The New Penguin History of the World (187 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

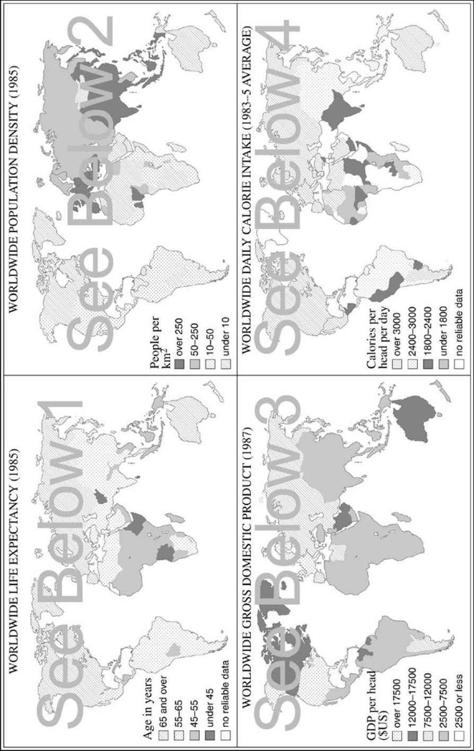

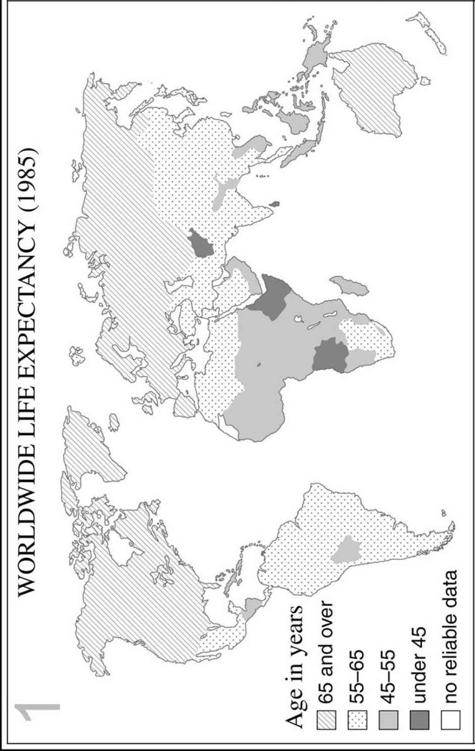

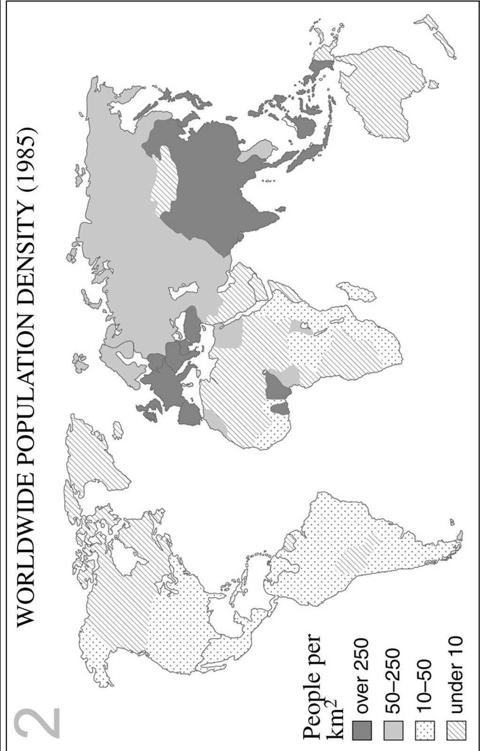

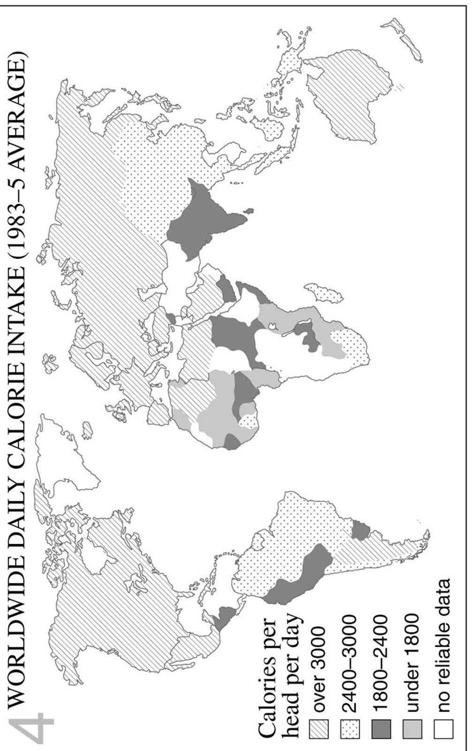

For all that, paradoxically, there may well be more subsistence farmers in the world today than in 1900, just because there are more people. Their share of cultivated land and of the value of the crops produced, though, has fallen. The 2 per cent of the farmers who live in developed countries now supply about half the world’s food. In Europe the peasant is fast disappearing, as he disappeared in Great Britain two hundred years ago. But this change has been unevenly spread and easily disrupted. Russia was traditionally one of the great agricultural economies, but as recently as 1947 suffered famine so severe as to provoke outbreaks of cannibalism once more. Local dearth is still a danger in countries with large and rapidly growing populations where subsistence agriculture is the norm and productivity remains low. Just before the First World War, the British yield of wheat per acre was already more than two and a half times that of India; by 1968 it was roughly five times. Over the same period the Americans raised their rice yield from 4.25 to nearly 12 tons an acre, while that of Burma, once the ‘rice bowl of Asia’, rose only from 3.8 to 4.2. In 1968, one agricultural worker in Egypt was providing food for slightly more than one family, while in New Zealand each farm employee was producing enough for forty.

Countries economically advanced in other ways show the greatest agricultural productivity. Countries in greatest need have found it impossible to produce crops more cheaply than can leading industrial economies. Ironic paradoxes result: the Russians, Indians and Chinese, big grain and rice producers, have found themselves buying American and Canadian

