The New Penguin History of the World (122 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

For centuries, the preaching and rituals of the Church were virtually the only access to European culture for the Amerindian peasant, who found some of Catholicism’s features sympathetic and comprehensible. To European education, only a few had access; Mexico had no native bishop until the seventeenth century, and education, except for the priesthood, did not take a peasant much further than the catechism. The Church tended, in fact, for all the devoted work of many of its clergy, to remain an imported, colonial Church. Ironically, even the attempts of churchmen to protect the native Christians had the effect of isolating them (by, for instance, not teaching them Spanish) from the routes to integration with the possessors of power in their societies.

Perhaps this was inevitable. The Catholic monopoly in Spanish and Portuguese America was bound to mean a large measure of identification of the Church with the political structure: it was an important reinforcement for a thinly spread administrative apparatus and it was not only

crusading zeal which made the Spanish enthusiastic proselytizers. The Inquisition was soon set up in New Spain and it was the Church of the Counter-Reformation which shaped American Catholicism south of the Rio Grande. This had important consequences much later; although some priests were to play important parts in the revolutionary and independence movements of South America, and though in the eighteenth century the Jesuits were to incur the wrath of the Portuguese settlers and government of Brazil for their efforts to protect the natives, the Church as an organization never found it easy to adopt a progressive stance. In the very long run, this meant that in the politics of independent Latin America, liberalism would take on the associations of anti-clericalism it was to have in Catholic Europe. This was all in marked contrast to the religiously pluralistic society which was taking root contemporaneously in British North America.

