The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (31 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 5.5a

Almost the entire Neolithic expansion of Irish male gene lines was indigenous, coming from a sub-cluster of Rory (R1b-14a) and spreading across to Argyll. Another indigenous sub-cluster (R1b-15b) expanded nearby, in north Wales (composite of R1b-14a and R1b-15b).

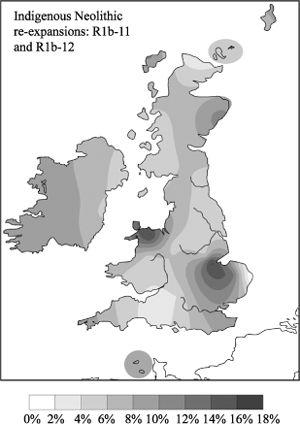

Figure 5.5b

Re-expansions, in the Fens and north Wales, of the related clusters R1b-11 and R1b-12, whose ancestor arrived in the Mesolithic (composite of R1b-11 and R1b-12).

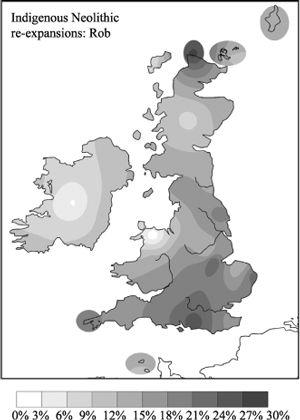

Figure 5.5c

The main indigenous re-expansion in Britain occurred in the large Rob cluster (R1b-8) and his small brother (R1b-7), whose common ancestor arrived in the Mesolithic. Although their highest frequencies are in eastern and southern Britain and Scotland, they cover nearly the whole of the British Isles (composite of R1b-7 and R1b-8).

I mentioned in

Chapter 4

the large British cluster Rob (R1b-8), who is another Mesolithic entrant with later Neolithic expansion. Rob is defined by one root type, which is the third most frequent founder type from Spain in Europe. Found in 16% of men of Valencia, this is the Frisian Modal haplotype (FMH).

53

While along most of the Continental Atlantic coast the Atlantic Modal Haplotype founder is generally the most common single Ruisko (R1b) type, Frisia has a rather higher frequency (17%) of FMH. In the British Isles the Rob cluster as a whole is only slightly less common (13%), but much more diverse than in Frisia (20%) (

Figure 5.5c

).

While the FMH and a common derivative with a single mutation difference

54

characterize Frisia in particular, they are nearly as common in eastern and southern Britain, where there is more

diversity. There are two other closely related gene types in the Rob cluster, which are more specifically limited to the British Isles. The Rob cluster occurs generally throughout the British Isles, being more common in eastern Britain (

Figure 5.5c

), including England and north-eastern parts of Scotland. It has its highest frequency, however, in Durness (37% of Ruisko, 27% of total).

55

Rob, along with his small descendant cluster R1b-7,

56

both re-expanded during the Neolithic (respectively 4,700 and 4,000 years ago). These two Neolithic lines, which derive from an Iberian founder with its highest frequency in Valencia, numerically contribute a large part of the apparent similarities between Frisia and England, but the distribution and diversity patterns are more consistent with parallel founding events than with a Frisian invasion, recent or otherwise.

Overall, these five indigenous Ruisko lines (R1b-7, 8, 11, 12 and 14) contribute, by their Neolithic re-expansions, 19% of extant British male lines.

57

There are two Ivan (I) gene groups, which I mentioned when discussing the Mesolithic, that are good local candidates for post-glacial recolonizations of Northern Europe. These are Ingert (I1c)-and Ian (I1a). Before focusing on their contribution to the British Neolithic, I suggest again that the Ivan gene group as a whole represented Northern Europe’s main internal migrating male Mesolithic–Neolithic component. Ivan makes the largest non-Iberian contribution to the British Isles (16% of all males), in particular in England, where it is most common (

Figure 3.7

). The ancestral Ivan root is generally accepted to

have originated in Europe before the LGM.

58

My estimate puts it back in the very Early Upper Palaeolithic;

59

subsequently, Ivan spread over Europe. But that is not the whole story, nor is the trail of the Ivan subgroups straightforward.

The main three post-glacial gene groups of Ivan found in Western Europe are Ian, I1b and Ingert. In my analysis, they all ultimately root to the period around the LGM.

60

As I explained in

Chapter 4

, the expansion of Ivan subgroups into Western Europe took place most likely at various times after the LGM, with Ingert and Ian moving up the Dnepr and Danube to the north-west and I1b2 along the north coast of the Mediterranean.

61

Ingert and Ian expand most strongly in the north-west during the Mesolithic and Neolithic, respectively (

Figures 3.8

and

4.11a

). The I1b* cluster concentrates in the Balkans and Moldavia at frequencies of 20%–40%, also spreading west to southern Italy, where it most probably gave rise to a new cluster ‘I1b2’ during the Late Mesolithic (see

Figure 5.6

).

62

On this basis, Ivan would have been confined mainly to southeast Europe, sheltering in the Balkans refuge throughout the LGM.

63

The restricted immediate post-LGM Balkans location would place the source and highest frequency of Ivan subgroups at centre of the oldest European Neolithic cultural zone, including the Starcevo, and allied Balkan Neolithic cultures, Krs, Cris and Karanovo.

64

As mentioned above, Ingert may have been the first Ivan subgroup to move up to north-west Europe, just before the YD, later re-expanding during the Mesolithic (

Figure 3.8

).

65

Several other Ivan subgroups date to around 8,000 years ago, which corresponds to estimates of population expansions within each of the Ian and I1b subgroups.

66

This provides a Balkan geographical origin of I1b* and an explanation for the Italian birthplace and movement west of I1b2 along the Mediterranean coast 8,000 years ago, for Ian up the Danube to Germany 8,800–6,800 years ago, and for I1b* north-east to Russia 7,000 years ago.

67

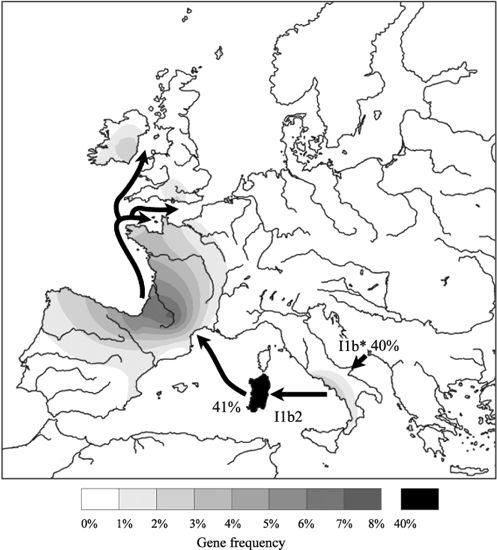

Figure 5.6

Migration of male line I1b2 from southern Italy to the British Isles via Sardinia and France during the late Mesolithic and early Neolithic.

Not only does a Balkan homeland for Ivan fit the oldest Neolithic location in Europe, but it also ties up geographically with the early archaeological origins of the LBK cultural

expansion from its homeland in the adjacent region of Hungary 7,500 years ago.

68

However, in this case Ingert would have been in the vanguard, moving up the Danube and Dnepr towards Germany and Poland mainly during the Mesolithic, followed by Ian mainly during the Neolithic. These two branches, however, are numerically much more important than the south-western branch I1b2, accounting for 20–40% of male lines in north-west Europe and more than filling in the Neolithic ‘Y gap’ posed by Martin Richards.

I1b* seems to have stayed localized to south-east and Eastern Europe, concentrating in the Balkans and Moldavia, where its expansion dates to over 7,000 years ago, consistent with the Balkan Neolithic. From there, I1b* also strayed north of the Black Sea towards the Ukraine and Russia. The smallest branch of all, I1b2, appears to have originated the other side of the Adriatic Sea in Italy, and moved west along the north Mediterranean coast via Sardinia around 8,000 years ago,

69

about the same time as Cardial Ware pottery and the Late Mesolithic.

Gene group I1b2 is found at its highest diversity and frequency (41%) in Sardinia, presumably as the result of an early founding settlement, but also extends along the Riviera into the Basque Country (6%) and Bearnais (south-west France) at 7.7%, spreading round the Bay of Biscay, again matching the spread of Cardial Ware. I1b2 is rare elsewhere, although found in the Pyrenees, Spain and notably in Normandy (2%), the Channel Islands (3%), northern Wessex and eastern Ireland (1%), where my dates suggest a Late Mesolithic presence, though Early Neolithic is also possible.

70

The age and distribution of I1b2 in the Mediterranean, southern France and northern Spain not only makes it an

interesting analogue for the spread of Cardial Ware pottery in the Late Mesolithic, but could also make it one of the several human genetic spreads in the Mediterranean, that could be putative vectors for Celtic languages. Although the date could be a little early, the ultimate origin of I1b2 in the Balkans and the Italian connection fits with Celtic associations with Germanic and Italic languages on the Indo-European family tree (see Figure 6.2). If the analogy held water, however, it would tend to confirm the very small gene flow associated with the Atlantic spread of Celtic languages to the British Isles, even then only affecting the southern part. We shall look at E3b and J2, two other possible male genetic candidates for the Mediterranean-Atlantic Odyssey shortly, after first tracing a northern Ivan branch: ‘Ian’.

Given the Neolithic expansion ages for Ian and his sub-clusters in Western Europe and Britain, when we look in more detail we find that he could adequately fulfil the role of the main northwestern expanding Early Neolithic line, in both distribution and dates. A trail up the Danube from Hungary can be discerned in the distribution of Ian in the Balkans and Central Europe (

Figure 4.11a

).

71

As mentioned, however, although common in northwest Germany, by far Ian’s highest frequency is in Denmark and the adjacent areas of southern Scandinavia. The latter regions are rather farther north than is usually associated with the spread of LBK pottery, which is thought to be the trademark of the northern Early Neolithic. In spite of this, early LBK does have cultural parallels and there is evidence of interaction between LBK settlements and the northern region, including Denmark.

72

The very high frequency of Ian in southern Scandinavia could indicate a founder event.

In north-west Europe, Ian did not confine himself to Germany and Denmark. Like Ingert, he spread to occupy roughly the present distribution of Germanic languages – that is, southern Scandin avia (e.g. Denmark 37%), Germany (25%), Holland (16.7%), Switzerland (5.6%) and England (10–32%). The British distribu tion is particularly interesting, since it excludes most of Wales – and largely misses Ireland. In addition, Ian is also found in France, although favouring the north, particularly Caesar’s Belgic Gaul (23%) and Normandy (at 11.9%), rather neatly fitting the ultimate spread of LBK pottery (

Figures 4.11a

and

5.1

).

73