The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (28 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

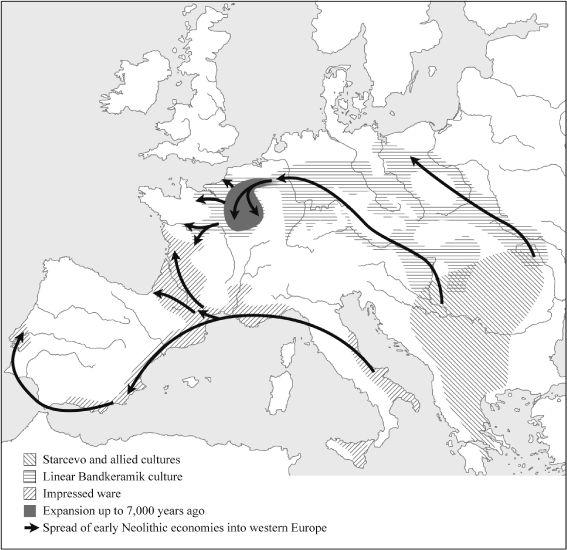

One particular style of pottery is most frequently associated with the spread of the Neolithic in Central and Western Europe. It has a distinctive decoration, with straight or linear bands, and is usually known by its German name,

Linearbandkeramik

(LBK), which simply means ‘ceramics (pots) with linear bands’. Much has been made of the rapid spread of the LBK style, apparently up the Danube from its homeland in Hungary about 7,500 years ago. Reassessment of the sequence has only highlighted the

rapidity: LBK reached Austria, and then Frankfurt in Germany, almost before it left Hungary, covering 800 km within 100 years.

8

However, the land use of these early western LBK-associated settlements was still what might be described as transitional Mesolithic, with foraging and only small-scale animal husbandry and horticulture.

9

An aversion to full-on agriculture might suggest that they were unable to clear forest, but this does not seem to be the case, so perhaps it was the pots, domestic animals and ideas which were moving and being adopted within a pre-existing network of Mesolithic tribes in Central Europe, rather than new people migrating and replacing them or clearing spare forest.

After reaching the Central and North European plains up the Dnestr and Danube Rivers, LBK then spread rapidly north down the Vistula, Oder and Elbe. It did not, however, move right up to the Baltic or Atlantic coasts (so avoiding the settled coastal Mesolithic communities), but instead swung west and southwest through the Netherlands and Belgium, arriving in northern France by 7,000 years ago and finally reaching Normandy and its coast 500 years later.

10

An eastward movement of LBK went round the Carpathians to Poland and on to the Ukraine at the same time as the westward spread, but pots had already appeared among Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Poland and western Russia and the lower Volga long before, around 9,000 years ago.

11

At the same time as the Early Mesolithic (i.e. pre-agricultural) spreads of pottery were taking place in north-east Europe, another type of ceramic flow sailed west along the north coast

of the Mediterranean from the Italian and Sicilian coastlines to the Mediterranean coasts of France and Spain nearly 9,000 years ago.

12

The ceramics in this instance had attractive dotted and dashed lines created by making impressions on the wet clay with the edge of a cockle (

Cardium

) shell. Appropriately, this pottery is called Cardial Impressed Ware or just Cardial Ware.

Significantly, none of the early Cardial Ware sites show evidence of a full farming lifestyle (e.g. cereals and animal domestication) apart, possibly, from some sheep.

13

Cereals did not make their appearance at these sites until after 7,500 years ago. From then, and over the next thousand years, Cardial Ware settlements appeared on the Atlantic coasts of France and the Iberian Peninsula. Their distribution (

Figure 5.1

) indicates that they probably took both of the same two routes that would be used by Phoenician and Greek tin traders much later on, namely through the Straits of Gibraltar and inland via Carcassonne across the Aude–Garonne corridor (see

Figure 5.1

and

Chapter 1

).

14

La Hoguette

is yet another style of early pottery, found mainly in France from 7,500 years ago which, with its associated material culture, seems to bridge the transition from the Late Mesolithic to the full Neolithic with ceramics, small-scale pastoralism and horticulture with cereal agriculture. The La Hoguette also fills in the geographical gap between the growing pincer movements of Cardial Ware in the south of France and LBK in the north. La Hoguette style was first found in Limburg, in the Netherlands, but is defined by bone-tempered pottery found at a site near La Hoguette in central Normandy. Although mainly found in the upper Rhone Valley, northern France, Switzerland and south-west Germany, in style La Hoguette resembles Cardial Ware farther south. Consistent with this south–north direction, a species of poppy,

Papaver segiterum

, originally from the south of France, was carried north as well. La Hoguette probably antedates LBK around the middle Rhine region where the styles overlap and even hybridize.

15

Figure 5.1

The early spread of the Neolithic into Europe, as told by pots. Two types of pottery spread through Europe with the Early Neolithic from the Near East: Linearbandkeramik (LBK) spread up the Danube from the Balkans to the north-west, while Cardial Impressed Ware spread along the Mediterranean coast and up through France.

In La Hoguette, and its association with elements of hunter-gathering, forest clearance, horticulture and limited animal husbandry of sheep and goats, we see yet another example of

Mesolithic networking and opportunistic cultural acquisition (an example of

acculturation

in action). The direction of movement of La Hoguette from south-west to north-east towards the Rhine, suggests that the importance of the LBK to the West European Neolithic to the south-west of the Rhine may have been overstated and is only part of the story. What is more, the two directions of influence on the British Isles, one from the south-west and the other from central Northern Europe, seem at this point to be forming a recurrent pincer pattern, setting the scene for the next 7,000 years.

