The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (59 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

Figure 12.3a

The largest Viking gene cluster, I1a-3, arose in Bergen, Norway in the Bronze Age. The British founding I1a-3 cluster dates to 1,200 years ago and is found in all regions visited by the Vikings in Britain, including York (11%), Norfolk (11%), the Western Isles (7%) and the west coast. Additionally there was a strong founder effect in Iceland (22%).

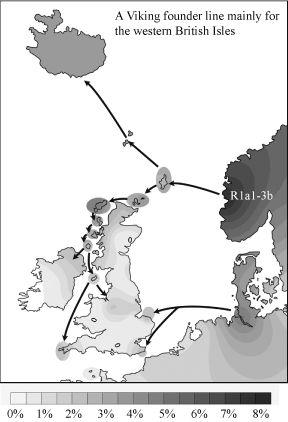

Figure 12.3b

Gene cluster R1a1–3b also arose in Bergen in the Bronze Age and arrived in the British Isles within the last 2,000 years, settling mainly in the Western Isles (5%), and to a lesser extent in Shetland (2%), Orkney (3%) and other parts of the western British Isles.

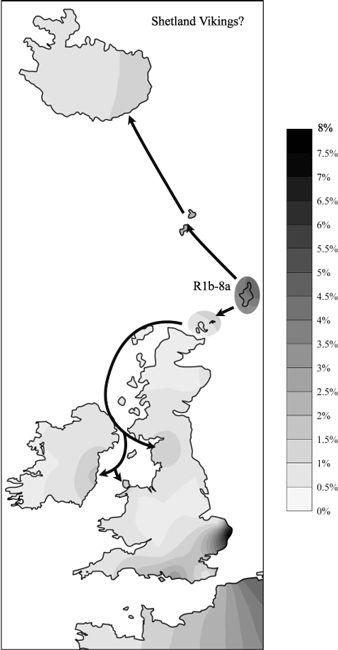

Figure 12.3c

Gene cluster R1b-8a is a uniquely British male cluster found in Shetland and Norfolk and does not derive from northern Europe. He appears to have expanded down the west coast of Britain and also ultimately to Iceland, as if he were a Viking.

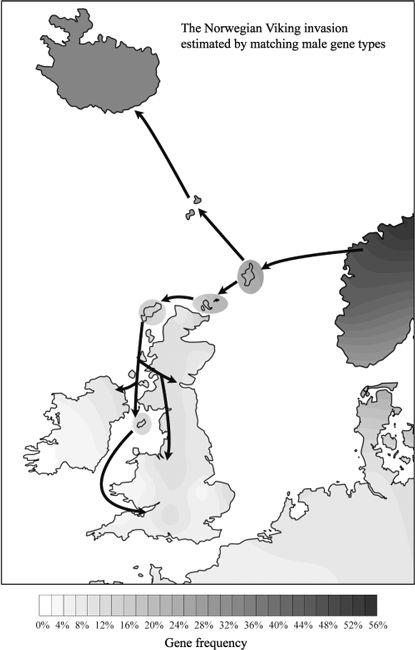

Figure 12.4

Matching male gene type intrusions from Norway. These are found in typical Norwegian Viking locations, in Shetland (20%), Orkney (17%), and the Isle of Man (10%), and at rates of 7–8% down western Britain and in Northern Ireland. 33% of Icelandic male genes have matches in Norway.

Julian Richards, the archaeological presenter for the BBC documentary

Blood of the Vikings

, eloquently described the general difficulty of finding enough physical traces of Vikings to match history’s horror stories and estimate the impact experienced by the British. As he pointed out, part of the reason was that they left little in the way of non-perishable remains, although there were many settlements. But in spite of the physical silence, place-name and linguistic evidence is abundant (

Figures 12.1

and

12.2

). The Norwegians, like the Danes, did leave their genetic mark with its strongest traces in the most vulnerable of the western British Isles and in the northern islands of Scotland.

The male genetic group markers most clearly linked to Norway, in particular Trondheim in the north, belong to the more eastern European gene group R1a1, or Rostov (

Figure 4.10

). Five of Rostov’s descendent sub-clusters date to the Bronze and Neolithic Ages and earlier, and are represented in eastern Britain, East Anglia, the Isle of Man, and Scotland and its northern islands (the Western Isles, Shetland and Orkney). The two Norwegian Bronze Age clusters in this group focus more specifically, one in Shetland and Orkney and the other on

the Isle of Man

12

(

Figure 5.15a,

Chapter 5

, and Appendix C). Only one Rostov cluster, R1a1-3b, dates to anywhere near the historical Viking period.

13

Coincident with known locations of Norwegian Viking raids, R1a1-3b is found most in the Western Isles and in Shetland and Orkney, as well as locations in Western Scotland, the Isle of Man and north-east Ireland (

Figure 12.3b

). Based on this division in dates between the Bronze Age and Neolithic on the one hand, and the time of the Viking raids on the other, only 17.5% of the R1a1 lines (1% of extant British lines) would have arrived in the British Isles during the Viking period.

14

Although this may be an underestimate, and the true figure may be as high as 2%, it underlines how easy it is to overestimate high-profile historical migrations from the Continent when there were multiple migrations from the same source at earlier dates.

