The New Penguin History of the World (29 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

This was teaching likely to produce men who would respect the traditional culture, emphasize the value of good form and regular behaviour, and seek to realize their moral obligations in the scrupulous discharge of duties. It was immediately successful in that many of Confucius’s pupils won fame and worldly success (though his teaching deplored the conscious pursuit of such goals, urging, rather, a gentlemanly self-effacement). But it was also successful in a much more fundamental sense, since generations of Chinese civil servants were later to be drilled in the precepts of behaviour and government which he laid down. ‘Documents, conduct, loyalty and faithfulness’, four precepts attributed to him as his guidance on government, helped to form reliable, sometimes disinterested and even humane civil servants for hundreds of years.

Confucian texts were later to be treated with something like religious awe. His name gave great prestige to anything with which it was associated. He was said to have compiled some of the texts later known as the Thirteen Classics, a collection which only took its final form in the thirteenth century

AD

. Rather like the Old Testament, they were a somewhat miscellaneous collection of old poems, chronicles, some state documents, moral sayings

and an early cosmogony called the Book of Changes, but they were used for centuries in a unified and creative way to mould generations of China’s civil servants and rulers in the precepts which were believed to be those approved by Confucius (the parallel with the use of the Bible, at least in Protestant countries, is striking here, too). The stamp of authority was set upon this collection by the tradition that Confucius had selected it and that it must therefore contain doctrine which digested his teaching. Almost incidentally it also reinforced still more the use of the Chinese in which these texts were written as the common language of China’s intellectuals; the collection was another tie pulling a huge and varied country together in a common culture.

It is striking that Confucius had so little to say about the supernatural. In the ordinary sense of the word he was not a ‘religious’ teacher (which probably explains why other teachers had greater success with the masses). He was essentially concerned with practical duties, an emphasis he shared with several other Chinese teachers of the fourth and fifth centuries

BC

. Possibly because the stamp was then so firmly taken, Chinese thought seems less troubled by agonized uncertainties over the reality of the actual or the possibility of personal salvation than other, more tormented, traditions. The lessons of the past, the wisdom of former times and the maintenance of good order came to have more importance in it than pondering theological enigmas or seeking reassurance in the arms of the dark gods.

Yet for all his great influence and his later promotion as the focus of an official cult, Confucius was not the only maker of Chinese intellectual tradition. Indeed, the tone of Chinese intellectual life is perhaps not attributable to any individual’s teaching. It shares something with other oriental philosophies in its emphasis upon the meditative and reflective mode rather than the methodical and interrogatory which is more familiar to Europeans. The mapping of knowledge by systematic questioning of the mind about the nature and extent of its own powers was not to be a characteristic activity of Chinese philosophers. This does not mean they inclined to other-worldliness and fantasy, for Confucianism was emphatically practical. Unlike the ethical sages of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, those of China tended always to turn to the here and now, to pragmatic and secular questions, rather than to theology and metaphysics.

This can also be said of systems rivalling Confucianism which were evolved to satisfy Chinese needs. One was the teaching of Mo-Tzu, a fifth-century thinker, who preached an active creed of universal altruism; men were to love strangers like their own kinsmen. Some of his followers stressed this side of his teaching, others a religious fervour which encouraged the worship of spirits and had greater popular appeal. Lao-Tse,

another great teacher (though one whose vast fame obscures the fact that we know virtually nothing about him), was supposed to be the author of the text which is the key document of the philosophical system later called Taoism. This was much more obviously competitive with Confucianism, for it advocated the positive neglect of much that Confucianism upheld; respect for the established order, decorum and scrupulous observance of tradition and ceremonial, for example. Taoism urged submission to a conception already available in Chinese thought and familiar to Confucius, that of the

Tao

or ‘way’, the cosmic principle which runs through and sustains the harmoniously ordered universe. The practical results of this were likely to be political quietism and non-attachment; one ideal held up to its practitioners was that a village should know that other villages existed because it would hear their cockerels crowing in the mornings, but should have no further interest in them, no commerce with them and no political order binding them together. Such an idealization of simplicity and poverty was the very opposite of the empire and prosperity Confucianism upheld.