So, it appears that the earliest movement of pottery among Mesolithic groups, both in the north and the south of Europe, was a harbinger rather than a trademark of the spread of farming and farmers. It may be that the view of a mixed hunting, foraging, pastoral and horticultural lifestyle of the Late Mesolithic as only transitional is a biased perception. This pattern of ‘mixed rural economy’ is still the norm for so-called farming cultures in the interior jungles of South-east Asia and New Guinea today, where a tiny minority are nomadic specialist hunter-foragers, but the majority of sedentary farming folk also hunt and gather. I shall return shortly to the implications of mixed lifestyles for the question of population replacement vs acculturation in the Neolithic.

The year-by-year spread of two branches of the Neolithic cultural package from the Near East via different routes towards the Atlantic coast and finally the British Isles has been studied in minute detail by archaeologists. We have a dated progress report of how farming and pots gradually impinged on, if not necessarily replaced, Mesolithic hunter-gatherer lifestyles. Yet there are still several big questions which are very relevant to the peopling of the British Isles. One is how many people were

involved in the revolution: in other words, did the newcomers replace the old established populations? Another is what languages did they speak? A third is whether the British Isles had two separate Neolithic revolutions. A fourth – and this has only recently been asked – is whether the Neolithic agricultural lifestyle was necessarily more nutritious, healthy and successful in generating population expansion in rich environments in Europe, than was huntin’, fishin’, shootin’ and gatherin’.

Rather than starting with the traditional questions, I shall go for the last first and work backwards. In my previous book on earlier humans (

Out of Eden

),

16

I pointed out that until recently most modern human populations have been considerably shorter than their hunter-gatherer forebears since the start of the Neolithic. We have to remember that today’s hunter-gatherers are obliged to eke out an existence in semi-deserts or deep in closed, inhospitable rainforests and are not representative of previous hunter-gatherers. Before the arrival of farming, they had a choice of richer environments. The main reason for this Palaeolithic/Neolithic height difference and for the variation between the heights of modern regional populations is nutritional rather than genetic. Today, some of the shortest peoples are those who consume a high proportion of grain products, or other bulk carbohydrate, as their main source of calories. Some of the tallest are those who have a high proportion of animal protein in their diets. Economically rich populations all over the world have increased protein as a proportion of their calories over the past century and have shown quite dramatic increases in average adult stature.

For the sake of brevity, I have rather oversimplified the picture, because the physiological reasons for these effects are actually quite complicated. What seems to be particularly important for adult stature is diet during the weaning period and whether weaning starts early with the use of grain-based porridges. Early infant weaning also has a profound effect on the breast-feeding mother in that it stops lactation, restarts her monthly periods earlier, allows her to become pregnant sooner, and thus ultimately leads to larger families.

The point of this preamble is that there is no good evidence that the agriculturalist’s diet was actually more nutritious than that of the hunter-gatherer in a rich environment, although it may have resulted in larger families.

17

Arguments for the success of agriculture based simply on improving individuals’ quality of nutrition are therefore likely to be specious.

There are of course other advantages that farmers had over hunter-gatherers. One is visible, fixed ownership of land, which in itself tends to move on the hunter-gatherers without recourse to violent conflict. This was probably a very important factor behind the apparent Neolithic takeover of Central Europe. However, we should remember that the Mesolithic fishers and foragers of the Atlantic coast had already settled and made their identity and territorial ownership very visible.

Another often-stated advantage is that a given plot of land is likely to have a higher per-hectare yield, more particularly in the form of vegetable calories and protein. This is true today, but may have had less relevance for labour-intensive Neolithic farming with the lower population densities of the past. It is also a somewhat artificial division, since both hunter-gatherers and farmers have mixed diets and lifestyles that depend on the

characteristics and productivity of the landscape they live in. In the jungles of Borneo, where I have spent some time trekking and working, farmers bring a considerable proportion of their diet to the table straight from the bush. Rice is consumed in these jungle longhouses more for status than as a staple.

Clearly there was – and is – an economic advantage to farming, otherwise we wouldn’t depend on farmers for food now, but early European Neolithic communities were not sufficiently densely populated to reap this bonus. However, in Mesolithic Europe there may have been a special territorial edge for anyone using the new culture, immigrants and indigenous peoples alike. This was the clearing and opening-up of the huge, dense forests that covered Europe during the Mesolithic (

Figure 5.2

). As we saw, during the Mesolithic the hunters progressively lost their huge cold prairies rich in large visible game and had to move to the hills, where the forest cover was thinner, or to the coast, where they could rely on supplementing their diet with seafood.

Closed canopy forest is not the paradise implied by the Robin Hood legends. Game is less plentiful and less visible; favoured fruit-bearing shrubs and trees are less accessible. Some academics studying the prehistory of peoples of Southeast Asia even suggest that an independent nomadic life in the tropical rainforest without interaction with the outside world is an impossible myth.

18

This is an exaggeration of reality, but present-day forest peoples, such as the Penan and Semang in Malaysia, do need to be super-specialized hunter-gatherers to be able to survive independently in their environment. Given the hardships of the closed forest, it is not surprising that population densities of hunter-gatherers there are low.

There still are a few truly non-agricultural forest-dwellers left in the South-east Asian, African and Amazonian tropical jungles, but their independent existence is vanishing rapidly as their formerly protective forests are logged and torched. What replaces tropical forests after felling or torching is extremely degraded in terms of biological productivity, because of the poor soil, but any post-Neolithic agriculturalist can scratch a subsistence crop on it, raise cattle or grow cash crops. Although the overall environment is impoverished, forest clearance does allow potentially higher population densities. The herding of displaced forest nomads into resettlement camps before they are ‘assimilated’ into the mainstream population may be accomplished with minimal violence – but often is not.