The Modern Middle East (75 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

SOURCE:

World Bank, Development Indicators Database, “Passenger Cars (per 1,000 People),”

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.VEH.PCAR.P3

.

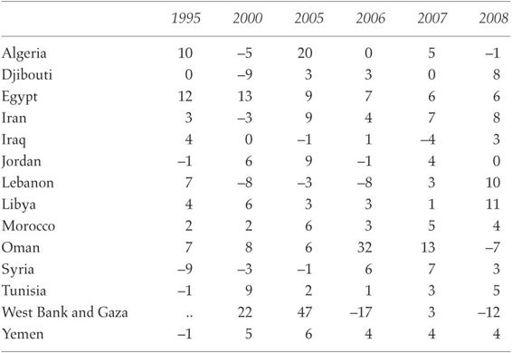

Table 18.

Annual Growth Rate of CO

2

Emissions in the Middle East

SOURCE:

World Bank, Environment Data and Statistics, “CO2 Emissions Annual Growth Rate,”

http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/EASTASIAPACIFICEXT/EXTEAPREGTOPENVIRONMENT/0,,menuPK:502908pagePK:51065911piPK:64171011theSitePK:502886,00.html

.

Information on environmental degradation in the Middle East is not readily available. However, some statistics from Iran can help put things into perspective. Although the average life span of a car is estimated at 15.9 years, international sanctions and official restrictions on car imports have pushed the age of most cars in Iran to between 10 and 22 years. Every twenty-four hours, cars operating in Tehran alone produce sixteen tons of tire particles, seven tons of asbestos (used in their brake shoes), and five tons of lead. Every year, 495,000 tons of pollutants are produced in Tehran alone, accounting for 25 percent of all the pollutants produced in the country. The city’s population, meanwhile, is estimated at around twelve million inhabitants. Tehran officials estimate that air pollution kills on average forty-six hundred residents every year. Countless others suffer from poor vision, burning eyes, and respiratory problems because of the city’s heavy, soupy air.

19

In the mid-and late 2000s, several times the Iranian government ordered the closure of schools and government offices in Tehran and encouraged Tehranis to stay indoors in order to avoid the city’s polluted air. Meanwhile, demand for even more cars far surpasses the available supply.

These and other similar statistics have made it difficult for officials in Iran and elsewhere to continue ignoring the adverse effects of environmental pollution. As pollution rates approach crisis levels, government agencies and to a lesser extent nongovernmental organizations have become active in trying to reverse some of these alarming trends. Every government in the region has set up a cabinet-level agency or a separate ministry devoted to the environment.

20

In several countries popular awareness of the importance of environmental protection has increased. In Iran, for example, a Green Party started low-key operations in the mid-2000s and is trying to attract members. A study conducted in Sharjah in the UAE found that there has been a steady rise in environmental awareness among women in the emirate.

21

Official measures and popular attitudes regarding environmental protection still have a long way to go, however. The demands for industrial and economic development are far too great to allow policy makers to devote financial and technological resources to environmental protection. Official rhetoric notwithstanding, the rates at which the air gets polluted, landfills are capped with refuse, and industrial and domestic waste is generated dwarf the limited resources that governments allocate to environmental initiatives or the small steps that people take on their own. In many of the more populous and less wealthy countries—Iran, Iraq, Egypt, and Morocco chief among them—environmental pollution has already reached crisis levels, yet many of the developments that lead to environmental degradation

continue full speed ahead. Environmental pollution in the Middle East is not simply a challenge of the future; it is a crisis of the present. Neglect or insufficient attention will only deepen the crisis.

Equally troublesome is the increasing scarcity of water in the region. Most parts of the Middle East are among the most arid in the world, and in many Middle Eastern countries rainfall levels tend to be irregular, localized, and unpredictable. Of all the countries of the region, only Iran, Turkey, and Lebanon have adequate rainfall and other water resources to meet their present and future needs, including those of agriculture. More than half the countries of the Middle East, however, are currently facing serious water shortages.

22

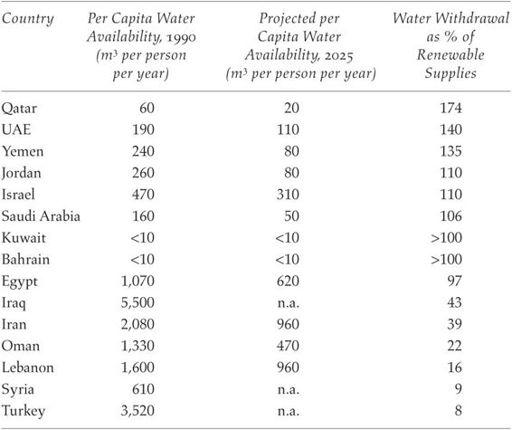

Per capita water supplies are projected to decline throughout the region over the next two decades or so, and, as table 19 demonstrates, many Middle Eastern countries are already withdrawing a greater percentage of water from renewable supplies than is being replenished. The costs of water supply and sanitation are estimated to be higher in the Middle East than in any other part of the world, being twice over those in North America and five times those in Southeast Asia. It is estimated that by 2025 Middle Eastern countries will need four times as much water as they now have available in their indigenous natural resources.

23

By 2050, per capita annual water availability throughout the Middle East and North Africa will decline from today’s one thousand cubic meters to five hundred.

