The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (23 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 4.3

Mesolithic settlements on the south coast of England. There is evidence for long-distance movement of raw materials across southern England and Cornwall.

In its striking and rich ‘novelty’ the Mesolithic of the Atlantic coast is analogous to the unique and much more recent and famous non-agricultural, fishing cultures of the wet temperate coasts of the Pacific coast of North America (Washington State, British Columbia and Alaska) with their advanced maritime skills and complex artistic-spiritual life.

I recently had the privilege of visiting and staying with some of the surviving communities of this culture, on the coast of British Columbia in Canada. Although ravaged and nearly annihilated by smallpox after first European contact and then having had their ritual culture objects and practices – totem poles, potlatch meetings, and so on – comprehensively burnt and outlawed by colonists and missionaries, sufficient stragglers had remained

to pull together an existence under their animal totem clans, such as the whale, the bear, the eagle and the raven. The Haida of Queen Charlotte Island lost less of their cultural inheritance than most and are now a famous tourist attraction.

The people I visited farther south, accessible only by ferry and then by aluminium speedboat, had lost everything, culture and sacred objects together, in the missionary-imposed iconoclastic holocaust. Today they are still squatters in their own territory, since no treaties to establish reserves were ever made. What they had not lost, however, was their ability to survive on a thin rim of coast sandwiched between the forest and the sea, without becoming farmers. The hinterland of the coastline is dense, impenetrable temperate rainforest with a range of wonderful flora and fauna, including bears. But they still manage to live off the beach and the sea, and, if given the chance, might be better custodians of the vanishing salmon stock than the joint interests of the Canadian Government and the fishing companies.

The Atlantic Mesolithic coastal foragers had careful burial rituals – often in close association with their large shell middens. The quality and richness of grave goods, from small personal ornaments to elaborately carved antlers and the use of ochre, could indicate variation in status, but their presence all along the coast also suggests common belief systems spread over the whole region.

8

One intriguing, presumably coincidental echo of the Pacific coast of British Columbia was found at Stonehenge during an excavation to extend the car park there. A set of post-holes, dating to over 9,000 years ago, had previously held three very large pine trunks each nearly a metre in diameter. They predate the famous stone circles by some millennia:

These three timbers (and there may be more) represent the first truly monumental structure of the Mesolithic period known to us. What form they took (carved totem poles perhaps?) and the reason for their erection we will never know, but the Stonehenge timber alignment is unlikely to be unique.

9

The thaw after the Younger Dryas (YD) and its cultural counterpart, the European Mesolithic, was a springtime of environmental rebirth and cultural efflorescence after the long shadow of the last Ice Age. Archaeological clues give evidence for a dramatic increase in human activity in Northern Europe heralded by the thaw, although the peaks of archaeological activity did not quite match those seen in the brief and lesser thaw before the YD. It is reasonable, however, to suppose that populations in Northern Europe expanded during the Mesolithic. In addressing the genetic record, I shall be asking how much of the expansion was among indigenous lines already present from before the YD, how much was from immigration from elsewhere in Europe, from where it came, and to where, in the British Isles, it went.

Since the archaeological/cultural message is ambivalent on the extent of south-to-north coastal migrations during the Mesolithic, we might expect a relatively stable genetic picture for this climatically welcoming period in north-west Europe. This ambivalence has been shared by mtDNA specialists. When we look at the potential for a post-YD Mesolithic intrusion into north-west Europe, and more particularly the British Isles, we

do however find fresh gene lines, again deriving from the Iberian Peninsula. Dealing first with maternally transmitted genes (i.e. mtDNA), I have already mentioned Martin Richards’ founder analysis of identifiable Near Eastern contributions to the modern maternal gene pool in Europe (see p. 122). Richards showed that about 11% of modern types arrived in the Mesolithic. Although this is a larger proportion than is accounted for by later immigrations, it would still have been only about a fifth of that attributable to the Late Upper Palaeolithic (LUP), just before the YD.

