The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (33 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 5.8b

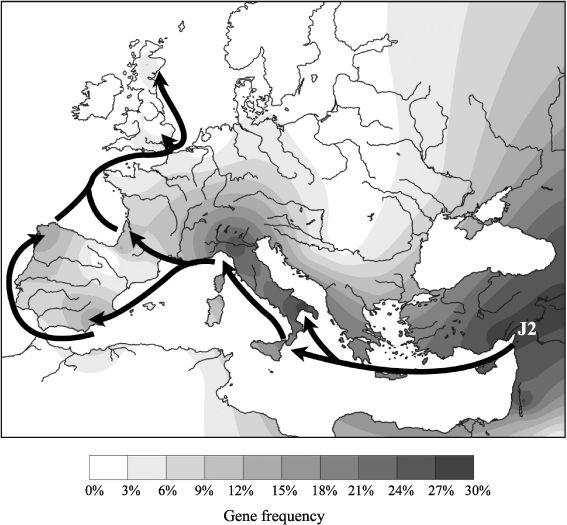

J2: Male Neolithic gene flow west along the Mediterranean. J2 is of Near Eastern origin and expanded from the Levant during the Neolithic. Part of this expansion travelled via Italy and then round Spain, eventually arriving in the British Isles, affecting Scotland and southern England but not Ireland. J2 is a putative geographic associate for the Vennemann hypothesis of additional maritime spread of Semitic languages to the Atlantic coast and British Isles during Neolithic.

The overall effect of J2 on Britain was largely similar to E3b and I1b2, in its size and wide southern British distribution, except that J2 is represented in Scotland with a highest frequency of 7.3% in the old Pictish town of Pitlochry and largely missed out on Wales (

Figure 5.8b

). Multiple J clusters show founding episodes dating to the Neolithic period in southern Britain.

Such a distribution, and the age of the founding British, E-M78-α and J2 clusters, suggests that there was a long trail of Neolithic gene flow into mainland Britain from the eastern Mediterranean via Italy and Spain, mainly bypassing France. However, the different sources of these lineages in the eastern Mediterranean, one in the Near East, the other in the Balkans may have implications for the languages each carried.

Which languages those Neolithic boats were carrying, as they travelled west along the Mediterranean via Italy and Spain, is a matter of speculation. The ancestor of celtic is a strong candidate from earlier discussions, but in that case, the male lines E3b and I1b2 moving west from the Balkans

88

would seem the more appropriate passengers than J2, who derives ultimately from the Near East.

89

This geo-linguistic speculation is partly because of the closer linguistic affiliations of celtic with Germanic and Romance languages than with languages of Greece, Turkey and the Levant and partly because of the distribution of J2. We will come back to an alternative role for J2 a little later.

If we recognize the contribution of the Balkan Ivan male gene group to Neolithic expansions within Europe, the Amazonian imbalance between migrating male and female Neolithic lines into north-west Europe and the British Isles is partially redressed. This still doesn’t quite explain why some Anatolian females apparently joined hands with Balkan males and took a trip up the Danube. The higher rate of drift in the Y chromosome with loss of Near Eastern lines en route, in a similar fashion to the Saami epic migration example, could be one reason.

But of course drift effects may occur in maternal lines as well. A fascinating study of ancient DNA by Wolfgang Haak of Gutenberg University (and colleagues) recently published in the journal

Science

does offer us a window into this gender paradox of the LBK-associated expansion, but it introduces even more questions than it answers.

90

The sort of reconstruction I discuss in this book mainly addresses DNA obtained from modern populations. The obvious reasons for this preference are that there are thousands of times more living DNA sources than viable ancient samples, and fresh DNA is much easier to analyse. But every now and then ancient DNA can provide the sort of information required to validate or falsify the picture obtained from modern mtDNA distributions.

