The Modern Middle East (36 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

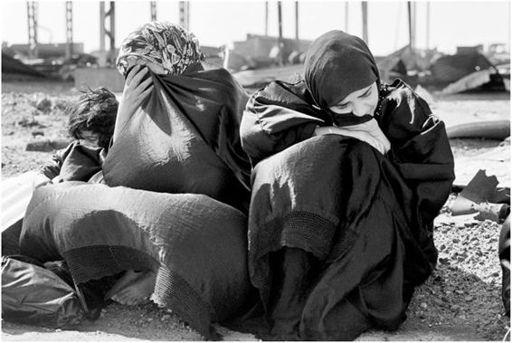

Figure 15.

Shiʿite Iraqi women mourning after the Gulf War in 1991. Corbis.

Operation Desert Storm was launched on January 16, 1991, with a massive aerial bombardment of Iraqi troop fortifications in Kuwait and throughout Iraq itself. Within a week, the Iraqi ground forces were decimated; the lucky ones who had the chance surrendered. Civilians were also hit, and the tragic bombing of a civilian shelter in Baghdad on February 13 led to the deaths of more than one thousand individuals. Washington claimed that the shelter had actually been a command and control facility.

38

To expand the war and to give credence to his anti-Israeli credentials, two days after the war started, on January 18, Saddam ordered the firing of twelve SCUD missiles at Tel Aviv. Four days later, another three were fired, this time killing three Israeli civilians and injuring scores of others. Uncharacteristically, Israel refrained from retaliating, impressed upon by the Americans that to do so would play into the Iraqi leader’s hands.

39

Five weeks after the aerial bombardment commenced, by which time little fighting spirit or capacity was left in the Iraqi forces, on February 24, the allied forces launched a multipronged ground offensive to dislodge what was left of Saddam’s forces. The road from Kuwait back into Iraq was cut off, and thousands of fleeing Iraqi troops were strafed and carpet bombed. For forty hours, Highway 80, the main link between Basra and

Kuwait, became the “highway of death” as orders were given, in the words of one U.S. officer, “to find anything that was moving and take it out.”

40

Finally, on February 27, Iraq accepted UN Resolutions 660, 662, and 674, which declared the Iraqi annexation of Kuwait null and void and deemed Iraq responsible for war reparations. The following day, both sides agreed to a cease-fire and hostilities ceased. The ground war had lasted only one hundred hours.

The end of the war brought Saddam one of the most serious challenges to his rule, not from his military commanders but from Iraq’s two main religious and ethnic minorities, the Shiʿites in the south and the Kurds in the north. Iraq is one of the Middle East’s most ethnically and religiously heterogeneous countries. Approximately 15 percent of Iraqis are ethnic Kurds. Moreover, Shiʿites constitute some 50 percent of the total population (the rest are about 40 percent Sunnis and 10 percent members of various Christian sects). Saddam’s relations with these two long-suppressed minorities had long been marked by friction and frequent bouts of violence.

41

As soon as the war ended and Baghdad’s central authority was at its nadir, they found the opportunity to rebel against Saddam and his state.

Two major uprisings started in the northern and southern parts of the country, where the Kurds and the Shiʿites predominated, respectively. The close proximity of the Shiʿite regions to Iran made their control more pressing for the government. Beginning in early March, Iraq’s regrouped forces, or what remained of them, launched a massive, brutal campaign to regain the south. Without the foreign assistance they had believed would be forthcoming, the Shiʿite rebels, with little military training and poorly equipped, quickly succumbed to Saddam’s forces. The Iraqi leader then turned his attention to the north, where, within weeks of the cease-fire, Kurdish rebels had gained control over twelve major towns and cities. By the month’s end, most of the north had also been recaptured, but not before an estimated one hundred thousand Kurds had been killed.

42

The international community’s condemnation of the massacre of Iraqi Kurds and their mass expulsion to Iran and Turkey was slow in coming, but it eventually did come. Soon the United States and Britain declared the establishment of a “safe haven” for the Kurds in northern Iraq and prohibited Iraq from flying fixed-wing aircraft, presumably jet fighters, in a southern and northern “no fly zone.” A de facto partition of Iraq went into effect, with the Kurdish north outside the government’s reach. Elsewhere in Iraq, however, Saddam’s rule remained unshakable. After years of bickering and finger-pointing, even the UN inspection teams, which had been sent

to supervise the dismantling of Iraq’s chemical weapons program, left the country because of the United Nations’ frustration in dealing with Baghdad.

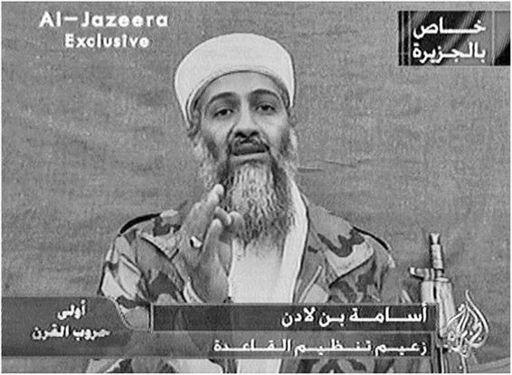

Figure 16.

A videotaped message from Osama bin Laden on Al-Jazeera. Corbis.

Once it was all over, Saddam Hussein was still standing, unfazed by the torment he had caused millions of people. Kanan Makiya, an Iraqi human rights activist, eloquently described the situation of Iraq after the Kuwait invasion:

The state that the Baʿth built in Iraq is far worse than one purely built on confessional or ethnic criteria. It is worse because it is consistently egalitarian in its hostility to everything that is not itself. The Baʿth demand from all Iraqis absolute conformity with their violence-filled, conspiratorial view of a world permanently at war with itself. Saddam Hussein invents and reinvents his enemies from the entire mass of human material that is at his disposal; he thrives on the distrust, suspicion, and conspiratorialism which his regime actively inculcates in everyone; he positively expects to breed hate and a thirst for revenge in Sunni and Shiʿi alike. As a consequence civil society, attacked from every direction, has virtually collapsed in Iraq.

43

Saddam’s “republic of fear” was not to last indefinitely, however. In 2003, the Iraqi regime succumbed to an all-out invasion and occupation of

the country by the United States. Under the banner of “war on terror,” President George W. Bush vowed to effect “regime change” in a country he had branded as a member of an “axis of evil.” By mid-2003, Saddam’s regime was a thing of the past, and Iraq was being run by American occupying forces.

THE POST—GULF WAR MIDDLE EAST

The Second Gulf War turned out to be a major watershed in the international relations of the Middle East. The Gulf War put a definitive end to any doubts concerning the death of Arab unity that had remained after Sadat’s defection from the “Arab cause” in the mid-to late 1970s. Pan-Arabism had suffered its first serious blow as far back as 1967, when the hollow rhetoric of Arab prowess cost each of the Arab participants large pieces of strategic territory. In hindsight, the wounds of 1967 turned out to be mortal, but their lethal effects took decades to materialize. Propaganda aside, the 1973 War was not really designed either to liberate the Palestinians or to vindicate the larger Arab nation. Its main goal was to enhance the position from which Egypt could negotiate the return of the Sinai and Syria could reclaim the Golan. By the time the 1970s were ending, the “focused system” that Nasser had so meticulously crafted had begun fragmenting along multiple axes.

44

Egypt was isolated; the oil monarchies sought shelter under the protective umbrellas of the United States; Syria, Iraq, and Libya, with their own internal discords, clung to an increasingly irrelevant rejectionist position in relation to Israel; Jordan was mastering its perennial balancing act; and Algeria and Morocco were grappling with their own mounting political and economic difficulties. Even the interlude of the 1980s, featuring the menace of the common Iranian enemy, failed to rekindle the once-vibrant united Arab alliance. Syria remained supportive of Iran throughout, lured by generous Iranian oil, and Libya and Oman also remained on friendly terms with Tehran’s radical clerics.