All schools of Chinese philosophy had to take account of Confucian teaching, so great was its prestige and influence. A later sage, the fourth-century Mencius (a latinization of Meng-tzu), taught men to seek the welfare of mankind in following Confucian teaching. The following of a moral code in this way would assure that Man’s fundamentally beneficent nature would be able to operate. Moreover, a ruler following Confucian principles would come to rule all China. Eventually, with Buddhism (which had not reached China by the end of the Warring States Period) and Taoism, Confucianism was habitually to be referred to as one of the ‘three teachings’ which were the basis of Chinese culture.

The total effect of such views is imponderable, but probably enormous. It is hard to say how many people were directly affected by such doctrines and, in the case of Confucianism its great period of influence lay still in the remote future at the time of Confucius’s death. Yet Confucianism’s importance for the directing élites of China was to be immense. It set standards and ideals for China’s leaders and rulers whose eradication was to prove impossible even in our own day. Moreover, some of its precepts – filial piety, for example – filtered down to popular culture through stories and the traditional motifs of art. It thus further solidified a civilization many of whose most striking features were well entrenched by the third century

BC

. Certainly its teachings accentuated the preoccupation with the past among China’s rulers which was to give a characteristic bias to Chinese historiography, and it may also have had a damaging effect on scientific enquiry. Evidence suggests that after the fifth century

BC

a tradition of astronomical observation which had permitted the prediction of lunar

eclipses fell into decline. Some scholars have seen the influence of Confucianism as part of the explanation of this.

China’s great schools of ethics are one striking example of the way in which almost all the categories of her civilization differ from those of our own tradition and, indeed, from those of any other civilization of which we have knowledge. Its uniqueness is not only a sign of its comparative isolation, but also of its vigour. Both are displayed in its art, which is what now remains of ancient China that is most immediately appealing and accessible. Of the architecture of the Shang and Chou, not much survives; their building was often in wood, and the tombs do not reveal very much. Excavation of cities, on the other hand, reveals a capacity for massive construction; the wall of one Chou capital was made of pounded earth thirty feet high and forty thick.

Smaller objects survive much more plentifully and they reveal a civilization which even in Shang times is capable of exquisite work, above all in its ceramics, unsurpassed in the ancient world. A tradition going back to Neolithic times lay behind them. Pride of place must be given none the less to the great series of bronzes which begin in early Shang times and continue thereafter uninterruptedly. The skill of casting sacrificial containers, pots, wine-jars, weapons, tripods was already at its peak as early as 1600

BC

. And it is argued by some scholars that the ‘lost-wax’ method, which made new triumphs possible, was also known in the Shang era. Bronze casting appears so suddenly and at such a high level of achievement that people long sought to explain it by transmission of the technique from outside. But there is no evidence for this and the most likely origin of Chinese metallurgy is from locally evolved techniques in several centres in the late Neolithic.

None of the bronzes reached the outside world in early times, or at least there has been no discovery of them elsewhere, which can be dated before the middle of the first millennium

BC

. Nor are there many discoveries outside China at earlier dates of the other things to which Chinese artists turned their attention, the carving of stone or the appallingly hard jade, for example, into beautiful and intricate designs. Apart from what she absorbed from her barbaric nomadic neighbours China not only had little to learn from the outside until well into the historical era, it seems, but had no reason to think that the outside world – if she knew of it – wanted to learn much from her.

6

The Other Worlds of the Ancient Past

So far in this account huge areas of the world have still hardly been mentioned. Though Africa has priority in the story of the evolution and spread of humanity, and though the entry of men to the Americas and Australasia calls for remark, once those remote events have been touched upon, the beginnings of history focus attention elsewhere. The homes of the creative cultures which have dominated the story of civilization were the Near East and Aegean, India and China. In all these areas some meaningful break in rhythm can be seen somewhere in the first millennium

BC

; there are no neat divisions, but there is a certain rough synchrony which makes it reasonable to divide their histories in this era. But for the great areas of which nothing has so far been said, such a chronology would be wholly unrevealing.