The Haak study obtained mitochondrial DNA from skeletons excavated from sixteen Neolithic sites in Germany, Austria and Hungary. Eighteen of the twenty-four mtDNA sequences they managed to extract belonged to well-recognized European maternal types, but their relative frequencies indicated a bias towards lines that entered Europe during the Mesolithic (T2 and K) and Early Neolithic (U3, T1 and J). The others (seven of the eighteen) belonged to the older Helina or Vera groups.

91

Admittedly the sample size is small, but the result is consistent with a real spread from Anatolia up to the north-west, but straddling these two early periods. The Mesolithic-dated lines outnumber the Neolithic-dated lines by 7:2, reinforcing the idea that the LBK may have been more of a cultural spread than a pioneering migration. These people could have been following an existing network trail up the Danube from the Balkans which was already established during the Mesolithic. Even the first LBK settlements spread up the Danube very suddenly and did not initially exhibit a full Neolithic cultural package. On this basis,

one could suggest that the pre-existing populations, who might possibly be expected to have carried Mesolithic gene lines as well,

92

received culture and maybe some genes from their cousins farther down the Danube. If the Neolithic dating of the maternal lines is confirmed and they were actually joining pre-existing Mesolithic settlements, they might not be expected to dominate the picture.

Apart from raising such Mesolithic–Neolithic quibbles, the real surprise is that 25% of the lines Haak identified belong to an unexpected migrant newcomer, N1a. There is no clear N1a homeland, and she is rare where she is normally found, in scattered parts of West Eurasia, the Red Sea and South and Central Asia. Interestingly for us, N1a made it to Scotland, providing supporting evidence for a northern-route Neolithic input. The N1a gene types found in the Neolithic graves belong to two related sub-clusters, which are distributed evenly, one through Europe and one through west Central Asia, and are extremely uncommon even in these regions. The Central Asian type was found in a Hungarian Neolithic sample in the region of the Lower Danubian (AVK) Neolithic cultural region. N1a is virtually absent from Anatolia, the putative source of migrating Near Eastern farmers,

93

but has been found in a Scytho-Siberian burial in the Altai region.

94

The ultimate geographical source of N1a in these north Central European Neolithic burials is a matter of complete speculation. They might even have come from eastern Scythia (Kazakhstan), the reputed home of the female Amazon warriors, who Herodotus tells us intermarried with Scythians to found the famous warlike pastoral-nomadic tribe, the Sarmatians.

95

The latter were recently resurrected by Hollywood to serve under King Arthur in a Hollywood movie.

96

But before I give false cause for a tale supporting a Wagnerian view of the Amazonian origins of flaxen-haired Brünhilde and the Valkyries, and other Norse heroines, I should point out that N1a is conspicuous by her absence in modern German populations, thus posing another question: what happened to her? Haak and colleagues tested and rejected the possibility of loss by simple drift, offering the default hypothesis that ‘the surrounding hunter-gatherers adopted the new culture and then outnumbered the original farmers, diluting their N1a frequency to the low modern value’. The dilution–acculturation view is consistent with the non-N1a types found in the graves, most of which are themselves now much less common in the Austria– Germany region, the modern picture being dominated by Helina. This study provides

direct genetic

evidence supporting the view that the ultimate numerical impact of the Near Eastern Neolithic invasion on Europe was generally underwhelming. This view, which is argued in this book and many genetics papers of the past decade, is that the Near Eastern intrusion during the Neolithic accounted for not more than a third of modern European gene lines, and usually rather less.

97

Another unexpected result is that the dilution and loss of the maternal N1a could explain to some extent why the invading male Balkan Ivan line outnumbers maternal Neolithic Balkan immigrants to Northern Europe. If there were some immigrant women from the Balkan region among the first LBK settlements, they might have remained in those first settlements while all-male parties moved on to found new settlements with local wives.

At this stage, it looks as though the British Isles had a complex new input of female and male gene lines during the Neolithic period which amounted to between 10% and 30% of extant populations today. Several familiar patterns can be discerned as well as a couple of unexpected ones.

