The New Penguin History of the World (121 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

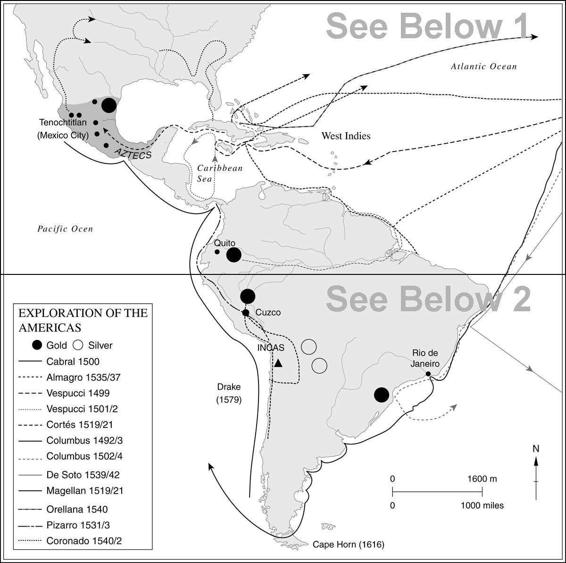

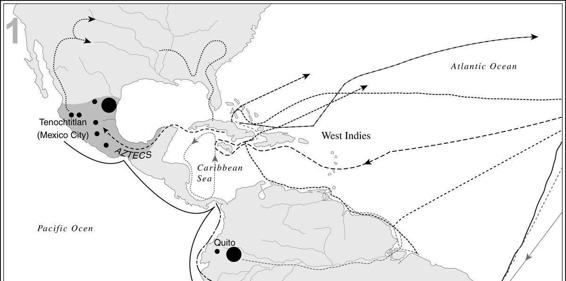

The Spanish settlers looked for land, as agriculturalists, and gold, as speculators. They had no competitors and, indeed, with the exception of Brazil, the story of the opening up of Central and South America remains Spanish until the end of the sixteenth century. The first Spaniards in the islands were often Castilian gentry, poor, tough and ambitious. When they went to the mainland they were out for booty, though they spoke as well of the message of the Cross and the greater glory of the Crown of Castile. The first penetration of the mainland had come in Venezuela in 1499. Then, in 1513, Balboa crossed the isthmus of Panama and Europeans for the first time saw the Pacific. His expedition built houses and sowed crops; the age of the

conquistadores

had begun. One among them whose adventures captured and held the imagination of posterity was Hernán Cortés. Late in 1518 he left Cuba with a few hundred followers. He was deliberately flouting the authority of its governor and subsequently justified his acts by the spoils he brought to the Crown. After landing on the coast of Vera Cruz in February 1519, he burnt his ships to ensure that his men could not go back and then began the march to the high central plateau

of Mexico, which was to provide one of the most dramatic stories of the whole history of imperialism. When they reached the city of Mexico itself, they were astounded by the civilization they found there. Besides its wealth of gold and precious stones, it was situated in a land suitable for the kind of estate cultivation familiar to Castilians at home.

Though Cortés’s followers were few, and their conquest of the Aztec empire which dominated the central plateau heroic, they had great advantages and a lot of luck. The people upon whom they advanced were technologically primitive, easily impressed by the gunpowder, steel and horses the

conquistadores

brought with them. Aztec resistance was hampered by an uneasy feeling that Cortés might be an incarnation of their god, whose return to them they one day expected. The Aztecs were very susceptible to imported diseases, too. Furthermore, they were themselves an exploiting race and a cruel one; their Indian subjects were happy to welcome the new conquerors as liberators or at least as a change of masters. Circumstances thus favoured the Spaniards. Nevertheless, in the end their own toughness, courage and ruthlessness were the decisive factors.

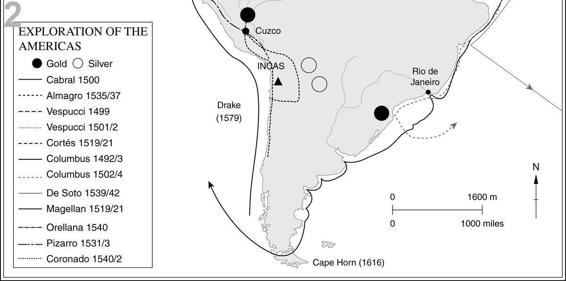

In 1531 Pizarro set out upon a similar conquest of Peru. This was an even more remarkable achievement than the conquest of Mexico and, if possible, displayed even more dreadfully the rapacity and ruthlessness of the

conquistadores

. Settlement of the new empire began in the 1540s and almost at once there was made one of the most important mineral discoveries of historical times, that of a mountain of silver at Potosi, which was to be Europe’s main source of bullion for the next three centuries.

By 1700, the Spanish empire in the Americas nominally covered a huge area from the modern New Mexico to the River Plate. By way of Panama and Acapulco it was linked by sea to the Spanish in the Philippines. Yet this huge extent on the map was misleading. The Californian, Texan and New Mexican lands north of the Rio Grande were very thinly inhabited; for the most part occupancy meant a few forts and trading posts and a larger number of missions. Nor, to the south, was what is now Chile well settled. The most important and most densely populated regions were three: New Spain (as Mexico was called), which quickly became the most developed part of Spanish America; Peru, which was important for its mines and intensively occupied; and some of the larger and long-settled Caribbean islands. Areas unsuitable for settlement by Spaniards were long neglected by the administration.