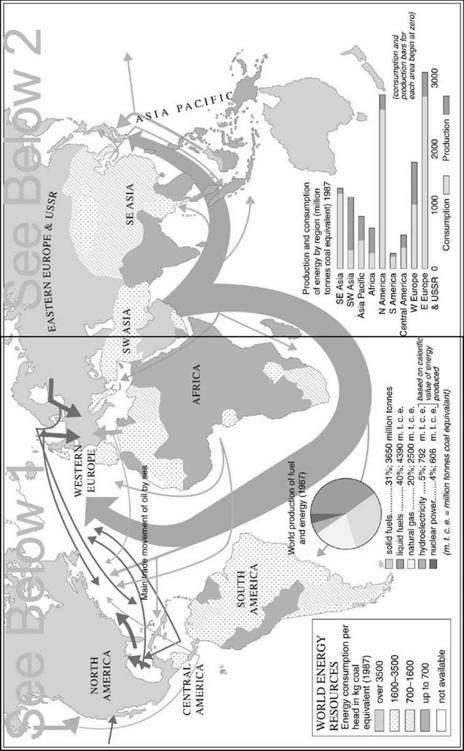

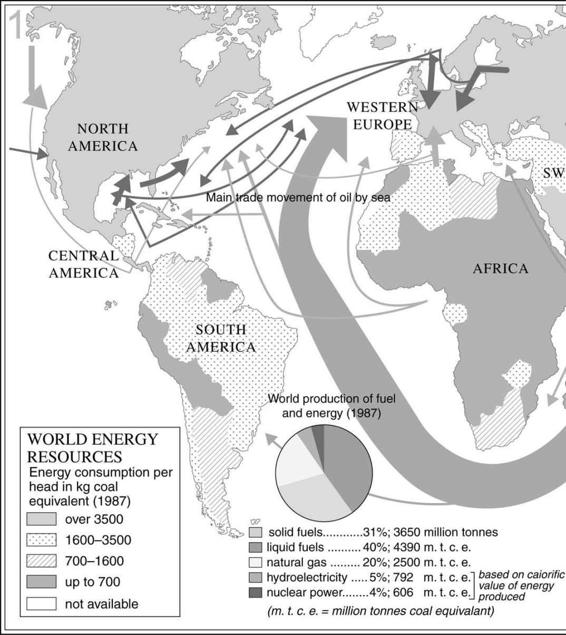

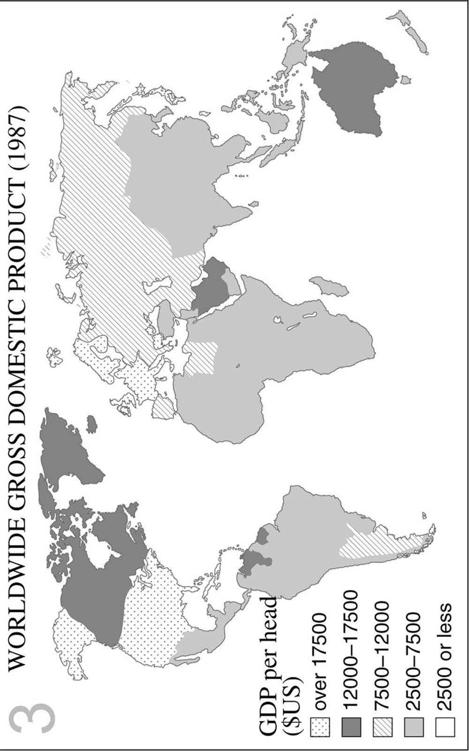

wheat. Disparities between developed and undeveloped countries have widened in the decades of plenty. Roughly half of mankind now consumes about six-sevenths of the world’s production; the other half shares the rest. The United States has been the most extravagant consumer by far. In 1970 the half-dozen or so Americans in every 100 human beings used about 40 of every 100 barrels of oil produced in the world each year. They each consumed annually roughly a quarter-ton of paper products; the corresponding figure for China was then about twenty pounds. The electrical energy used by China for all purposes in a year at that time would (it was said) just have sustained the supply of power to the United States’ air conditioners. Electricity production, indeed, is one of the best ways of making comparisons, since relatively little electrical power is traded internationally and most of it is consumed in the country where it is generated. At the end of the 1980s, the United States produced nearly 40 times as much electricity per capita as India, 23 times as much as China, but only 1.3 times as much as Switzerland.

In all parts of the world the disparity between rich and poor nations has grown more and more marked since 1945, not usually because the poor have grown poorer, but because the rich have grown much richer. Almost the only exceptions to this were to be found in the comparatively rich (by poor world standards) economies of the USSR and Eastern Europe, where mismanagement and the exigencies of a command economy imposed lower growth rates, or even no growth at all. With these exceptions, even spectacular accelerations of production (some Asian countries, for example, pushed up their agricultural output between 1952 and 1970 proportionately more than Europe and much more than North America) have rarely succeeded in improving the position of poor countries in relation to that of the rich, because of their rising populations – and rich countries, in any case, began at a higher level.

Although their rankings in relation to one another may have changed, those countries that enjoyed the highest standards of living in 1950 still, by and large, enjoy them today (and have been joined by Japan). These are the major industrial countries. Their economies are today the richest per capita, and their example spurs poorer countries to seek their own salvation in economic growth, which is too often read as industrialization. True, major industrial economies today do not much resemble their nineteenth-century predecessors. The old heavy and manufacturing industries, which long provided the backbone of economic strength, are no longer simple and satisfactory measures of it. Once-staple industries in leading countries have declined. Of the three major steel-making countries of 1900, the first two (the USA and West Germany) were still among the