Having dealt with the first two of the three British male genetic cluster expansions from the historical period, I should mention that the third Dark Ages founding cluster is the biggest surprise. It cannot in any way be identified with the nearby Continent across the North Sea, or with a recent founding event from Iberia. In the context of the Dark Ages, it was actually an indigenous re-expansion and should not really be called a founding cluster in the British context. This is cluster R1b-8a, which is a sub-cluster of Rob, who arrived in northern and southern Britain during the Mesolithic (

Chapter 4

) and re-expanded during the Neolithic (

Figure 5.5c

) and ultimately derives from the Mesolithic Iberian male R1b-10 cluster (Ruy). The R1b-8a cluster is uniquely ‘off-Continent’ and characteristic of the far

north of Scotland. It appears to have expanded from Shetland to Iceland and down the western British Isles and nowhere else (

Figure 12.3c

).

15

In other words, these are ‘indigenous’ British male types spreading genetically as if they were Vikings, and maybe acting in the same way (Plate 21). The western British locations seem typical for the Viking spread and include Penrith in Cumbria, Llangefni in north Wales, Rush on the east coast of Ireland and also Dorchester and Midhurst on the south coast of England.

The implications of Shetland harbouring its own ‘indigenous British-Viking raiders’ are interesting. Of course, there are many Scandinavian male gene types in Shetland; this is well known, and Shetland is acknowledged to have been a major Viking outpost. However, in spite of the strong Norwegian influence, 64% of Shetland males have Ruisko types with a very local flavour, and 72% of all Shetland male gene types are ‘indigenous’ in the sense that they have no matches anywhere in north-west Europe.

16

Given the bellicose, male-dominated political structure of Medieval Scandinavian society, it is hardly likely that a local ‘Pictish’ chieftain would have been able to spread his seed so widely in the Scandinavian Atlantic maritime network of the north unless he was an equal member of the Viking culture.

Shetland and Orkney were the springboards for the Norwegian Viking colonization of Iceland, but it has always been somewhat puzzling why there should be so many British male and female gene types in Iceland. Icelandic geneticist Agnar Helgason and colleagues at Oxford University have carried out much of the work on this. Although one might expect Viking gene flow to be male dominated, a complex male–female interchange occurred between the Vikings and the British Isles. It includes a large

contemporary contribution from British Atlantic coastal females carried to Iceland and

outnumbering

the Norwegian maternal component there by a ratio of 2:1 today. The male contribution to Iceland from the British Isles was less and in a minority (1:4, British male lines:Scandinavian male lines). Yet even a 25% contribution by British males to the Icelandic genetic heritage still needs explaining.

17

The overwhelmingly female matches between British and Icelanders have usually been put down to male Vikings acquiring British women, either with their consent or as slaves. This view is based on mentions of slaves in early Icelandic records, though there are no exact records of numbers. Male British migrations to Iceland are another matter. It is difficult to use the male slavery story to explain the contemporary expansion of the Shetland R1b-8a male cluster down the west coast of Britain – by analogy, rather like taking coals to Newcastle. Iceland is supposed to have been colonized by northern Norwegians mainly from the Trondheim region. Yet on the database I am using, Iceland’s Scandinavian component has a gene group profile nearer to southern Norway (Bergen or Oslo) and Denmark, as a result of dilution with the historic founding cluster I1a-3 and the Ruisko group. Of Icelandic males, 37% have the Atlantic coastal Ruisko gene group.

18

This is significantly higher than Trondheim, which has only 29%.

19

In Iceland, the high preponderance of the more southerly male Viking gene cluster I1a-3 has several possible interpretations, the simplest of which is that there was a much larger southern Scandinavian component in these northern islands than has previously been assumed. For I1a-3 this means southern Norway, since there are hardly any exact Danish gene type

matches in Shetland and Orkney (only 3%), while there are plenty from Norway.

20

But that still does not explain the Ruisko contribution. I tested the additional possibility of British male influence through indigenous R1b (Ruisko) clusters. I found eighteen (13%) exact matches in Iceland for unique British indigenous gene types.

21

These matches, although they include the types I identified for the Shetland ‘indigenous Viking’ expansion, were not all derived from Shetland and Scotland, but from different locations around the coasts of Britain. My figure of 13% matches is likely to be an underestimate of British influence; Oxford geneticist Sara Goodacre and colleagues, who included Agnar Helgason, have recently estimated a 25% British/Irish male contribution to Iceland.

22

The indigenous Shetland male R1b-8a cluster expanded both down the British west coast and to Iceland around the time of the Vikings (

Figure 12.3c

). And as I have shown in earlier chapters, there were several Neolithic Scandinavian intrusions into Shetland, Orkney and Scotland. The implications of a significant British male involvement in the ninth-century colonization of Iceland from Shetland are therefore that, rather than being the unfortunate enslaved or slaughtered victims of a major Viking incursion, Shetland Islanders may already have been an established part of the show. Politically and culturally, they could have been vigorous participants in the Scandinavian world long before the Vikings set sail in the seventh century. There is circumstantial evidence suggesting that the advent of the Vikings could have been low-key ‘business as usual’. Cunliffe paints a picture of quiet continuity in the Shetlands during the Viking Age:

no centralized trading port has been identified [and] what exchanges there were (… timber was imported from Norway) would have been organized on a small-scale local basis, with the merchants visiting individual coastal settlements … Norse settlement was much like that of the early first millennium settlements it replaced. In some cases like Jarlshof on Shetland and Udal on North Uist, the same settlement sites simply continued in use. On the island of Rousay Viking burials were found in a cemetery which had been established centuries earlier, the Viking graves carefully avoiding the earlier burials that had been marked by boulders.

23

Consistent with the view of these islands as a stable part of the Scandinavian world, Orkney was also formerly a base for regular Viking raiding parties, as we read in the lifestyle of Svein Asleifarson recalled in the

Orkneyinga Saga

: