The Modern Middle East (74 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

SOURCE:

World Bank,

World Development Indicators

2009 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012), pp. 112–14; World Bank, Development Indicators Database, “Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman),”

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN

.

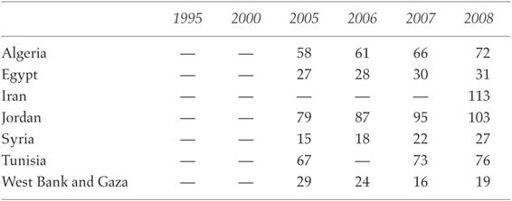

A second reason for the high rate of population growth in the Middle East is the migration of many “guest workers” to the oil-rich countries of the Arabian peninsula in search of employment. The oil boom created vast employment opportunities in the oil monarchies, which had insufficient labor resources. As a result, beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, expatriate workers began streaming into the oil monarchies in search of jobs and better opportunities. By 2008, foreigners composed more than 77 percent of the total labor force in the oil-rich countries of the Arabian peninsula (table 15). Most of the earlier immigrants came from the less wealthy parts of the Arab world, such as Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, the Palestinian territories, and Yemen. Significant numbers also come from the Philippines and South Asia, especially India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Pakistan. Although they could not enjoy many of the economic privileges that citizens enjoyed, many expatriates decided to stay and have now become part of the population. In fact, as much as 85 percent of the populations of Qatar and the United Arab Emirates are made up of noncitizens. After the Gulf War, Kuwait and some of the other Gulf states compelled many Palestinians and other Arab expatriates to leave—in retaliation for the PLO’s siding with Iraq during the conflict—and in recent years there has been an attempt to encourage the immigration of workers from the Indian subcontinent and the Philippines instead of other Arab countries. Nevertheless, the overall structure of the population remains largely intact, as does overdependence on foreign laborers.

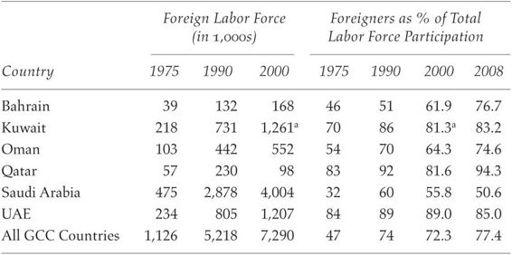

The consequences of rapid population growth rates, whether due to natural increases or immigration, are manifold. To begin with, the population of the Middle East tends to be skewed in favor of the young, especially those under the age of fourteen, who constitute some 31 percent of the total population (table 16). Such a young population poses particular challenges, especially in such areas as adequate schooling (at both high school and university levels), the provision of health care and other necessary facilities, and future employment opportunities. As we saw in chapter 10, Middle Eastern states are ill equipped to create adequate employment opportunities for existing and new entrants into the job market in the coming decades. There are other, more immediate ramifications as well. Adequate and

affordable housing is a major concern; its insufficient availability has resulted in the growth of vast shantytowns on the margins of all Middle Eastern cities.

11

Overpopulation and housing shortages are endemic throughout the Middle East. Those who can afford to live outside squatter settlements often either build unsafe dwellings without official permits or stay with family and friends. In Fez, Morocco, for example, one-family houses sometimes have thirty families living within them, with as many as three families occupying a single room.

12

Table 15.

Foreign Labor Force in the Oil Monarchies, 1975–2008

SOURCE:

Nasra M. Shah, “Restrictive Labour Immigration Policies in the Oil-Rich Gulf: Effectiveness and Implications for Sending Asian Countries,” paper presented at the United Nations Expert Group Meeting on International Migration and Development in the Arab Region, Beirut, May 15–17, 2006,

www.un.org/esa/population/meetings/EGM_Ittmig_Arab/P03_Shah.pdf

, p. 17; Michael Bonine, “Population, Poverty, and Politics: Contemporary Middle East Cities in Crisis,”

in Population, Poverty, and Politics in Middle East Cities

, ed. Michael Bonine (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997), p, 7; Martin Baldwin-Edwards,

Labour Immigration and Labour Markets in the GCC Countries: National Patterns and Trends

, Research Paper (London: Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2011), p. 9.

a

2005.

Also, as chapter 10 argued, most Middle Eastern countries have been paying far more attention to industrial development than to the development of the agricultural sector. Added stress on available food supplies increases the need for additional food imports, thus deepening international dependence on foreign suppliers and vulnerabilities to market fluctuations. Currently, the Middle East as a whole imports more than 60 percent of its food supplies. This reliance on food imports is expected to grow significantly over the next few decades.

13

The Arab world is the largest grain-importing

region in the world, and is, as a result, highly affected by spikes in global food prices. Six of the top ten wheat-importing countries in the world are located in the Middle East, with Egypt being the world’s single largest wheat importer. Increasingly, rising global food costs place severe pressures on the states and the peoples of the Middle East at both the national and household levels.

Table 16.

Age Structure in the Middle East, 2010 (% of population)

SOURCE:

World Bank,

World Development Indicators

, 2012 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2012), pp. 42–44; World Bank, Development Indicators Database, “Population Ages 0–14,” “Population Ages 15–64”, and “Population Ages 65 and Above,”

http://data.worldbank.org/topic/health

.

a

Includes South Sudan.

Moreover, high fertility rates appear to have negative effects at the household and individual levels. In particular, mothers with multiple

pregnancies run higher risks of disease or even death. And children, especially girls, who have multiple siblings are more likely to be deprived in various ways.

14

Equally consequential are the effects of high population growth rates on the uncontrollable growth of cities. An examination of the dilemmas associated with rampant and unplanned urbanization in the Middle East is beyond the scope of this book. But expanding urban populations, from high birthrates and also as a result of migration from rural areas into the cities, have created multiple problems in Middle Eastern (and other developing world) cities. From the megacities of Tehran to Istanbul, Cairo, and Algiers, to the smaller, “secondary” cities of Shiraz, Izmir, Ismailiyya, and Oran, and everywhere in between, urban infrastructure and services have been pushed to the breaking point and, in many instances, have collapsed under the pressure. Statistics cannot adequately capture the magnitude of the difficulties that cities and their inhabitants face. In the words of one observer, “The rapid urbanization and burgeoning city populations, similar to most of the Third World, have led to problems and to declines of quality of urban life. There are too many people, insufficient jobs, inadequate infrastructures, shortages of basic services, deficient nutrition, poor health, and a deterioration of the physical environment. Middle Eastern cities are in crisis.”

15

It is little wonder that the Middle East as a whole and its cities in particular are facing such acute crises of environmental degradation. In many of the Middle East’s larger cities, the air is often unbreathable and there are looming shortages of water for drinking and irrigation. If left unattended, environmental pollution is likely to have disastrous consequences for the Middle East.

Throughout the developing world, preoccupation with industrial development and the many struggles of daily life relegates popular concerns about the environment to the back burner. Especially in the inner cities and in other urban areas, where employment, housing, and other economic considerations are primary, protecting the environment is not a concern for the average person. Especially outside the oil monarchies, life for the popular classes can be harsh and constricting or at least beset with bureaucratic obstacles and other economic difficulties. Thus the average person is either unaware of the need to safeguard environmental resources or unwilling to assume the added economic costs of such an undertaking.

Environmental pollution takes a variety of forms, most commonly air, water, and soil pollution. Of these, air pollution has reached critical levels in many of the Middle East’s larger cities—such as Tehran, Istanbul, and Cairo—and has already had adverse consequences for public health, especially in the form of various respiratory ailments.

Air pollution has two main sources, both of which are plentiful in the Middle East (and elsewhere in the developing world): motor vehicles and industrial complexes and factories. As far as industrial complexes are concerned, most of the larger enterprises tend to employ older imported technology that is not always fully efficient and is often a major source of environmental pollution.

16

Air and especially soil pollution also result from the operations of small workshops and business establishments—coppersmiths, mechanics, furniture makers, and so on—of which every Middle Eastern city has thousands. Many of these semiformal businesses, often family owned and operated, are too small to enable their proprietors to invest in environmentally friendly technology and practices. Again, the question confronting these small business owners is one of priorities. Given the importance of ensuring the viability of the family business by maximizing profits and keeping overhead to a minimum, protecting the air or the ground from pollutants often becomes a nonissue.

Motor vehicles are an even bigger source of air pollution. For example, in Tehran, whose air is among the most polluted in the world, 71 percent of the air pollution comes from the city’s estimated two million cars.

17

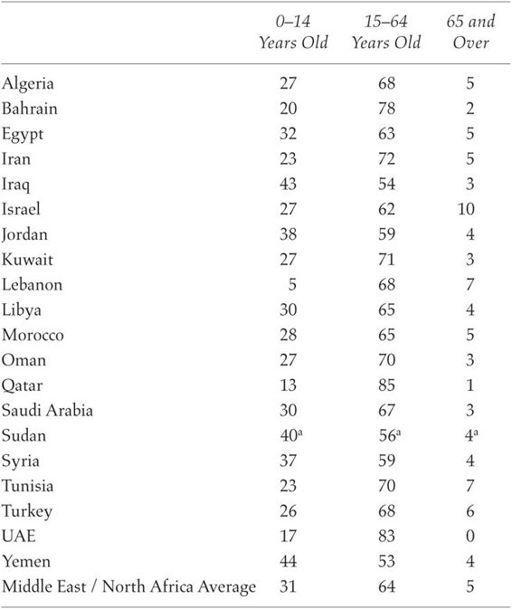

In the relationship between vehicles and air pollution, three factors are important: the sheer numbers of commercial and private vehicles in circulation, the toxicity and levels of their exhaust emissions, and the type of gasoline used. Recent decades have seen an astounding rise in the numbers of vehicles in the Middle East, so much so that traffic jams have become daily features of even smaller cities and towns throughout the region. For example, in 1974 there were 674,947 motor vehicles in operation in Turkey, but by November 2000 the number had jumped to 7,109,844, an increase of over 1,053 percent. During the same period, the number of buses increased by 551 percent and trucks by more than 412 percent. There were similar rises in the number of minibuses and small trucks, though by far the biggest rise, by some 1,400 percent, was in the number of passenger cars (table 17).

18

Added to these staggering numbers in Turkey and elsewhere is the continued and widespread use of leaded gasoline and diesel fuel by both passenger cars and trucks and buses throughout the Middle East, thus increasing the emission of harmful pollutants to the environment. Not surprisingly, as evident in table 18, the rate of harmful CO

2

emissions has been on the rise in almost all countries of the region.

Table 17.

Passenger Cars per 1,000 Individuals in Selected Middle Eastern Countries