The New Penguin History of the World (123 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Another distinctive feature of the New England colonies was their association with religious dissent and Calvinistic Protestantism. They would not have been what they were without the Reformation. Although the usual economic motives were at work in the settlements, the leadership among immigrants to Massachusetts in the 1630s of men associated with the Puritan wing of English Protestantism bore fruit in a group of colonies, whose constitutions varied from theocratic oligarchy to democracy. Though sometimes led by members of the English gentry, they shed more rapidly than the southern colonies their inhibitions about radical departures from English social and political practice, and their religious nonconformity did as much as the conditions in which they had to survive to bring this about. At some moments during the English constitutional troubles of the mid-century it even seemed that the colonies of New England might escape from the control of the Crown altogether, but this did not happen.

After the Dutch settlements of what was subsequently New York State had been swallowed up by the English, the North American littoral in 1700 from Florida north to the Kennebec river was organized as twelve colonies (a thirteenth, Georgia, appeared in 1732) in which lived some 400,000 whites and perhaps a tenth as many black slaves. Further north lay still disputed territory and then lands that were indisputably French. In these, colonists were much thinner on the ground than in the English settlements. There were perhaps 15,000 French in North America in all and they had benefited from no such large migrations of communities as had the English colonies. Many of them were hunters and trappers, missionaries and explorers, strung out over the length of the St Lawrence

and dotted about in the Great Lakes region and even beyond. New France was a huge area on the map, but outside the St Lawrence valley and Quebec it was only a scatter of strategically and commercially important forts and trading posts. Nor was density of settlement the only difference between the French and English colonial zones. New France was closely supervised from home; after 1663 a company structure had been abandoned in favour of direct royal rule and Canada was governed by a French governor with the advice of the

intendant

much as a French province was governed at home. There was no religious liberty; the Church in Canada was monopolistic and missionary. Its history is full of glorious examples of bravery and martyrdom, and also of bitter intransigence. The farms of the settled area were grouped in

seigneuries

, a device which had some value in decentralizing administrative responsibility. Social forms therefore reproduced those of the Old World much more than those in the English settlements, even to the extent of throwing up a nobility with Canadian titles.

The English colonies were very diverse. Strung out as they were over almost the whole Atlantic seaboard, they contained a great variety of climate, economy and terrain. Their origins reflected a wide range of motives and methods of foundation. They soon became somewhat ethnically mixed, for after 1688 Scottish, Irish, German, Huguenot and Swiss emigrants had begun to arrive in appreciable numbers, though for a very long time the predominance of the English language and the relatively small numbers of non-English-speaking immigrants would maintain a culture overwhelmingly Anglo-Saxon. There was religious diversity and even by 1700 a large measure of effective religious toleration, though some of the colonies had close association with specific religious denominations. All this increased the colonies’ difficulty in seeing themselves as one society. They had no American centre; the Crown and the home country were the foci of the colonies’ collective life, as English culture was still their background. None the less, it was already obvious that the English North American colonies offered individuals opportunities for advancement unavailable either in the more strictly and closely regulated society of Canada or at home in Europe.

By 1700, some colonies had already shown a tendency to grasp whatever freedom from royal control was available to them. It is tempting to look back a long way for evidence of the spirit of independence which was later to play so big a part in popular tradition. In fact, it would be a misconception to read the prehistory of the United States in these terms. The ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ who landed at Cape Cod in 1620 were not rediscovered or inserted in their prominent place in the national mythology until the end of the eighteenth century. Yet they had, indeed, wanted to make a

New

England. What can be seen much earlier than the idea of independence is the emergence

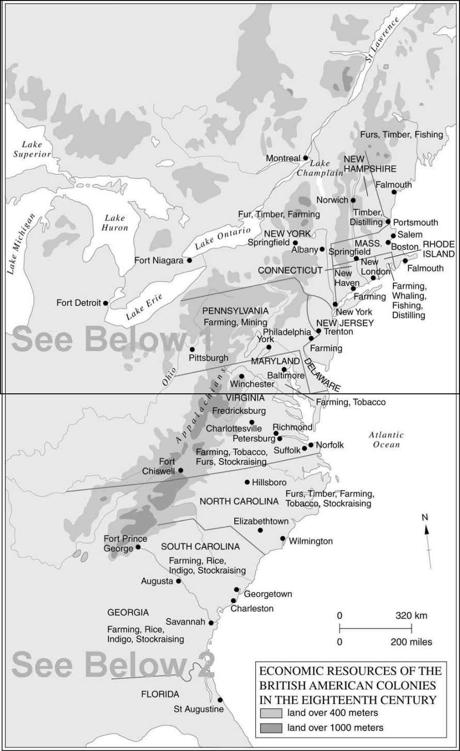

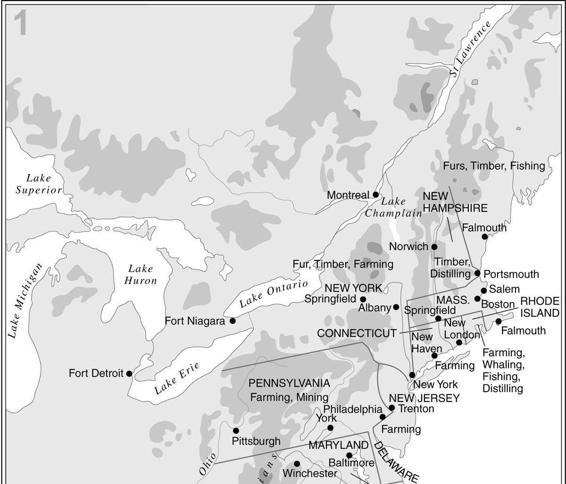

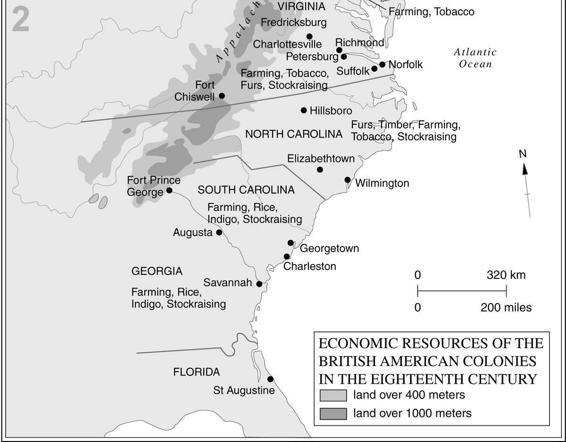

of facts which would in the future make it easier to think in terms of independence and unity. One was the slow strengthening of a representative tradition in the first century of settlement. For all their initial diversity, in the early eighteenth century each colony settled down to work through some sort of representative assembly which spoke for its inhabitants to a royal governor appointed in London. Some of the settlements had needed to cooperate with one another against the Indians at an early date, and in the French wars this had become even more important. When the French loosed their Huron allies against the British colonists, it helped to create a sense of common interest among the individual colonies (as well as spurring on the British to enlist on their side the Iroquois, the hereditary foes of the Huron). From economic diversity, too, a measure of economic interrelatedness was emerging. The middle and southern colonies produced plantation crops of rice, tobacco, indigo and timber; New England built ships, refined and distilled molasses and grain spirits, grew corn and fished. There was a growing feeling, and an apparent logic in thinking, that the Americans might perhaps be able to run their affairs in their own interest – including that of the West Indian colonies – better than in that of the mother country. Economic growth was changing attitudes, too. The northern mainland colonies of New England were on the whole underprized and even disliked in the mother country. They competed in shipbuilding and, illegally, in the Caribbean trade; unlike plantation colonies, they produced nothing that the mother country wanted. Besides, they were full of religious dissenters.

