The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (29 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

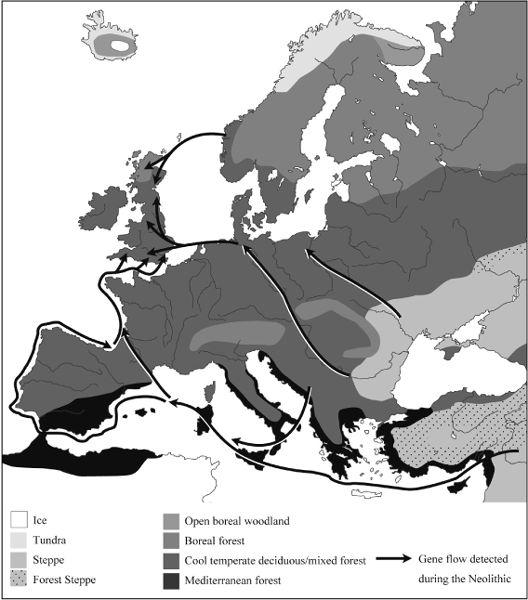

Figure 5.2

Invading the European forests and coasts. A summary of gene flow into western Europe and the British Isles as described in this chapter, also showing natural vegetation during the Neolithic. Two routes from the south-east had already been established during the Mesolithic. One went north-east of the Alps along central European rivers such as the Danube, while the other followed the coast of the Mediterranean, ending up on the Atlantic coast.

In contrast to the true forest nomads, who number very few, there are other traditional forest-dwellers throughout the world who maintain relatively higher local population densities by mixing hunter-gathering with a rotation of crops and food-trees on ever-changing small forest clearings called swiddens. What is more, marauding pigs and deer provide better targets for keen hunters in these opened-up areas. In the tropics, governments and their under-the-counter partners, the logging companies, are often keen to vilify and pass the blame to these modern mixed-economy groups as forest-destroying ‘slash and burn’ agriculturalists. As both sides know well, this is a lie. The boot is on the other foot. In fact, the swidden farmers have managed and preserved the forest for thousands of years.

The soil situation in Europe is different, because of the rich, thick loess deposited in large areas by the wind during the ice ages, so farming is and was more rewarding, given sufficient rain; but the practical message is the same as today: opening up closed forest can dramatically increase population density.

How could all these these comparisons between Mesolithic and Neolithic lifestyles help to explain the delayed Neolithic changeover in the British Isles? First, taking an overview, it

could partly help us to understand why the whole north-western Atlantic coastal region received less immigration during the Neolithic than did the rest of Europe (

Figure 5.4

). It could be because the long, tortuous Atlantic coastline was already occupied by well-fed, settled Mesolithic communities who had diverse food sources, identified with their own particular part of the landscape, and already had traditional trade links with southwest France and Iberia and the western Mediterranean.

For most of the heavily forested Central, Northern and Eastern Europe, on the other hand, the main water bodies were rivers, which acted as conduits for immigrant farmers from the south-east penetrating back to the Balkan and Anatolian agricultural homeland. These were rivers such as the Danube, Dnepr and Dnestr, which discharge to the south-east into the Black Sea and would have provided a route for the Anatolian and Balkan farmers up to the north and west. The source of the Dnestr points towards Poland through the western Ukraine. Travelling upstream, the great Danube, Europe’s aorta, creates a corridor penetrating between Romania and Bulgaria through Hungary, then on via Austria to southern Germany (

Figure 5.2

). Once across the Central European watershed, migrants would have found other rivers, such as the Vistula, Oder and Elbe, beckoning politely northwards and downstream towards the Baltic, and the Rhine and Seine inviting them towards northern France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

As Barry Cunliffe says:

Neolithic communities were well established in the middle Danube Valley and the Hungarian Plain by the middle of the sixth millennium [7,500 years ago] … The speed with which

these pioneer horticultural groups were able to spread through the forested loess lands of middle Europe was remarkable. It may, in no small part, have been aided by the sparseness of the foraging population. The forests of the loess were dense, and over very large areas supported in sufficient biodiversity to attract hunter-gatherers. For horticulturists ready to ring-bark ancient trees and to burn undergrowth, allowing the ash to fertilize the soil, the old forest was a congenial zone to colonize. By 5000

BC

huge tracts of Europe from the Vistula to the Seine had been settled …

19

As this passage implies, the idea that the Neolithic takeover of Europe resulted from forest clearance rather than the superiority of farming as a way of life is not new, but the problem has been in assessing population densities archaeologically and in determining how many people were real newcomers.

If we are to get any genetic handle on new migrations into the British Isles during the Neolithic, as opposed to acculturation and expansions of pre-existing Mesolithic populations, it is important to understand the evidence for so-called Near-Eastern Neolithic gene markers. What we need to establish is which of the two routes each gene line may have taken from south-east Europe – up the Danube to Germany, or south of the Alps along the Mediterranean coast to Iberia. While there is clear evidence for both routes having been taken by maternal lines that ended up in Britain, the southern route via Iberia and southern France seems to have flowed round the Basque Country, leaving it as a Mesolithic island with only 7% intrusion from the Neolithic.

20

Three maternal gene groups of Near Eastern origin have been fairly clearly identified as contributing ‘Neolithic’ entrants into Europe: J, T1 and U3, in that order of importance.

21

These were not the only contributors to Neolithic immigration, but together with others, they amount to around 20% of the extant European mtDNA pool.

22

While this proportion is much less than some enthusiasts had previously postulated, it still represents a significant event in European prehistory.

However, the entry of these maternal immigrant lines into Europe has been dated to around 9,000 years ago,

23

which, although appropriate for the Neolithic in Asia Minor and southern Turkey, would still fall during the European Mesolithic even for the Balkans in the south-east. The uncertainties in the dates are so large that these lines could have entered Europe either when most of the region was still enjoying its Mesolithic or after the start of the Balkan Neolithic, or even both. This should be borne in mind when considering how much of the expansion into Europe was a result of the new technologies and how much was anticipated by northward population spread in the Mesolithic, simply resulting from the dramatic climatic improvement after the Younger Dryas freeze ended.

24

The J branch contributes the largest proportion of Near Eastern Neolithic maternal lines overall to Europe. While most of the J component is not sufficiently well defined to allow us to trace exact routes within Europe, there are three J sub-branches which clearly had separate trails and can be used for this purpose. When Martin Richards and colleagues broke down the ‘Neolithic immigration’ into regional contributions, north-west Europe (including northern France, the Netherlands, Frisia and Lower Saxony) had the highest proportion of maternal immigrant lines,

totalling about 22%. Closer examination shows that a much lower proportion of such lines actually arrived in the British Isles (

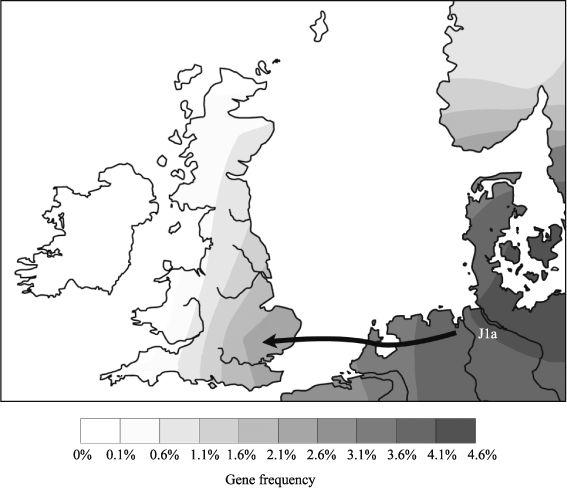

Figures 5.3a

and

5.3b

).