45

A measure of unity did develop in the cause of defending against Iran’s revolutionary Shiʿism, but that too dissipated within a couple of years. By 1990, the Arab world was arrayed against one of its own members. Iraq’s brutal “rape of a sister country” had to be stopped, no matter what the costs.

46

For the following decade, from 1991 until the fateful day of September 11, 2001, the Middle East was utterly fragmented, with each state motivated by self-interest and realpolitik. Even the alliance against Iraq during and immediately after the invasion of Kuwait, hailed by the few remaining Pan-Arabist apologists and hopefuls as a manifestation of Arab unity, came

together out of individual national-interest calculations rather than lofty ideals of defending Kuwait sovereignty, let alone saving the larger Arab family from a wayward son.

47

The Arab world of the 1990s suffered from internal discord, deepening dependence on international aid providers (Egypt and Morocco) and Western trading partners (the oil monarchies of the Arabian peninsula), and the sudden loss of the Soviet backing with which it could once balance out American influence (Syria). The United States was now the only game in town, and the American president, with his own domestic concerns, was determined to teach Saddam a lesson. Even Jordan’s refusal to join the international coalition against Iraq was motivated by self-interest. King Hussein, always one step ahead of his domestic and foreign opponents, knew well that he could not risk further antagonizing his subjects, who had only recently taken part in troubling “bread riots.” Among Americans, Jordan’s image was tarnished only temporarily, but among Arab peoples it was enhanced. President Bush’s much-heralded New World Order, for the Middle East at least, meant furthering national self-interest under the auspices of American hegemony.

The 1990s featured several significant events, each of which directly influenced Middle East diplomacy: the start of Iran’s Second Republic; Iraq’s de facto truncation; the Palestinian-Israeli signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993; Jordan’s 1994 peace treaty with Israel; the Algerian and Sudanese civil wars; and increasing competition over oil production and pricing within OPEC and between OPEC and nonmember oil producers such as Norway and Mexico. At the global level, meanwhile, the young Russian republic had its own economic and political growing pains, being preoccupied with a dysfunctional economy and an uncontrollable breakaway movement in Chechnya. The United States had neither a coherent vision nor a meaningfully articulated policy toward the Middle East. At best, Washington’s Middle East policy was geographically limited. Under the rubric of “dual containment,” the Clinton administration sought to narrow the options open to Iraq and Iran, America’s most vocal adversaries, in order to ultimately bring about a regime change in Baghdad and policy shifts in Tehran (especially toward the Palestinian-Israeli peace process).

48

Nevertheless, as chapter 9 demonstrates, the Clinton administration did become deeply involved in Palestinian-Israeli negotiations near the end of the decade.

There was, quite simply, no common cause around which to rally, no common enemy to unite against, no liberating hero to follow in unison. There were other, more substantial reasons for Arab unity’s demise. Three stand out. First, the Arab world of the 1990s lacked a hegemonic core under whose

auspices notions of Pan-Arabism could be reinvigorated and made accessible for the Arab masses at large. Since the 1950s, this historical role had been Egypt’s, as was almost natural given that country’s history, size, population, and heritage. But who would claim Arab leadership once Egypt was gone? And this was not just any ordinary departure. Sadat had

betrayed

the Arab cause; consequently the Arab League, the very symbol of Arab unity, was moved from Cairo to Tunis, and Egypt was expelled from it. Qaddafi did try to succeed Nasser, but he turned out to be too far from the Arab heartland, too erratic, and, once attacked by an American air raid in 1986, quickly silenced. Iraq would have been a far more likely candidate than Libya by virtue of its geographic position and its history, but its leader was too rapacious of the Arab family to be trusted. As for Saudi Arabia and its conservative Persian Gulf allies, whose economic power and closeness to the United States after the Gulf War were second only to Israel’s, they were in no position to initiate such a regionally hegemonic bid: besides money, they had almost none of the other necessary ingredients for such an endeavor—not enough manpower, no popularity outside their small countries, no salient heritage outside the Arabian peninsula (besides Islam), and no ideological tools.

49