The first point, which has been stressed repeatedly throughout this book, is that the British Isles have always received two broadly separate inputs from the European mainland: one from across the North Sea and the other coming up from the south along the Atlantic coast. The Neolithic was no exception to this rule (Figures 5.6a and 5.6b), although the balance and ultimate origins of the gene flow were rather different from the preceding Mesolithic. The southern influence, ultimately from the Balkans and the Near East, came along the Mediterranean coastal route via Spain and southern France. This can be seen to have contributed nearly half the Neolithic male lines in southern England and the Midlands and about a third of those in eastern and northern England, but very few in Scotland (

Figures 5.6

–5.8).

Consistent with this, the northern Neolithic influence, as represented by Ian on the male side, appears to have come up the Danube with the LBK culture, spreading into and throughout England as far as the Welsh borders and to Scotland. The difference here is that whereas England’s incoming Neolithic gene flow looks very similar to that received by nearby Frisia, Scotland and its islands may have received their main Neolithic input from Norway, on both the male and the female side (

Figure 5.7

).

These impressions persist even after making allowance for the later Viking invasions.

The second impression is that the overall impact of Neolithic lines on the British Isles is patchy. Male post-Mesolithic intrusions from any source – most of them Neolithic – range from a low of 7.5% in Irishmen with Gaelic names

98

to a high of 39% in Abergele, north Wales (

Figure 5.4

).

99

Irish females have a low frequency of Neolithic lines (13%)

100

compared with the overall frequency of 22% estimated for north-west Europe.

101

The conservative Irish picture fits with the genetic evidence for substantial indigenous re-expansion during the Neolithic (

Figure 5.5

).

The map (

Figure 5.4

) of combined putative invading male Neolithic lines shows the highest local British rate of ‘intrusion’ in Abergele, north Wales at 39%, most of which is contributed by E3b (at 33%). Regionally, England had the highest rates (range 10–28%), followed by Wales (range 10–33%) Scotland (range 6–19%), Cornwall (10%), and Ireland (range 6–9% overall). These rates are in general lower than in the northern Neolithic source region in north-west Europe, where percentages for the equivalent intrusive Neolithic lines range from a low of 25% in Frisia to a high of 35% in northern Germany. Scandinavia has between 27% and 35% Neolithic male lines. In the southern Neolithic source region of Iberia, the highest rates of Neolithic male gene lines are in the coastal regions of Galicia (38%) and Valencia (36%), with the lowest rate in the Basque Country at 10%.

102

The differences between England, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall and Ireland in terms of Neolithic and previous intrusions are sufficiently marked to indicate that a progressive pattern of regional

genetic identity was already well under way by the Neolithic. We should remember, however, that the demographic division of Britain started as far back as the Mesolithic or earlier. On the east of the Welsh border, Ingert was present from just before the Younger Dryas, and R1b-7, 8, 11 and 12 from immediately after. Along the Atlantic fringe to the west, the presence of the ‘Irish’ Rory (R1b-14) cluster in Ireland and up the western side of Scotland, had already begun to separate Ireland, Cornwall, Wales and the Scottish Atlantic coast from the rest of the British Isles. These regional identities persist in genetic distance maps whichever groups of markers are used, specific or non-specific, Palaeolithic, Mesolithic or Neolithic.

103

Do the divisive genetics of the British Neolithic help with the ‘Celtic question’? Not very neatly. The low rate of intrusive Neolithic lines for Ireland (6–9%), which is found even among Irishmen with impeccably Gaelic surnames, is consistent with previous results for maternal lines, and demands an explanation. The simplest and most obvious explanation is one I have suggested already: if pre-existing Irish Mesolithic populations, observing new fashions from afar, undertook their own Neolithic Revolution, importing more culture than people, they might only have absorbed minimal ‘Neolithic’ gene lines from the Mediterranean to the south, rather than suffering a major elite invasion.