In the eighteenth century British America made great progress in wealth and civilization. The total colonial population had continued to grow and was well over a million by halfway through the century. It was being pointed out in the 1760s that the mainland colonies were going to be worth much more to Great Britain than the West Indies had been. By 1763, Philadelphia could rival many European cities in stylishness and cultivation. A great uncertainty had been removed in 1763, too, for Canada had been conquered and was by the peace treaty of that year to remain British. This changed the outlook of many Americans both towards the value of the protection afforded by the imperial government and towards the question of further expansion to the west. As farming settlers tended to fill up the coastal plain they came to press through the mountain barrier and down the river valleys beyond, eventually to the upper Ohio and the north-west. The danger of conflict with the French as a result was now removed, but this was not the only consideration which faced the British government in handling this movement after 1763. There were the rights and the likely reactions of the Indians to take into account. To antagonize them would be to court danger, but if Indian wars were to be avoided by holding the colonists back, then the frontier would have to be policed by British troops for that purpose, too. The result was a decision of government in London to impose a western land policy which would limit expansion, to raise taxes in the colonies to pay for the costs of the defending forces, and to tighten up the commercial system and cease to wink at infringements in its working. It was unfortunate that all this was coming to a head in the last years in which the old assumptions about the economics of colonial dependencies and their relationship to the mother country were accepted without demur by the makers of colonial policy.

By then about two and a half centuries had gone by since European settlements in the New World began. The overall effect of expansion in the Americas upon European history had already been immense, but is far from easy to define. Eventually, it is clear, all the colonial powers had, by the eighteenth century, been able to extract some economic profit from their colonies, though they did so in different ways. The flow of silver to Spain was the most obvious, and this had, of course, implications for the European economy as a whole and even for Asia. Growing colonial populations also helped to stimulate European exports and manufactures. In this respect the English colonies were of the greatest importance, pointing the way to a growing flow of people from Europe, which was to culminate in the last of that continent’s major folk-migrations in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To colonial expansion, too, must be linked the enormous growth of European shipping and shipbuilding. Whether engaged in slaving, contraband trading, legal import and export between metropolis and colony or fishing to supply new consumer markets, shipbuilders, shipowners and captains benefited. There was an incremental and incalculable effect at work. It is thus very hard to sum up the total effect of the possession of American colonies on the imperialist powers in the first age of imperialism.

Of the overriding cultural and political importance of that fact in the long run we can speak with more confidence: the western hemisphere was to be culturally European. Spanish, Portuguese and English might be very different, but they offered edited versions of the same text. They all brought selections from European civilization with them. Politically, that was to mean that from Tierra del Fuego to Hudson Bay two continents would eventually be organized on European legal and administrative principles even when they ceased to remain dependent on colonial power. The hemisphere was also going to be Christian; when Hinduism or Islam eventually made their appearance there, it would be as the possession of small minorities, not as rivals to a basically Christian culture.

More specifically within these generalities, great political importance was to lie in the further differentiation of the Americas, north and south. It had been true that in cultural terms North American native life could offer no such impressive human achievements as the civilizations of Central and South America. But colonialism was a differentiating fact, too. It is not fanciful to recall ancient parallels. The colonies of the ancient Greek cities were set up by their parent states as communities largely independent, in a way similar to the English settlements of the North American littoral. Once established, they tended to evolve towards a self-conscious identity of their own. The Spanish empire displayed the deployment of a regular pattern of institutions essentially metropolitan and imperial, rather as had done the provinces of imperial Rome. It took time for it to be clear that the basic forms already given to the evolution of British North America were to shape the kernel of a future world power. That evolution was therefore to prove a shaper of world as well as American history. Two great transforming factors had still to operate before the North American future was fixed in its main lines: the differing environments revealed as the northern continent filled up by movement to the west, and a much greater flow of non-Anglo-Saxon immigration. But these forces would flow into and around moulds set by the English inheritance, which would leave its mark on the future United States as Byzantium left its own on Russia. Nations do not shake off their origins, they only learn to view them in different ways. Sometimes outsiders can see this best. It was a German statesman who remarked towards the end of the nineteenth century that its most important international fact was that Great Britain and the United States spoke the same language.