first five world producers eighty years later, but in third and fifth places respectively; the United Kingdom (third in 1900) came tenth in the same world table – with Spain, Romania and Brazil close on her heels. Nowadays, Poland makes more steel than did the USA a century ago. What is more, newer industries often found a better environment for rapid growth in some developing countries than in the mature economies. Thus the people of Taiwan came by 1988 to enjoy per capita GDP nearly eighteen times that of India, while that of South Korea, too, was fifteen times as big.

Twentieth-century economic growth has often been in sectors – electronics and plastics are examples – which barely existed even in 1945 and in new sources of power. Coal replaced running water and wood in the nineteenth century as the major source of industrial energy, but long before 1939 it was joined by hydro-electricity, oil and natural gas; very recently, power generated by nuclear fission was added to these. Industrial growth has raised standards of living as power costs have come down and with them those of transport. One particular innovation was of huge importance. In 1885 the first vehicle propelled by internal combustion was made – one, that is to say, in which the energy produced by heat was used directly to drive a piston inside the cylinder of an engine, instead of being transmitted to it via steam made in a boiler with an external flame. Nine years later came a four-wheeled contraption made by the French Panhard Company, which is a recognizable ancestor of the modern car. France, with Germany, dominated the production of cars for the next decade or so and they remained rich men’s toys. This is automobile pre-history. Automobile history began in 1907, when Henry Ford, an American, set up a production line for what became famous as his ‘Model T’. Planned deliberately for a mass market, its price was low. By 1915 a million Ford cars were being made each year and by 1926 the Model T cost less than $300 (about £60 in British money at rates then current). An enormous commercial success was underway.

So was a social and economic revolution. Ford changed the world. By giving the masses something previously considered a luxury, and a mobility unavailable even to the millionaire fifty years earlier, his impact was as great as the coming of railways. This increase in amenity was to spread around the world, too, with enormous consequences. A worldwide car manufacturing industry was one result, often dominating domestic manufacturing sectors and bringing, eventually, large-scale international integration; in the 1980s eight large producers made three out of four of the world’s cars. The industry stimulated huge investment in other sectors, too; only a few years ago, half the robots employed in the world’s industry were welders in car factories, and another quarter painted their products. Over a similarly long term, car production enormously stimulated demand for oil. Huge numbers of people came to be employed in supplying fuel and other services to car owners. Investment in road-building became a major concern of governments, as it had not been since the days of the Roman Empire.