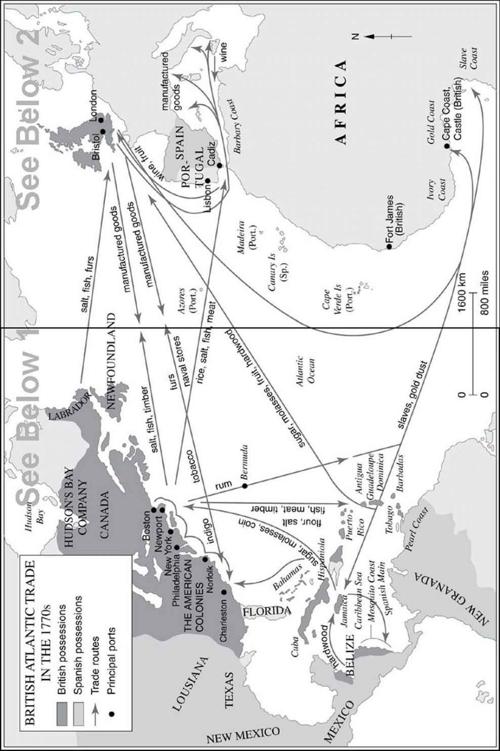

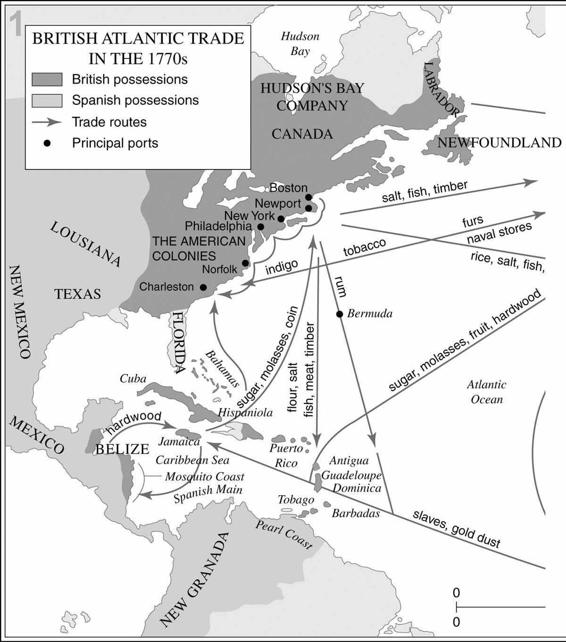

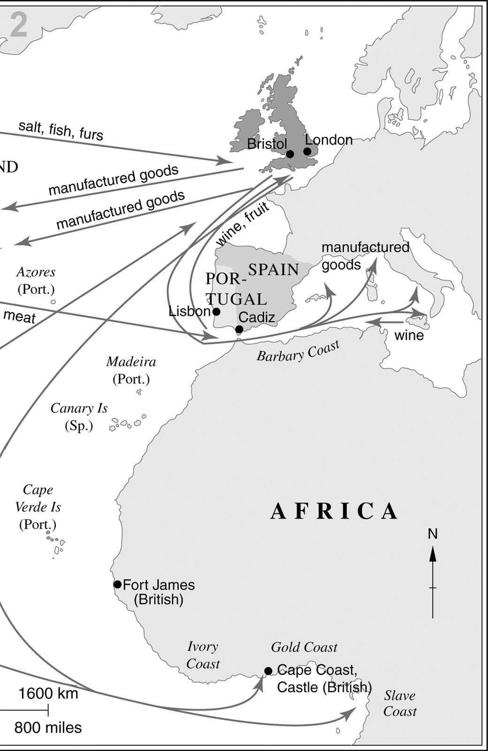

For all the spectacular inflow of bullion from the mainland colonies, it was the Caribbean islands which were of the greatest economic importance to Europe throughout most of the early modern period. This importance rested on their agricultural produce, above all on sugar, introduced first by the Arabs to Europe, in Sicily and Spain, and then carried by Europeans first to Madeira and the Canaries, and then to the New World. Both the Caribbean and Brazil were transformed economically by this crop. Medieval man had sweetened his food with honey; by 1700 sugar, though still expensive, was a European necessity. It was, with tobacco, hardwood and coffee, the main product of the islands and the tap-root of the burgeoning African slave trade. Together, these exports gave the planters great importance in the affairs of their metropolitan countries.

The story of large-scale Caribbean agriculture began with the Spanish settlers, who quickly started growing fruit (which they had brought from Europe) and raising cattle. When they introduced rice and sugar, production was for a long time held back by a shortage of labour, as the native populations of the islands succumbed to European ill-treatment and disease. The next economic phase was the establishment by later arrivals of parasitic industries: piracy and smuggling. The Spanish occupation of the larger Caribbean islands – the Greater Antilles – still left hundreds of smaller islands unoccupied, most of them on the Atlantic fringe. These attracted the attention of English, French and Dutch captains who found them useful as bases from which to prey on Spanish ships going home from New Spain, and for contraband trade with the Spanish colonists who wanted their goods. European settlements appeared, too, on the Venezuelan coast where there was salt to be had for preserving meat. Where individuals led, governmental enterprises in the form of English royal concessions and the Dutch West India Company followed in the seventeenth century.

By then, the English had for decades been looking for suitable places for what contemporaries called ‘plantations’ – that is, settler colonies – in the New World. They tried the North American mainland first. Then, in the 1620s, they established their first two successful West Indian colonies, on St Christopher in the Leeward Isles, and Barbados. Both prospered; by 1630 St Christopher had about 3000 inhabitants and Barbados about 2000. This success was based on tobacco, the drug which, with syphilis (believed to have been in Europe at Cadiz in 1493) and the cheap automobile, some have thought to be the New World’s revenge for its violation by the Old. These tobacco colonies rapidly became of great importance to England not only because of the customs revenue they supplied, but also because the new growth of population in the Caribbean stimulated demand for exports and provided fresh opportunities for interloping in the trade of the Spanish empire. Soon the English were joined by the French in this lucrative business, the French occupying the Windward Isles, the English the rest of the Leewards. In the 1640s there were about 7000 French in the West Indies, and over 50,000 English.

After this time the tide of English emigration to the New World was diverted to North America and the West Indies were not again to reach such high figures of white settlement. This was partly because sugar joined tobacco as a staple crop. Tobacco can be produced economically in small quantities; it had therefore suited the multiplication of smallholdings and the building up of a large immigrant population of whites. Sugar was economic only if cultivated in large units; it suited the big plantation, worked by large numbers, and these were likely to be black slaves, given the decline of the local population in the sixteenth century. The Dutch supplied the slaves and aspired to the sort of general commercial monopoly in the western hemisphere which they were winning in the Far East, working out of a base at the mouth of the Hudson river, New Amsterdam. This was the beginning of a great demographic change in the Caribbean. In 1643 Barbados had 37,000 white inhabitants and only 6000 black African slaves; by 1660 there were over 50,000 of the latter.

