The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (24 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

The eight closely related Ruisko clusters, derived from Ruy, also seem to follow the same pattern of filling in the parts of the modern coastline of southern Britain that had been obscured by the continental shelf when the sea level was lower. We find that they divide roughly east–west on the landscape of the British Isles: two in the west, especially in Wales (R1b-11 and 12 –

Figure 5.5b

, and R1b-13 –

Figure 4.6

); two more on the south and east British coasts (R1b-7 and 8 –

Figure 5.5c

); and three small ones diffusely in the middle (R1b–2a, R1b–2b and R1b–3). These three sets of Ruy descendent clusters account respectively for 10%, 15% and 2% of extant British male lines. Collectively, these derived clusters account for 27%, which, when added to Ruy, make a total 45% Iberian ancestral contribution to modern British lines from these Mesolithic arrivals. However, clusters R1b-7, 8, 11 and 12 did not actually generate their re-expansions until the Neolithic several thousand years later, so 21% of the 45% ancestral contribution was effectively deferred to that period.

19

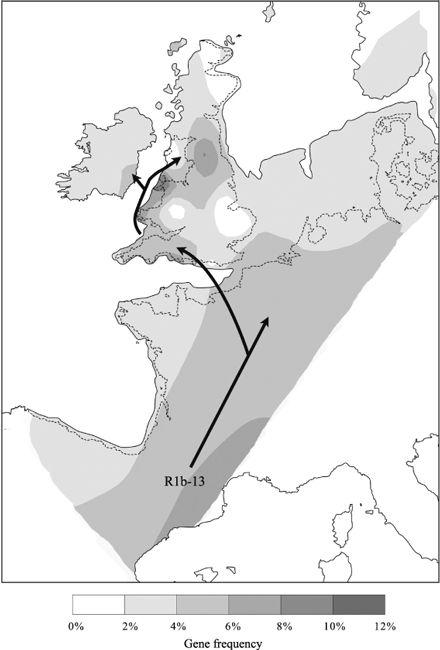

Three closely related clusters, R1b-11, 12 and 13, started to break up from a common Mesolithic British ancestor around 9,500 years ago. The first to split was R1b-13, which now dates to 7,800 years ago (

Figure 4.6

). It accounts for about 4% of British males today,

20

and has a similar distribution to Ruy, mainly along the western Atlantic fringe of Britain, with highest frequencies in north Wales (Llangefni) and Cumbria (Penrith).

21

Figure 4.6

Welsh colonists of the Mesolithic. This map demonstrates the impact of another common cluster derived from Ruy, R1b-13, which expanded northwards from the south-west European refuge during the Mesolithic. The gene flow follows the ancient extended coastline, which had now opened up to show the southern part of the English Channel. In this instance south-coastal England, Cornwall, Cumbria and Wales were targeted (arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography.)

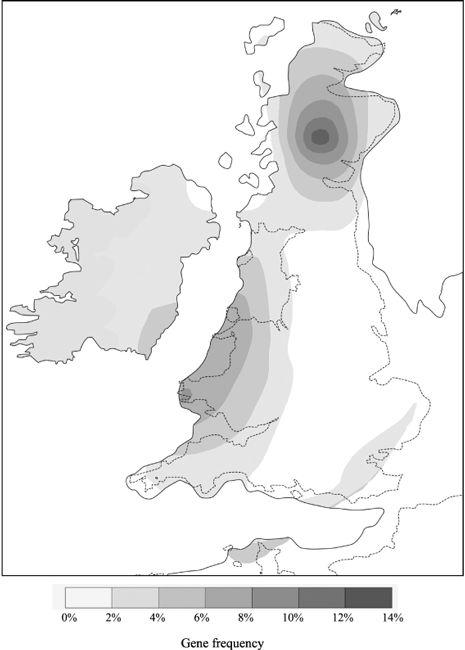

This British triple cluster R1b-11-to-13 re-expanded much later, during the Neolithic, into R1b-11 and R1b-12 (

Figure 5.5b

and

Figure A4

, Appendix C). The largest of these clusters was R1b-11, which characterizes the west or Atlantic side of Britain, from the Channel Islands through Cornwall, Ireland and Wales right up to Scotland and the Shetlands, and is uncommon on the east coast of England. R1b-11 accounts overall for about 6% of modern British males.