One particular J gene group, J1a, is strongly associated with north-west Europe, and has been labelled the LBK line, and even the Germanic line,

25

since it also follows the distribution of the Germanic group of languages in that area, including rates of up to 2.5% in eastern Britain. Dated in Europe to 5,000 and 7,000 years ago in two separate reports,

26

it would certainly fit a Neolithic expansion, although the uncertainties in these dates do not rule out the Late Mesolithic. J1a is also present in traditionally English-speaking areas of England, although at rather lower rates (2% vs 4%) than in northern Germany (

Figure 5.3a

).

27

The question, then, is when did J1a arrive in England – with the Anglo-Saxons, or earlier? There is supporting evidence, as we shall see later, for at least some intrusions into England during the Dark Ages from the putative Anglo-Saxon homelands. But the latter may have been a limited, males-only, elite invasion which left at home another maternal gene line, the female ‘Saxon’ marker that we would expect to have been on the longboats had colonization been the aim.

28

Figure 5.3a

Maternal representatives of the ‘LBK line’ reach England: this map gives maternal evidence of the final movement of the north-western European Neolithic into England in the form of the J1a gene line (originally from the Near East). (Arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography, although a reverse direction is possible here.)

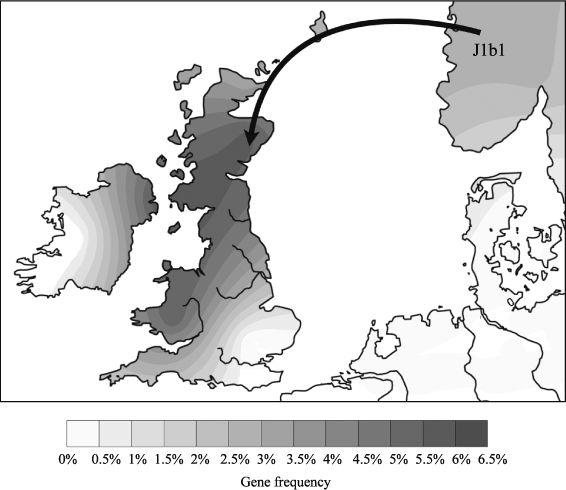

Figure 5.3b

Scandinavian mothers in northern and western Britain during the Neolithic? Maternal genetic evidence for migration carrying the Near Eastern line J1b1 into northern Britain during the Neolithic probably from Norway. (Arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography.)

The geneticist Peter Forster, an Anglo-German, suggests an alternative view to the idea of J1a arriving with the Anglo-Saxons in the Dark Ages: since, logically, J1a could not have come from north-west Germany without her sister, the Saxon marker, she may have derived from more westerly Germanic-speaking Dark Age invaders such as the Dutch, Frisians or Caesar’s Belgae. My simpler default explanation, which makes fewer assumptions, is that J1a arrived much earlier in England as part of the final movement of the north-western Neolithic, and so would not have included the Saxon marker anyway. Supporting such an early move is the fact that J1a itself subsequently developed a sub-clade in Northern Europe dating to about 5,000 years ago which, like the female ‘Saxon-H’, does not feature in Britain.

29

In competition with the northern J1a gene group, there is geographical evidence that a second main J branch, J2, known as the ‘Mediterranean-celtic branch’, took the southern route along the coast of the Mediterranean from the Near East via Italy, Sardinia, Spain and Portugal, bypassing the Basque Country to the French Atlantic coast. In its distribution thus far, J2 mirrors the spread of Cardial Ware moving west along the Mediterranean. After Brittany, however, J2 jumps across the Channel to the British Isles, where it is now found in particular association with Goidelic-celtic-speaking areas. J2 dates very approximately to 7,000 years in Europe,

30

which within the margin of error, would fit the spread of Cardial Ware. In other words, J2 could be a population marker for the Early Neolithic spread of Cardial Ware pottery along the Mediterranean coast. Whether this is in fact the case, and whether J2 is further associated with the spread of celtic

languages, are matters of tantalizing speculation, although at an overall frequency of less than 1.5% in the British Isles, J2 could hardly be called a major founder.