The Indies were governed by viceroys at Mexico and Lima as sister kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, dependent upon the Crown of Castile. They had a royal council of their own through which the king exercised direct authority. This imposed a high degree of centralization in theory;

in practice, geography and topography made nonsense of such a pretence. It was impossible to control New Spain or Peru closely from Spain with the communications available. The viceroys and captains-general under them enjoyed effective independence in their day-to-day business. But the colonies could be run by Madrid for fiscal advantage and, indeed, the Spaniards and Portuguese were the only powers colonizing in the western hemisphere for over a century who managed to make their American possessions not only pay for themselves but return a net profit for the metropolis. This was largely because of the flow of precious metals. After 1540 silver flooded across the Atlantic, to be dissipated, unfortunately for Spain, in the wars of Charles V and Philip II. By 1650, 16,000 tons of silver had come to Europe, to say nothing of 180 tons of gold objects.

Whether Spain got other economic benefits is harder to say. She shared with other colonizing powers of the age the belief that there was only a limited amount of trade to go around; it followed that trade with her colonies should be reserved to her by regulation and force of arms. Furthermore, she endorsed another commonplace of early colonial economic theory, the view that colonies should not be allowed to develop industries which might reduce the opportunities available to the home country in their markets. Unfortunately, Spain was less successful than other countries in drawing advantage from this. Though they prevented the development of industry, apart from the processing of agricultural crops, mining and handicrafts in America, the Spanish authorities were increasingly unable to keep out foreign traders (interlopers as they came to be called) from their territories. Spanish planters soon wanted what metropolitan Spain could not supply – slaves, especially. Apart from mining, the economy of the islands and New Spain rested on agriculture. The islands soon came to depend on slavery; in the mainland colonies, a Spanish government unwilling to countenance the enslavement of the conquered populations evolved other devices to assure the supply of labour. The first, started in the islands and extended to Mexico, was a kind of feudal lordship: a Spaniard would be given an

encomienda

, a group of villages over which he extended protection in return for a share of their labour. The general effect was not always easily distinguishable from serfdom, or even from slavery, which soon came to mean black African slavery.

The presence from the start of large pre-colonial native populations to provide labour did as much as the nature of the occupying power to differentiate the colonialism of Central and South America from that of the north. Centuries of Moorish occupation had accustomed the Spanish and Portuguese to the idea of living in a multiracial society. There soon emerged in Latin America a population of mixed blood. In Brazil, which

the Portuguese finally secured from the Dutch after thirty years’ fighting, there was much interbreeding, both with the indigenous peoples and with the growing black population of slaves, who had first been imported to work on the sugar plantations in the sixteenth century. In Africa, too, the Portuguese showed no concern at racial interbreeding, and its lack of a colour bar has been alleged to have been a palliative feature of Portuguese imperialism.

None the less, though the establishment of racially mixed societies over huge areas was one of the enduring legacies of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, these societies were stratified along racial lines. The dominant classes were always the Iberian-born and the

creoles

, persons of European blood born in the colonies. As time passed, the latter came to feel that the former, called

peninsulares

, excluded them from key posts and were antagonistic towards them. From the

creoles

there led downwards a blurred incline of increasing gradations of blood to the poorest and most oppressed, the pure Indians and black slaves. Though Indian languages survived, often thanks to the efforts of the Spanish missionaries, the dominant languages of the continent became, of course, those of the conquerors. This was the greatest single formative influence making for the cultural unification of the continent, though another of comparable importance was Roman Catholicism. The Church played an enormous part in the opening of Spanish (and Portuguese) America. The lead was taken from the earliest years by the missionaries of the regular orders – Franciscans, in particular – but for three centuries their successors worked away at the civilization of native Americans. They took Indians from their tribes and villages, taught them Christianity and Latin (the early friars often kept them from learning Spanish, to protect them from corruption by the settlers), put them in trousers and sent them back to spread the light among their compatriots. The mission stations of the frontier determined the shapes of countries which would only come into existence centuries later. They met little resistance. Mexicans, for example, enthusiastically adopted the cult of the Blessed Virgin, assimilating her with the native goddess, Tonantzui.

For good and ill the Church saw itself from the start as the protector of the Indian subjects of the Crown of Castile. The eventual effect of this would only be felt after centuries had brought important changes in the demographic centre of gravity within the Roman communion, but it had many implications visible much earlier than this. It was in 1511 that the first sermon against the way the Spanish treated their new subjects was preached (by a Dominican) at Santo Domingo. From the start, the monarchy proclaimed its moral and Christian mission in the New World. Laws were passed to protect the Indians and the advice of churchmen was sought

about their rights and what could be done to secure them. In 1550 an extraordinary event took place when the royal government held a theological and philosophical enquiry by debate into the principles on which the New World peoples were to be governed. But America was far away, and enforcement of laws difficult. It was all the harder to protect the native population when a catastrophic drop in its numbers created a labour shortage. The early settlers had brought smallpox to the Caribbean (its original source seems to have been Africa) and one of Cortés’s men took it to the mainland; this was probably the main cause of the demographic disaster of the first century of Spanish empire in America.

The Church, meanwhile, was almost continuously at work to convert the natives (two Franciscans baptized 15,000 Indians in a single day at Xocomilcho) and then to throw around them the protection of the mission and the parish. Others did not cease to make representations to the Crown. The name of one, Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Dominican, cannot be ignored. He had come out as a settler, only to become the first priest ordained in the Americas and thereafter, as theologian and bishop, he spent his life trying to influence Charles V’s government, and not without success. He brought to bear the discipline of refusing absolution even in the last rites to those whose confessions left him unsatisfied over their treatment of Indians, and argued against opponents on a thoroughly medieval basis. He assumed, with Aristotle, that some men indeed were ‘by nature’ slaves (he had black slaves of his own) but denied that the Indians were among them. He was to pass into historical memory, anachronistically, as one of the first critics of colonialism, largely because of the use made of his writings two hundred years later by a publicist of the Enlightenment.