This is, in the main, because none of them had achieved levels of civilization comparable to those already reached in the Mediterranean and Asia by 1000

BC

. Remarkable things had been done by then in western Europe and the Americas, but when they are given due weight there still remains a qualitative gap between the complexity and resources of the societies which produced them and those of the ancient civilizations which were to found durable traditions. The interest in the ancient history of these areas lies rather in the way they illustrate that varied roads might lead towards civilization and that different responses might be demanded by different environmental challenges than in what they left as their heritage. In one or two instances they may allow us to reopen arguments about what constitutes ‘civilization’, but for the period of which we have so far spoken the story of Africa, of the Pacific peoples, of the Americas and western Europe is not history but still prehistory. There is little or no correspondence between its rhythms and what was going on in the Near East or Asia, even when there were (as in the case of Africa and Europe though not of the Americas) contacts with them.

Africa is a good place to start, because that is where the human story first began. Historians of Africa, sensitive to any slighting or imagined slighting of their subject, like to dwell upon Africa’s importance in prehistory. As things earlier in this book have shown, they are quite right to do so; most of the evidence for the life of the earliest hominids is African, they spread from it into Eurasia and beyond, and the first humans in due course followed them. Then, though, in the Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic the focus moves elsewhere. Much was still to happen in Africa but the period of its greatest influence on the rest of the world is long over.

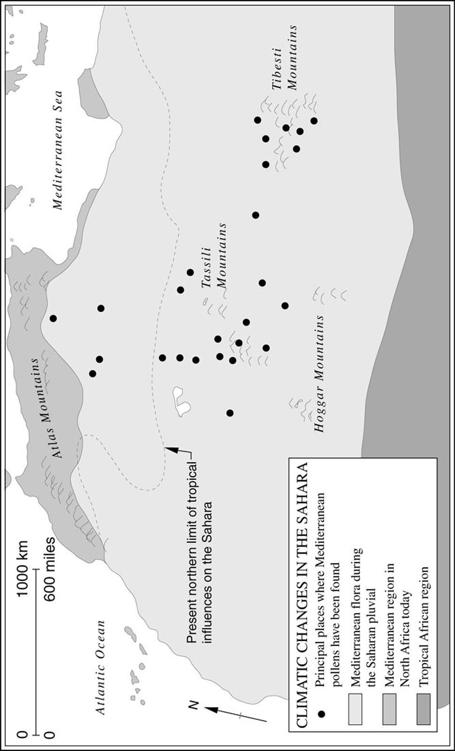

Why this is so we cannot say, but one primary force may well have been a change of climate. Even recently, say in about 3000

BC

, the Sahara supported animals such as elephants and hippopotami, which have long since disappeared there; more remarkably, it was the home of pastoral peoples herding cattle, sheep and goats. Today, the Sahara is the fastest-growing desert in the world. But what is now desert and arid canyon was once fertile savannah intersected and drained by rivers running down to the Niger and by another system 750 miles long, running into Lake Tchad. The peoples who lived in the hills where these rivers rose have left a record of their life in rock painting and engraving very different from the earlier cave art of Europe which depicted little but animal life and only an occasional human. This record also suggests that the Sahara was then a meeting place of Negroid and what some have called ‘Europoid’ peoples, those who were, perhaps, the ancestors of later Berbers and Tuaregs. One of these peoples seems to have made its way down from Tripoli with horses and chariots and perhaps to have conquered the pastoralists. Whether they did so or not, their presence (like that of the Negroid peoples of the Sahara) shows that Africa’s vegetation was once very different from that of later

times: horses need grazing. Yet when we reach historical times the Sahara is already desiccated, the sites of a once prosperous people are abandoned, the animals have gone.