22

But, compared with R1b-13, there is a more northerly centre of gravity, in north Wales and Scotland (see

Chapter 5

, in particular

Figure 5.5b

).

So, although the ancestor of the two clusters R1b-11 and R1b-12 appears to have arrived during the Mesolithic, and they jointly account overall for 7% of extant British lines,

23

most of their diversity developed later with Late Neolithic population expansions. Since both these clusters expanded during the Late Neolithic period, they effectively made up for the relative lack of contemporary incoming Neolithic lines on the Atlantic coast compared with elsewhere in Europe.

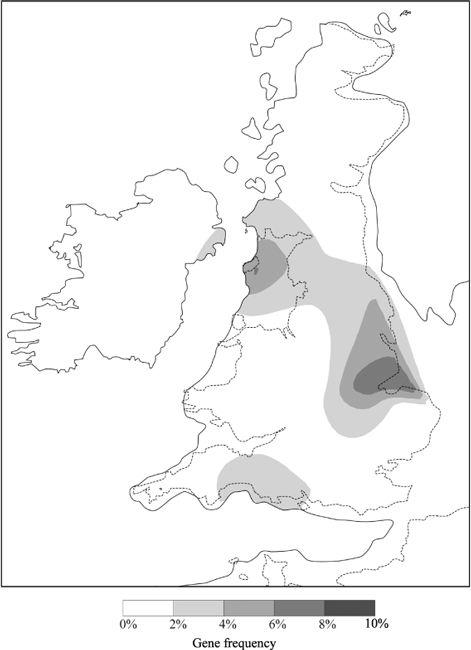

Another larger cluster descended from Ruy is an interesting puzzle for the European Mesolithic. This is R1b-8, which now constitutes 13%

24

of British male lines and is the second largest in our whole dataset, after Ruy. With apologies to the clan MacGregor for imperfect location, I am giving R1b-8 the nickname

Rob

, after Red Rob (‘Rob Roy’) because of his highest frequency in the north of Scotland (Durness 29%). Rob is defined by the root

Frisian Modal Haplotype

(FMH), which constitutes 7.6% of the full dataset and 8.6% of the British Isles.

25

The FMH is well represented in Denmark and Frisia, hence the name. But it is also generally common throughout the British Isles, where it is found along the south coast, including Cornwall, Midhurst and Dorchester, and in northern Scotland (

Figure 5.5c

). In each of the main British regions, at least one different Rob gene type is present in addition to the FMH: for example, the south-coast gene type is unique to Britain, with the exception of one instance in Frisia. The greatest diversity of Rob is thus found in the British Isles, suggesting that he arrived in Britain before Frisia.

Some geneticists argue for a recent Frisian invasion of England during the Dark Ages (see

Chapter 11

), based on the ‘evidence’ of Frisian/English genetic and linguistic similarity. In so doing they fail to recognize this alternative perspective of similar, parallel ‘ancient history’. The geographical distribution, diversity and splitting of these closely related twigs of Rob either side of the North Sea are much more likely to reflect trail choices made by Mesolithic colonizers than any recent invasions by Anglo-Saxons or Frisians.

Although Rob is aged around 10,000 years in Western Europe as a whole (

Figure A4

, Appendix C) and joined the

other Mesolithic clusters with Ruy from Iberia, he later broke up into much younger clusters in Northern Europe and Britain. The main expansions of Rob and his descendant cluster R1b-7 within the British Isles are local and later than the Mesolithic (

Figure 5.5c

) but none of them can be connected to the recent ‘Anglo-Saxon’ invasions.

26

I shall come back to Rob and his descendants, later during the Neolithic discussion in

Chapter 5

.

Overall, then, the Y-chromosomal evidence suggests that new Mesolithic immigrants from Iberia went mainly to the western and southern British Isles, contributing initially about 24% of modern lines, which is rather similar to the maternal figure. However, other Rob lines later evolved into more new clusters, so the Mesolithic immigration of these lines

ultimately

contributed an overall 45% of today’s British male lines, which would be larger than the previous Late Upper Palaeolithic contribution.

Additionally other clusters, already in the Western British Isles from before the Younger Dryas, split and expanded in the Mesolithic period (

Figure 4.7

). They included Rory (R1b-14a & b), R1b-4 and R1b-15a. These internal British re-expansions contributed a further 5.4% of Mesolithic lines surviving until today.

27

Another line on the western side of Britain dates locally from the Mesolithic period. This is I1b2, which is found at rates of 3% and less in the Channel Islands, south-west England, Wales and Ireland. I1b2 most likely came in during the Late Mesolithic from the western Mediterranean, where it is characteristically found, via the Iberian region, having originated in the Balkans (see discussion of the Ivan (I) group later in this chapter).

28

The other part of I1b, denoted by I1b*, is very uncommon in Western Europe but has a similar age and distribution to I1b2 in the western British Isles.

Figure 4.7

Mesolithic indigenous re-expansions in the west. During the Mesolithic much population expansion occurred among pre-existing populations in the west from before the Younger Dryas. In Wales and Scotland this included R1b-14b&c, R1b-4 and R1b-15a.

So, what else was happening in eastern Britain at the onset of the Mesolithic if we are seeing rather less Ruy offspring appearing on that side during the Mesolithic? The answer is not much. There was one descendant of Rox surviving there from before the Younger Dryas but re-expanding immediately after the YD.

29

This was R1b-6, the core type of which is unique to Britain. It is found in only 1% of the British sample population. The R1b-6 core type is a one-step minority derivative of Rox (i.e. one mutation different). Two-thirds of R1b-6 representatives are found in eastern England, the Channel Islands and Dorchester, while 82% are restricted to eastern England: Norfolk, Southwell, Bourne and York (

Figure 4.8

). The distribution of the founder type suggests R1b-6 may have mutated from Rox somewhere in the English Channel area (when it was mostly dry), and from there moved up into Norfolk and north-east England.

The decision of whether to go north-east, right up the Rhine/Thames/Seine/Channel Basin, and explore the ‘European’ side of Britain or just continue west along the Atlantic façade marks the first step in a pattern of recurrent geographically determined relationships that still divides England genetically and culturally from the rest of the British Isles.

Norfolk and East Anglia were still linked to the Continent at this stage. We saw in

Chapter 3

how Ingert (group I1c) may have moved up from the Balkans into north-west Europe and eastern England just before the YD (

Figure 3.8

). I1c-3 dates to just after the YD and features on both sides of the North Sea, in Norfolk and the Fen country and in Frisia. Several other Ivan lines found in eastern England date to the Mesolithic. These also link to the nearby Continent.

30

This first evidence of gene flow into Britain from the Low Countries the other side of the North Sea (Saxony, Frisia, the Netherlands and Belgium) leads me next to examine the relevance of what was going on in the northern part of north-west Europe during the Mesolithic.

Figure 4.8

Mesolithic indigenous re-expansions in the east. During the Mesolithic population expansion occurred among pre-existing populations in the east from before the Younger Dryas. This was rather less than in the west and involved just one sub-cluster, R1b-6, also found on the Isle of Man.

Moving away from the British Isles briefly, I should first like to paint in a bit of the picture of possible genetic events in northern Scandinavia during the Mesolithic. This is not out of any obsession to give the fullest possible West European picture, but because the rather special Scandinavian genetic make-up, with its mixture of East and West European inputs, can be used to understand and pinpoint Scandinavian intrusions during the later British prehistoric and historical periods. It seems from their maternal lineages that although northern Scandinavians – Finns and Saami – subsequently received much of their male genetic heritage from Eastern Europe, the very first Mesolithic immigrants may have belonged to the Atlantic coastal set from southern France and Spain.