With the appearance of sugar, the French colonies of Guadeloupe and Martinique took on a new importance and they, too, wanted slaves. A complex process of growth was under way. The huge and growing Caribbean market for slaves and imported European goods was added to that already offered by a Spanish empire increasingly unable to defend its economic monopoly. This fixed the role of the West Indies in the relationships of the powers for the next century. They were long a prey to disorder, the Caribbean an area where colonial frontiers met and policing was poor and there were great prizes to be won (in one year a Dutch captain took the

great

flota

bearing home the year’s treasure from the Indies to Spain). Not surprisingly, they became the classical and, indeed, legendary hunting-ground of pirates, whose heyday was the last quarter of the seventeenth century. Gradually, the great powers fought out their disputes until they arrived at acceptable agreements, but this was to take a long time. Meanwhile, through the eighteenth century the West Indies and Brazil provided the great market for slaves and sustained most of that trade. As time passed, it too became involved in another economy besides those of Europe, Africa and New Spain: that of a new North America.

For a long time, by all the standards of classical colonial theory, settlement in North America was a poor second in attractiveness to Latin America or the Caribbean. Precious metals were not discovered there and though there were furs in the north there seemed to be little else that Europe wanted from that region. Yet there was nowhere else to go, given the Spanish monopoly to the south, and a great many nations tried it. The Spanish expansion north of the Rio Grande need not concern us, for it was hardly an occupation, more of a missionary exercise, while Spanish Florida’s importance was strategical, for it gave some protection to Spanish communications with Europe by the northern outlet from the Caribbean. It was the settlement of the Atlantic coast which drew other Europeans. There was even briefly a New Sweden, taking its place beside New Netherlands, New England and New France.

The motives for settling North America were often those which operated elsewhere, though the crusading, missionary zeal of the Reconquest mentality was almost entirely missing further north. For most of the sixteenth century the Englishmen, who were the most frequent explorers of North American possibilities, thought there might be mines there to rival those of the Spanish Indies. Others believed that population pressure made emigration desirable, and increasing knowledge revealed ample land in temperate climates with, unlike Mexico, very few native inhabitants. There was also a constant pull in the lure of finding a north-west passage to Asia.

By 1600, these impulses had produced much exploration, but only one (unsuccessful) settlement north of Florida, at Roanoke, Virginia. The English were too weak, the French too distracted, to achieve more. With the seventeenth century there came more strenuous, better-organized and better-financed efforts, the discovery of the possibility of growing some important staples on the mainland, a set of political changes in England which favoured emigration, and the emergence of England as a great naval power. Between them, these facts brought about a revolutionary transformation of the Atlantic littoral. The wilderness of 1600, inhabited by a few Indians, was a hundred years later an important site of civilization. In many places settlers had pushed as far inland as the mountain barrier of the Alleghenies. Meanwhile the French had established a line of posts along the valley of the St Lawrence and the Great Lakes. In this huge right-angle of settlement lived about a half-million white people, mainly of British and French stock.

Spain claimed all North America, but this had long been contested by the English on the ground that ‘prescription without possession availeth nothing’. The Elizabethan adventurers had explored much of the coast and gave the name ‘Virginia’, in honour of their queen, to all the territory north of thirty degrees of latitude. In 1606 James I granted a charter to a Virginia company to establish colonies. This was only formally the beginning; the company’s affairs soon required revision of its structure and there were unprofitable initiatives in plenty, but in 1607 there was already established the first English settlement in America, which was to survive, at Jamestown, in modern Virginia. It only just came through its early trials but by 1620 its ‘starving time’ was far behind it and it prospered. In 1608, the year after Jamestown’s foundation, the French explorer Samuel de Champlain built a small fort at Quebec. For the immediate future the French colony was so insecure that its food had to be brought from France, but it was the beginning of settlement in Canada. Finally, in 1609, the Dutch sent an English explorer, Henry Hudson, to find a north-east passage to Asia. When he was unsuccessful he turned completely around and sailed across the Atlantic to look for a north-western one. Instead, he discovered the river that bears his name and established a preliminary Dutch claim

by doing so. Within a few years there were Dutch settlements along the river, on Manhattan and on Long Island.

The English were in the lead and remained so. They prospered because of two new facts. One was the technique, of which they were the first and most successful exponents, of transporting whole communities, men, women and children. These set up agricultural colonies which worked the land with their own labour and soon became independent of the mother country for their livelihood. The second was the discovery of tobacco, which became a staple first for Virginia and then for Maryland, a colony whose settlement began in 1634. Further north, the availability of land which could be cultivated on European lines assured the survival of the colonies; although interest in the area had originally been awoken by the prospects of fur-trading and fishery there was soon a small surplus of grain for export. This was an attractive prospect for land-hungry Englishmen in a country widely believed in the early seventeenth century to be over-populated. Something like 20,000 went to ‘New England’ in the 1630s.