

Other Late Upper Palaeolithic sites with a clear Creswellian signature are found in the West Country, in the caves of Devon

and Somerset. These include the famous Cheddar Gorge and other limestone caves well known to tourists. Just what was going on farther west on the Atlantic fringe at this time is not clear. Creswellian sites are found on the south-west tip of Wales, near Haverfordwest.

11

But it has always been assumed that there was no occupation of Ireland earlier than 10,000 years ago (based on archaeological evidence from the far north, in the lower Bann Valley near present-day Coleraine, and in the south-west, in the Shannon estuary).

However, between 15,000 and 10,000 years ago Ireland was connected to the mainland in the south and had a much larger surface area, in spite of the ice cap to the north. Any earlier coastal settlements of those times would now be deep under water. The Creswellian findings in Somerset and Devon suggest that there may well have been earlier Irish habitation, and this is supported by the genetic evidence from Ireland, which I shall come to shortly.

Perhaps one of the most illuminating records of our hunting ancestors comes from their rich and varied cave art (Plate 4). Church Hole, one of the Creswell Crag caves, possesses a richly carved and engraved ceiling. Bas-reliefs are a particular and unusual feature of Church Hole,

… which is of huge importance not only because of its quantity of figures, but also their variety (at least six kinds of animals, plus two or three species of bird, together with ‘vulvas’, etc). In addition, a few of the many peculiarities observed so far can be mentioned: e.g. the fact that, with the exception of the large stag and the first bison engraving detected nearby, and a possible bear bas-relief, which are complete, most figures comprise only parts of the animal, primarily the head or forequarters.

12

The first colonizers of any region have the opportunity, not available to latecomers, to imprint their own particular style and determine what follows. In the genetic record there is an exact analogy to this archaeological explosion of human activity. The first colonizing gene lines often establish the genetic landscape in a way that long outlives the event. In the British Isles this imprint is still clearly with us. The genetic terms ‘founder effect’ and ‘drift’ are perhaps more prosaic than those used to describe the rock art and stone tools, discovered by archaeologists at sites such as the Creswell Crags, but they still bear the signal of first-comers.

Leeds geneticist Martin Richards has conducted a massive study of all available evidence for migrations in Europe with thirty-seven international collaborators. They focused on mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down the maternal line and provides us with the most robust method we currently have for dating any part of our genome.

13

If we look at maternal prehistoric contributions to the modern gene pool over the whole of Europe in this study, 21% of extant lines derived from pre-glacial migrations and 51% from the Late Upper Palaeolithic just after the Ice Age (the latter from around 14,500 years ago in their study). For the rest, 11% each were contributed by the Mesolithic and Neolithic and around 4% by the Bronze Age.

14

In north-west Europe (excluding Scandinavia), the Neolithic component was higher at 22%, but the Late Upper Palaeolithic contribution to the modern gene pool was still over 50%.

15

In other words, over half our maternal ancestors arose from southern refuges and arrived in north-west Europe just as soon as the melting ice allowed.

16

Our pioneer-mothers were tough!

Martin Richards’ founder analysis of the European maternal gene pool took as its starting point the Near East as the ultimate

external

source of all genes coming in, but it is clear that the Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP) contribution results mainly from re-expansions from Ice Age refuges

within

Europe. So, when Richards and colleagues looked at the LUP expansion in the Basque Country, the best modern representative of the southwestern refuge, they found a massive 60% LUP contribution to locally extant European gene lines.

17

A similar conservative and indigenous European pattern has previously been argued for Y-chromosome data, but without the same detailed knowledge of gene line dates.

18

As we shall see, my own analysis of the Y data, separating and dating individual gene lines, supports this concept of a very large LUP colonization, although I am suggesting a rather larger Mesolithic component for the British Isles than in Richards’ analysis of north-west European maternal lines.

The pioneers who came after the ice did not just establish first-come-first-served priority in the north, but they expanded and flourished in numbers as great as at any time in prehistory. This teeming fecundity of hunter-gatherers runs counter to the idea that humans did not achieve the sophistication and technology needed for successful population growth until the Neolithic agricultural period.

19

But it is even more stunning when we consider that most of Europe was still very cold at the time – rather like parts of northern Siberia today.

The climate itself may explain this anomaly. As anyone who has been to a wildlife park, or watched wildlife documentaries, can observe and deduce, it is easier to detect and hunt prey if you can see it. Grassland, with or without scrub, is therefore of more value for most hunters than dense forest. Likewise,

most grazing beasts get more sustenance from grassland than in the forest, particularly if the forest is dense and coniferous. Immediately after the end of the LGM, a warmer period from 16,000 to 12,500 years ago transformed the dry European steppe tundra and polar desert into sweeping rich grasslands supporting a huge biomass of ruminants. But the forests had not yet returned, and, as on the Mammoth Steppe of Eastern Europe and Central Asia,

20

there were rich hunting fields if you were able to dress warmly and hunt big game.

To me, what is most interesting about the massive population expansion of the early West European pioneers is that much of the genetic landscape in the whole region was likely to have been ‘set in stone’ by the end of the Palaeolithic. Irrespective of the relative size of later Mesolithic and Neolithic contributions, this was long before the events that most British people now use to define their roots, such as invasions of Celts, Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. This implication of ‘old blood’ gives a more conservative complexion to the peopling of the region that is borne out repeatedly the more we look at the detail of genetic distributions on the landscape.