24

Regarding the role and importance of water in the future of the Middle East, two factors must be kept in mind. First, extremely high rates of population growth and inefficient water usage practices have aggravated and will continue to aggravate the scarcity of water supplies caused by the Middle East’s climate. Some of the main causes and consequences of rapid population growth in the Middle East were discussed in the last section. Further exacerbating the problems of water scarcity (as well as poor water quality) is the inadequate management of what little is available. Inefficient use of water for irrigation and industrial purposes is widespread throughout the Middle East. As one observer has noted, “Great quantities of water are lost through inefficient irrigation systems such as flood irrigation of fields, unlined or uncovered canals, and evaporation from reservoirs behind dams. Pollution from agriculture, including fertilizer and pesticide runoffs as well as increased salts, added to increasing amounts of industrial and toxic waste and urban pollutants, combine to lower the quality of water for countries downstream . . . increasing their costs, and provoke dissatisfaction and

frustration, . . . creating irritations that can lead to conflicts.”

25

In the states of the Gulf Cooperation Council, ambitious development plans, often made possible by extraordinary state wealth, seldom take into account the region’s aridity and often feature the creation of tropical landscapes that are extremely harmful to the natural environment and especially to existing water resources.

Table 19.

Per Capita Water Availability and the Ratio of Supply and Demand in the Middle East

SOURCE:

Mostafa Dolatyar and Tim Gray,

Water Politics in the Middle East:A Context for Conflict or Cooperation

? (New York: Macmillan, 2000), p. 81.

A second factor to consider is that except for the three countries of Lebanon, Turkey, and Iran, the countries of the Middle East are dependent on exogenous sources of water. Apart from rainfall, whose levels are almost uniformly low throughout the region, there are two other major sources of freshwater in the Middle East, namely rivers and aquifers (underground water formations). Both of these sources, especially rivers, at times traverse international boundaries, with one country having the ability to significantly influence the flow of water into neighboring countries.

The significance of water is particularly magnified in Israel and the Occupied Territories, where close geographic locations and contending claims to the same pieces of land have given a special urgency to scarcity of water resources. This importance is far greater than there is room here to discuss. Briefly, however, a couple of points merit mentioning. Within the Occupied Territories, the average aggregate per capita water consumption for Jewish settlements ranges between 90 and 120 cubic meters, whereas for Palestinians it is 25 to 35 cubic meters. Israeli authorities do not allow Palestinians to dig new wells. Israeli settlers and military authorities, however, are allowed to dig new wells, which Palestinians claim are often deeper than existing ones and thus dry up Palestinian wells. Also, Israelis in general and Israeli settlers in particular pay a much lower price for water than do Palestinians in the Occupied Territories.

26

Altogether, some 40 to 50 percent of Israel’s water is estimated to come from aquifers in the West Bank and Gaza, thus adding to the practical needs of the Jewish state to hold on to biblical “Judea and Samaria.”

27

Another 20 percent of Israel’s water supply is estimated to come from the Golan Heights. Combined, Israel receives some two-thirds of its water from the areas it occupied in 1967.

28

The potential for international hostilities and cross-border conflicts over water is greatest, however, along the region’s three major river basins, the Tigris-Euphrates, the Nile, and the Jordan. The Tigris and Euphrates Rivers originate in Turkey and flow down to Syria (only a small portion of the Tigris goes through Syria) and then Iraq, forming the Shatt al-Arab in the south and then pouring into the Persian Gulf. Up until the 1960s, all three countries shared the water resources without tension. However, in the 1960s and especially the 1970s, Syria and Turkey began exploiting water from the Euphrates in significant amounts, resulting in the initiation of a series of trilateral agreements among the countries. The easing of tensions did not last long, however, as in the mid-1980s Turkey announced the initiation of an ambitious plan to build twenty-two dams on the Euphrates under a scheme called the Southeast Anatolian Development Project (Turkish acronym GAP). If and when the GAP is completed, it is estimated to reduce the river’s flow to Syria by some 30 to 50 percent over the next fifty years.

29

As for the Nile basin, the stakes are especially high for Egypt, which is completely dependent on the Nile and whose population continues to grow at alarming rates. Over 95 percent of Egypt’s agricultural production is from irrigated land, but about 85 percent of the flow of the Nile into Egypt originates in the Ethiopian plateau.

30

Ten different countries share the Nile or one of its two main tributaries—the Blue Nile and the White Nile—and

chronic political instability in these countries, especially in Ethiopia and Sudan, is of particular concern to Egypt. Despite long-standing plans, Ethiopia has not been able to attract sufficient international investments and technical knowledge to fully exploit the Blue Nile’s potential, a failure about which Egypt has been quite happy so far. However, if and when Ethiopia’s development plans allow for its exploitation of the Blue Nile, the water situation for Egypt and the other countries concerned could greatly change for the worse.

31

Because of its strategic location and the long history of open hostilities among the countries that share its water, the Jordan River has received the most attention as a source of future conflict over water in the Middle East, even though it is actually more of a rivulet than a river in the proper sense of the word. In fact, the average intact flow of the Jordan River is less than 2 percent of the Nile, 5 percent of the Euphrates, and slightly more than 3 percent of the Tigris.

32

The river is also subject to great seasonal fluctuations, carrying as much as 40 percent of its total annual flow in winter months and as little as 3 to 4 percent in the summer.

33

From 1987 to 1991, the area surrounding the river experienced a severe drought that further reduced its annual discharge. Added to this were the adverse consequences of a series of development projects Syria started in the late 1980s in the upper Yarmuk River, a major tributary of the Jordan River, which in turn increased salinity in the Jordan and lowered water levels in the Dead Sea.

34