Clearly, each era brought people who were ancestors for the next, and only a minority of ‘farmers’ ancestors’ actually arrived during the Neolithic. Instead, the earlier Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic colonizations of the British Isles brought many of the ancestors of people who would become farmers later during the Neolithic. Ireland has a much lower component of putative Neolithic gene lines than other parts of Europe, suggesting even less dilution during the Neolithic and a relatively greater contribution of LUP and Mesolithic gene lines to modern peoples.

10

I think that the figure of 11% for Near Eastern contributions to the modern European maternal gene pool during the Mesolithic underestimates Basque gene flow. Also it depended on factors, unknown in 2000, when Richards and his colleagues published their analysis, which affected the apportionment of founding lines to before or after the YD.

11

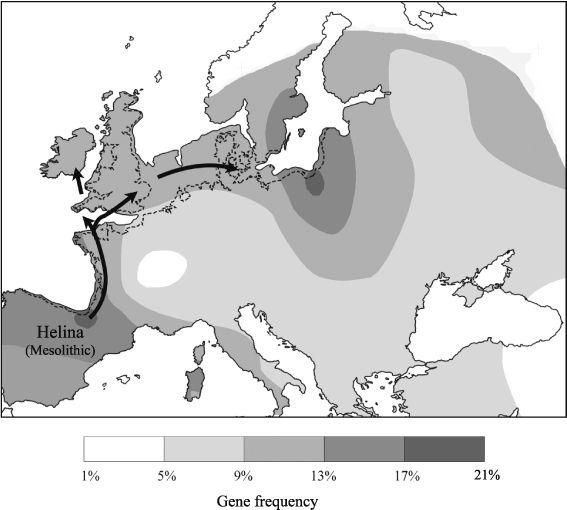

A subsequent reanalysis has described a number of new subgroups of the Helina (H) lineage. Their ages and distribution suggest that some of these subgroups may have spread along the Atlantic coast during the Mesolithic period immediately after the YD. In total, four of these possible Mesolithic Helina subgroups (H2, H3, H4 and

H5a) account for 11% of Irish and 11% of maternal lines in the UK in general. Subgroup H3 is notable here, since it dates to around 9,000 years ago and by itself contributes 7% to the Irish gene pool – a figure two-thirds higher than in the UK.

12

There are other specific gene groups, T, T2 and K, whose estimated age brackets straddle the period of the Younger Dryas and are found in both Iberia and western Britain, including Cornwall.

13

Overall, the reassignment of these small gene groups to the Early Mesolithic could increase the maternal Mesolithic immigrant component by a further 10% at the expense of lines coming in during the Late Upper Palaeolithic, making a total maternal Mesolithic intrusion of around 22% (

Figure 4.4

). But however you decide to allocate these arrivals among the YD, the LUP and the Mesolithic, the result is that these early prefarming Atlantic coastal re-expansions would still between them contribute more than half of today’s maternal lines.

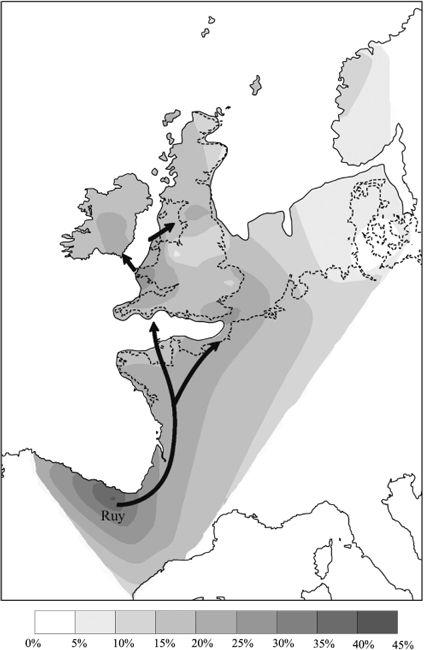

When I started looking at the Y-chromosome tree, I could see clear evidence for a large pre-Neolithic intrusion of new Ruisko (R1b) clusters to the British Isles from Iberia after the YD. Certain Ruisko clusters predominate in different regions of the British Isles, but it is important to try to date specific ones to a particular period (e.g. pre- or post-YD, or even later).

The post-YD element is made up of nine Ruisko clusters (R1b-1 to 3, R1b-7, R1b-8 and R1b-10 to 13), which include, and all derive from, the new major Mesolithic gene cluster,

Ruy

(R1b-10). These clusters expanded at various times from the Mesolithic onwards. Ruy is a Basque name; the cluster derives from Iberia, and dates overall to around 11,500 years ago (

Figure A4

in Appendix C). Although Ruy’s ancestor Rox (R1b-9) arrived in the very Early Mesolithic, not all nine descendent clusters expanded simultaneously at that time. Some (such as R1b-7, R1b-8, R1b-11 and R1b-12) re-expanded from common Mesolithic ancestors, but did so during the Neolithic and later (see the next chapter). The Ruy cluster arises as a one-step derivative of Rox (i.e. it differs by one mutation). Ruy’s core or root gene type is also known as the

Atlantic Modal Haplotype

(AMH), since it is by far the most common single Y gene type in Western Europe, accounting for 18% of British and 19% of Basques in the dataset I am using.

14

Figure 4.4

Maternal gene flow into the British Isles during the Mesolithic. Gene flow follows the European coastlines, and a founder effect is seen at the end of the trail in the Baltic. (Combined gene frequency of Helina Mesolithic sub-groups H2, H3, H4 and H5a in Europe – arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography. Contours follow greater land area resulting from low sea level.)

Ruy’s distribution is subtly different from that of his closely related forefather Rox from before the Younger Dryas. Not surprisingly, the ubiquitous Ruy is now found in all thirty-one British and all but one of the thirteen Continental population samples studied. However, in terms of relative frequency there is a bias to the parts of the Western Atlantic façade and the south coast of Britain missed by Rox in the first migration before the Younger Dryas freeze-up (

Figure 4.5

). By Ruy’s time the Irish Sea was open, St George’s Channel had already split southern Ireland from St David’s Head and Haverfordwest in south-west Wales, and the Channel, although not quite open at the start of the Holocene, was occluded by just a narrow strip and soon opened up. All the now familiar features of the southern coastline of the British Isles today were beginning to take shape, and the coast became as accessible for settlement as it is today.

Local Ruy frequency favours the Welsh coast at 28–29%, and Cornwall, the Channel Islands, the south coast and Norfolk at 17–27% in order of increasing frequency (

Figure 4.5

).

15

In Llangefni in north Wales, for instance, 26% of males belong just to the single core gene type AMH.

16

This contrasts with Rush, near Dublin just across the Irish Sea, and the Gaelic-name sample, where males carry rather less of this type, at 10.5% and 18%, respectively.

17

Even parts of Scotland and Ireland, which had missed out on Rox the first time round, had a higher dose of Ruy. So, Castlerea in the centre of Ireland and the Western Isles of Scotland received 26% and 22% Ruy, respectively.

18

Figure 4.5

Ruy, the main male gene cluster moving into the British Isles during the Mesolithic from 11,500 years ago. Ruy (R1b-10) is the largest Ruisko cluster and the main source of gene flow from the south-western refuge for that period. The gene flow follows the ancient extended Atlantic coastline, which had by now opened up to show the southern part of the English Channel (arrows indicate direction of gene flow based on the gene tree and geography.)

So we find Ruy dominating the parts that Rox had not, on a first come, first served basis; so much so, that the sample sites with higher rates of the first-comer Rox in the British Isles are associated with lower rates of Ruy, and vice versa. The earlier lack of access to Northern Europe, immediately after the LGM, for the beachcombing Rox would no longer have been such a problem for Ruy with the new coastline changes. Consistent with this selective sea level access hypothesis, rates for Ruy across the North Sea, although lower than in Britain, are considerably higher at 7–13% than for Rox (2–5%).