The New Penguin History of the World (125 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The peace of 1763 did not in fact go so far in crippling France and Spain as many Englishmen had wanted. But it virtually eliminated French competition in North America and India. When it was a question of retaining Canada or Guadeloupe, a sugar-producing island, one consideration in favour of keeping Canada was that competition from increased sugar production within the empire was feared by Caribbean planters already under the British flag. The result was a huge new British empire. By 1763, the whole of eastern North America and the Gulf Coast as far west as the mouth of the Mississippi was British. The elimination of French Canada had blown away the threat – or, from the French point of view, the hope – of a French empire of the Mississippi valley, stretching from the St Lawrence to New Orleans, which had been created by the great French explorers of the seventeenth century. Off the continental coast the Bahamas were the northern link of an island chain that ran down through the lesser Antilles to Tobago, and all but enclosed the Caribbean. Within it, Jamaica, Honduras and the Belize coast were British. In the peace of 1713, the British had exacted a limited legal right to trade in slaves with the Spanish empire, which they quickly pressed far beyond its intended limits. In Africa there were only a few British posts on the Gold Coast but these were the bases of the huge African slave trade. In Asia the direct government of Bengal was about to provide a start to the territorial phase of British expansion in India.

British imperial supremacy was based on sea-power. Its ultimate origins could be sought in the ships built by Henry VIII, among the greatest warships of the age (the

Harry Grâce à Dieu

carried 186 guns), but this early start was not followed up until the reign of Elizabeth I. Her captains, with little financing available either from Crown or commercial investors, built both a fighting tradition and better ships from the profits of operations against the Spanish. Again, there was an ebbing of interest and effort under the early Stuart kings. The royal administration could not afford ships (and paying for new ones was, indeed, one of the causes of the royal

taxes Parliament had raged over). It was only under the Commonwealth, ironically, that the serious and continuing interest in naval power which sustained the Royal Navy of the future began. By that time, the connection between Dutch superiority in merchant shipping and their naval strength had been taken to heart and the upshot was the Navigation Act which provoked the first Anglo-Dutch war. A strong merchant marine provided a nursery of seamen for fighting vessels and the flow of trade whose taxation by customs dues would finance the upkeep of specialized warships. A strong merchant marine could only be built upon carrying the goods of other nations: hence the importance of competing, if necessary by gunfire, and of breaking into such reserved areas as the Spanish American trade.

The machines which were evolved to do the fighting in this competition underwent steady improvement and specialization, but no revolutionary change, between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. Once square-rigging and broadside firing had been adopted, the essential shape of vessels was determined, though individual design could still do much to give sailing superiority and the French usually built better ships than Great Britain during the eighteenth-century duel between the two countries. In the sixteenth century, under English influence, ships grew longer in proportion to their beam. The relative height of the forecastle and poop above the deck gradually came down, too, over the whole period. Bronze guns reached a high level of development even in the early seventeenth century; thereafter gunnery changed by improvement in design, accuracy and weight of shot. There were two significant eighteenth-century innovations, the short-range but large-calibre and heavy-shotted iron carronade, which greatly increased the power of even small vessels, and a firing mechanism incorporating a flintlock, which made possible more precise control of the guns.

Specialization of function and design between warships and merchant vessels was accepted by the middle of the seventeenth century, though the line was still somewhat blurred by the existence of older vessels and the practice of privateering. This was a way of obtaining naval power on the cheap. In time of war, governments authorized individual private captains or their employers to prey upon enemy shipping, taking profits from the prizes they made. It was a form of regularized piracy and English, Dutch and French privateers all operated at various times with great success against one another’s traders. The first great privateering war was that fought unsuccessfully against the English and Dutch under King William by the French.

Other seventeenth-century innovations were tactical and administrative. Signalling became formalized and the first Fighting Instructions were issued to the Royal Navy. Recruitment became more important; the press-gang appeared in England (the French used naval conscription in the maritime

provinces). In this way large fleets were manned and it became clear that, given equality of skill and the limited damage which could be done even by heavy guns, numbers were always likely to be decisive in the end.

From the seminal period of development in the seventeenth century there emerged a naval supremacy which was to last over two centuries and underpin a worldwide

pax Britannica

. Dutch competition dropped away as the Republic bent under the strain of defending its independence on land against the French. The important maritime rival of the English was France and here it is possible to see that a decisive point had been passed by the end of King William’s reign. By then, the dilemma of being great on land or sea had been decided by the French in favour of the land. From that time, the promise of a French naval supremacy was never to be revived, though French shipbuilders and captains would still win victories by their skill and courage. The English were not so distracted from oceanic power; they had only to keep their continental allies in the field, not to keep up great armies themselves. But there was a little more to it than a simple concentration of resources. British maritime strategy also evolved in a way very different from that of other sea-powers. Here, the French loss of interest in the navy of Louis XIV is relevant, for it came after the English had inflicted a resounding defeat in a fleet action in 1692, which discredited the French admirals. It was the first of many such victories which demonstrated an appreciation of the strategic reality that sea-power was in the end a matter of commanding the surface of the sea so that friendly ships could move on it in safety while those of the enemy could not. The key to this desirable end was the neutralization of the enemy’s fleet. So long as it was there, a danger existed. The early defeat of the enemy’s fleet in battle therefore became the supreme aim of British naval commanders for a century during which it gave the Royal Navy almost uninterrupted command of the seas and a formidable offensive tradition.

