The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (12 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

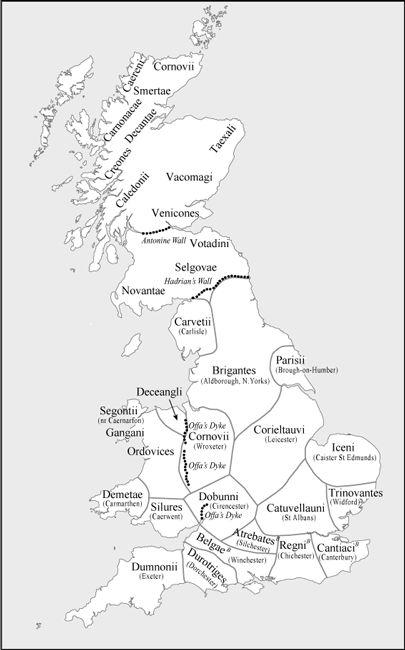

Figure 2.3

Ancient British tribal names, locations and capitals. The tribes between Dorchester and Canterbury all had connections with the Belgae (‘B’ on map); the ‘Belgae’ and ‘Atrebates’ even shared tribal names. In addition to the Roman defence walls (Antonine and Hadrian’s), Offa’s Dyke is shown, since it has been claimed to have been based partly on a previous earth defence rampart built by the Roman emperor Severus at the beginning of the third century

AD

.

Although connections have been and still are made between the Carvetii and their neighbours, the Brigantes, the evidence is indirect. The Brigantes were also a putative Celtic people and much the largest tribal grouping of northern England. They occupied most of England north of the Rivers Humber and Mersey that was not occupied by either the Carvetii on the west or the Parisii in East Yorkshire.

Much is known about the Brigantes’ interactions with the Romans, for whom they were generally a collaborating client tribe. They had a queen, rivalling Boudicca in fame, who feigned to shelter the fleeing rebel leader Caratacus and then promptly handed him over to the Romans in chains. They had a Roman capital at Isurium Brigantum (Aldborough, North Yorkshire). However, the Celtic claims rest mainly on their distinctive tribal name, which, having a celtic derivation, was shared with

various other contemporary tribes also thought to be Celtic. The derivation of the name may be from the Celtic mother-goddess Brigit, also known as Brigantia. Ptolemy mentions in his

Geography

three tribal locations with this name, one in northern England, another in south-east Ireland and Brigantinus Portus of the northern Gallaeci tribe. Also known as Brigantium Hispaniae, this was the ancient seaport of La Coruña in northwest Spain and the western terminus of a major trade route in tin, gold, lead and silver.

25

There was also a clutch of similar place/tribal names connected with Lake Constance on today’s Swiss/Austrian border. The people of Central Raetia were called the Brigantii. Their tribal capital was Brigantium Raetiae (now Bregenz), and Lake Constance itself was then called Brigantinus Lacus.

26

John Collis has an interesting map on which he shows the relevance of such

Brigant-

name links between the Continent and various parts of the British Isles. He assigns three levels of relevance: accepted, possible and rejected. He seems to accept the name link between the south-east Irish and English Brigantes tribes,

27

which would tend to favour the ‘celtic-speaking’ label as well as ‘Celtic’, since there is no lexical evidence for any non-celtic ancestral languages in Ireland. However, he implies, reasonably, that such a general name may lack tribal specificity. The Roman town name Cambodunum, however, does appear in both the northern English and west-Austrian locations, implying that the sharing of the root ‘Brigant-’ is more than just a coincidence.