Naval strategy fed imperial enterprise indirectly as well as directly because it made more and more necessary the acquisition of bases from which squadrons could operate. This was particularly important in building the British empire. In the late eighteenth century, too, that empire was about to undergo the loss of much of its settled territory and this would bring further into relief the way in which European hegemony was, outside the New World, still in 1800 a matter of trading stations, island plantations and bases, and the control of carrying trade, rather than of occupation of large areas.

Less than three centuries of even this limited form of imperialism revolutionized the world economy. Before 1500, there had been hundreds of more or less self-supporting and self-contained economies, some of them

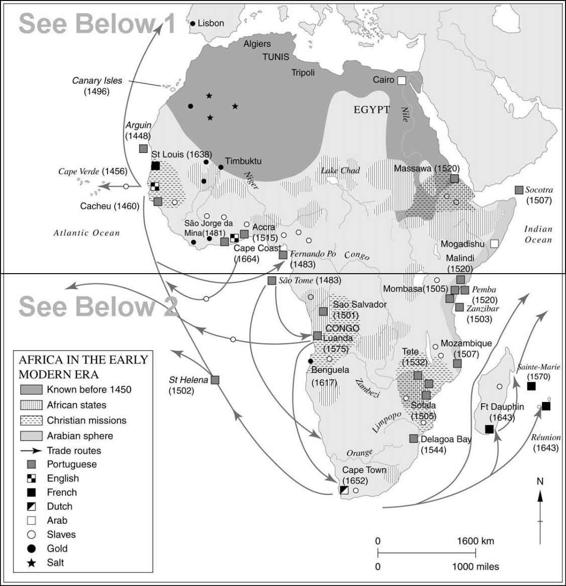

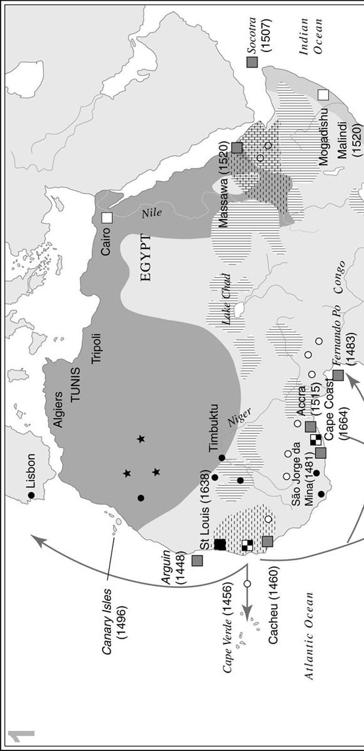

linked by trade. The Americas and Africa were almost, Australasia was entirely, unknown to Europe, communication within them was tiny in proportion to their huge extent, and there was a thin flow of luxury trade from Asia to Europe. By 1800, a worldwide network of exchange had appeared. Even Japan was a part of it and central Africa, though still mysterious and unknown, was linked to it through slavery and the Arabs. Its first two striking adumbrations had been the diversion of Asian trade with Europe to the sea routes dominated by the Portuguese and the flow of bullion from America to Europe. Without that stream, above all of silver, there could hardly have been a trade with Asia for there was almost nothing produced in Europe that Asia wanted. This may have been the main importance of the bullion from the Americas, whose flow reached its peak at the end of the sixteenth century and in the early decades of the next.

Although a new abundance of precious metals was the first and most dramatically obvious economic effect of Europe’s new interplay with Asia and America, it was less important than the general growth of trade, of which slaves from Africa for the Caribbean and Brazil formed a part. The slave-ships usually made their voyage back to Europe from the Americas loaded with the colonial produce which more and more became a necessity to Europe. In Europe, first Amsterdam and then London surpassed Antwerp as international ports, in large measure because of the huge growth of the re-export trade in colonial goods which were carried by Dutch and English ships. Around these central flows of trade there proliferated branches and sub-branches, which led to further specializations and ramifications. Shipbuilding, textiles and, later, financial services such as insurance all prospered together, sharing in the consequences of a huge expansion in sheer volume. Eastern trade in the second half of the eighteenth century made up a quarter of the whole of Dutch external commerce and during that century the number of ships sent out by the East India Company from London went up threefold. These ships, moreover, improved in design, carried more and were worked by fewer men than those of earlier times.

The material consequences of Europe’s new involvement with the world are much easier to measure than some of the others. European diet remains one of the most varied in the world and this came about in the early modern age. The coming of tobacco, coffee, tea and sugar alone brought about a revolution in taste, habit and housekeeping. The potato was to change the lives of many countries by sustaining much larger populations than its predecessors. Scores of drugs were added to the European pharmacopoeia, mainly from Asia.

Beyond such material effects it is harder to proceed. The interplay of new knowledge of the world with European mentality is especially hard to pin down. Minds were changing, as the great increase in the numbers of books about discoveries and voyages in both East and West had showed as early as the sixteenth century. Oriental studies may be said to have been founded as a science in the seventeenth century, although Europeans only began to show the impact of knowledge of the anthropologies of other people towards its close. Such developments were intensified in the unrolling of their effects by the fact that they took place in an age of printing, too, and this makes the novelty of interest in the world outside Europe hard to evaluate. By the early eighteenth century, though, there were signs of an important intellectual impact at a deep level. Idyllic descriptions of savages who lived moral lives without the help of Christianity provoked reflection; an English philosopher, John Locke, used the evidence of other continents to show that humans did not share any God-given

innate ideas. In particular, an idealized and sentimentalized picture of China furnished examples for speculation on the relativity of social institutions, while the penetration of Chinese literature (much aided by the studies of the Jesuits) revealed a chronology whose length made nonsense of traditional calculations of the date of the Flood described in the Bible as the second beginning of all men.