The story of the British Brigantes does not stop there, since such a general label may have been supplied to the Romans, as a tribal description, by celtic-speaking informants, without the

tribe necessarily being celtic-speaking. The English historical linguist Kenneth Jackson, in his classic

Language and History in Early Britain

,

28

has a whole appendix on the problematic name used by Bede and others for the northernmost ‘Anglian’ tribe of Anglo-Saxon Britain, the Bernicii, who inhabited Bernicia on the east coast of North umberland. Although he opposes the idea, Jackson shows that the name could be derived through Welsh from the tribal name Brigantes. As he points out:

if Bede’s

Bernicii

… really represents a British tribe-name borrowed for the designation of the northernmost Anglian settlers, it can hardly have been taken over any later than the seventh century … it is plain that it had become … recognised by the Britons as now an English and not a British name, before c.600.

29

The paradox of Welsh writers naming a northern ‘invading Germanic-speaking tribe’ by the name of the British tribe they wiped out,

and

calling them English, can be resolved if the original Brigantes of the north country were not celtic-speaking, and were not really wiped out – merely invaded by new elites from Scandinavia. There is also the problem that the celtic stem

brigant

- (meaning ‘high person’ or ‘high place’) was used alternately to mean highlanders or people of the goddess Brigit. The former could simply be a description of terrain, the latter of religion.

Interestingly, Collis seems less completely convinced of the ‘possible’ celtic link between the Parisii of Yorkshire with their namesakes the Parisii of northern Gaul, who gave their name to the modern French capital. The former appear to have left some very unusual cultural remains, unique in the British Isles,

but with links in northern France and Belgium. The Continental Parisii, like other tribes of England twinned by name across the English Channel, such as the Atrebates and Belgae, were situated mainly north of Caesar’s politico-linguistic boundary between the Belgae of northern Gaul and his ‘celtic-speaking Gauls’ to the south of the Seine. Admittedly, the Parisii were only just to the north of the Seine. I shall come back to the Parisii later on, but for the moment I wonder whether there is a strong reason to argue that they were, to borrow Caesar’s classification, Celtic rather than Belgic.

Collis also puts the Damnonii of Ayrshire and the celtic-speaking Dumnonii of Cornwall into the category of ‘possible’ tribal name-links. Since there are surviving elements of Brythonic celtic language in both locations, this link could be promoted to a ‘probable’.

The only other such external name-link that Collis allows for Romano-British tribes in the island of Britain is that between the Atrebates of Belgica and the Atrebates of the English south. When the Romans invaded in

AD

43, the Atrebates already occupied a territory which covered Sussex, Hampshire, Berkshire, west Surrey and north-east Wiltshire. On the other side of the Channel, the Gallic Atrebates were situated well into northern Gaul; in other words they were Belgic and, in spite of what Collis says, possibly non-celtic-speaking. Collis accepts the name-twinning of the Atrebates across the Channel, but strangely not that of the tribe that actually carried the name Belgae. The English Belgae were close neighbours of the Atrebates and had their capital at Winchester (Venta Belgarum, ‘Market of the Belgae’). It is not clear why Collis chose to indicate the Atrebates link but not the equally general Belgic one. They are equivalent

in some respects, both having general meanings in their celtic derivations: ‘Atrebates’ means ‘settlers’, and ‘Belgae’ ‘people from Belgica’. But these names may have been labels imposed by Celtic informants, so neither of these links can be taken as proof that the respective tribes were necessarily either Celtic or celtic-speaking, since even Caesar does not suggest this (see discussion on Belgae and Atrebates in

Chapter 7

).

There is another English tribal name-link which Collis does not mention, the Cornovii. These people lived just on the east of the northern Welsh border in Staffordshire, Shropshire and Cheshire, with a regional capital at Wroxeter (Viroconium). They shared their name with a tribe, recorded by Ptolemy, in the northern tip of Scotland. It is not clear whether this is a coincidence, since the name could simply mean, in Latin, ‘people of the horn’. However, they both share one characteristic with all the western regions of Roman Britain, which were most likely to have been celtic-speaking: the absence of coinage at the time of the Roman invasion.

Coins are useful archaeological date and culture markers, for many reasons, but for our purposes they are useful in the negative sense. At the time of the Roman invasion,

most

of southern England, excluding Cornwall and the West Country, already both made and used coins (

Figures 2.2

and 7.3). Along with many other cultural features of the pre-Roman south of England, this practice – and indeed many of the imported coins – derived mainly from the rebellious northern Gallic region of the Belgae rather than from Caesar’s celtic-speaking part of Middle Gaul. Unfortunately, rulers’ short-form names inscribed on the coins

give little more information than is already available in the contemporary literature.

In contrast to the practice in southern England, none of the other tribes I have mentioned so far – the Welsh tribes, the Cornish Dumnonii, the Carvetii, the Brigantes, the Cornovii – made or used coins at that time. This penury also applied to Ireland and Scotland, suggesting that, in the British Isles, the lack of coins in Roman times was associated with the survival of celtic language after the Romans left (

Figure 2.2

).

While this difference between southern England at the time of Caesar and the rest of the British Isles could simply have been a random geographical association, it is reflected in reverse by the near-total absence of celtic language to be found in stone inscriptions in the same areas of England set up either during or after the Roman occupation (

Figures 2.2

and

7.4

). In contrast, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland, and to a lesser extent Scotland, have a rich record of inscribed stones attesting to their celtic-language heritage from soon after the Romans left.

30

The main positive evidence for celtic-language use in Roman England comes from linguistic research into place-names of Roman Britain and personal and tribal names cited in contemporary documents and on tablets and coins.

31

Although there is clear evidence for some celtic-derived names in Roman England from all these different sources, their relative frequency compared with equivalent parts of the rest of the Roman Empire (only 34% in England according to one study – see

Figure 7.2

32

) does not give the sort of overwhelming endorsement required for confidence in a 100% celtic-speaking England. (This concern is acknowledged in recent critical studies

33

; I shall discuss this evidence in more detail in

Chapter 7

.)

So to summarize, the West Country, Wales and northern England were home in large part to tribes for which there is some evidence for a celtic-language link: the Brigantes and Cornovii through their names, and the Welsh tribes, the Cornish Dumnonii and the Carvetii through surviving celtic-linguistic substrata and a presumed connection with the Brigantes during Roman times. For the tribes of the south coast of England, of whom the Roman historians had most to say, there is less evidence for Celtic culture or name, or for celtic-language use.

I have mentioned living evidence for Brythonic celtic being spoken in Brittany, Wales, Cornwall, northern England and southern Scotland, but there are claims that Brythonic was previously spoken throughout Scotland (by the Picts), and even in Ireland.

The Picts, supposedly painted, aboriginal tribes of northern Scotland, have always been a problem to place, since whatever language or languages they originally spoke have apparently disappeared except for a few scraps of evidence. They seem to have been linguistically replaced at least in western Scotland by Scottish Gaelic and ultimately by English during the first millennium

AD

. Scottish Gaelic was spoken by people of the Irish Dalriadic kingdom, thought to have invaded from Ireland in the fifth century

AD

– although, as we shall see below, there is more than one opinion on their time of arrival.

A number of theories have been put forward as to what language or languages the Picts spoke, and argument still continues, but a careful article written as long ago as 1955 by Kenneth Jackson still covers most and rejects quite a few.

34

The main problem is the lack of direct evidence of almost all kinds used in language reconstruction, such as texts or surviving linguistic remnants, which could be used to compare with place-names. Even celtic inscriptions, which are so useful in attesting to celtic language in other non-English parts of the British Isles, are absent in a large part of the areas supposedly occupied by the Picts.

The Medieval author Adamnan wrote in his

Life of St Columba

(completed around

AD

692–7)

35

that Columba used an interpreter to converse with the Picts. Presumably this meant that they spoke a different tongue from Columba’s, which was Irish Gaelic. Since Scottish Gaelic is similar to Irish Gaelic, that would tend to exclude Gaelic, unless Pictish was a particularly archaic form.