The Modern Middle East (35 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

There were, of course, no winners in this bloody and devastating conflict. Not even Saddam or Khomeini could claim to have come out of the war as victors. The best each side could do was to exaggerate the damage it had inflicted on the enemy and deemphasize its own problems. Estimates put the total number of dead at 310,000: 205,000 Iranians and 105,000 Iraqis.

28

Altogether, nearly a million people were either injured or killed. Tens of thousands of soldiers on both sides were missing in action, and untold numbers were taken prisoner of war. Tehran is estimated to have had between 50,000 and 70,000 Iraqi captives. Iraq’s number of Iranian POWs, believed to be smaller, was never fully determined. The war also had incalculable economic costs, running into hundreds of billions of dollars. Excluding weapons imports, Iran is estimated to have spent between $74 and $91 billion to conduct the war, and Iraq between $94 and $112 billion.

29

Iraq’s economy was especially hard hit, as it was saddled with a crushing debt burden of around $89 billion, about $50 to $55 billion of which was

owed to Iraq’s allied neighbors to the south: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE. The cost of the necessary economic reconstruction in Iraq alone was estimated at around $230 billion.

30

Saddam Hussein, who had initially tried to insulate Iraq’s general population from the effects of the war by pouring money into the economy and promising a quick victory, was now faced with one of the gravest threats to his rule. Far from consolidating his hold on power, the war had spun out of control and had left his economy crippled. Early on, Iran’s ruling clerics had imposed rations on basic foodstuffs and banned the import of luxury goods, and they were thus better positioned to deal with the war’s adverse economic consequences. Far from undermining them, the war had strengthened their hold on the various levers of power, and its conclusion brought no credible threat to the clerical dominance of the state or to the overall legitimacy of the Islamic Republic. The predicament of Field Marshal Saddam Hussein was quite different. His three-week victory had turned into an eight-year nightmare, and he had nothing to show for it, only hundreds of thousands of dead and injured, billions of dollars in debt, and an economy scarcely able to absorb a demobilizing army of a million men. Saddam, the wily politician with a legendary survival instinct, needed to do something and do it quickly. Within two years, he undertook yet another international adventure. This time, he invaded Kuwait.

In the early-morning hours of August 2, 1990, approximately one hundred thousand Iraqi troops stationed near the Kuwait border marched south and, in a matter of hours, occupied the small sheikhdom and its capital city, Kuwait City. Almost all members of the Kuwait ruling family, including the emir, Sheikh Jaber al-Sabah, fled to Saudi Arabia. In a few hours, Saddam once again stood at the apex of power. He had handed his generals the quick and easy victory that had eluded them for eight years in the war with Iran, and this time the rewards—the looting and plunder of one of the world’s richest countries—were far more handsome and immediate. In less than a week, on August 6, Baghdad formally annexed Kuwait and declared it to be Iraq’s nineteenth province. While apprehensive about the ominous consequences of such an adventure, the people of Iraq celebrated Saddam’s seemingly awesome military prowess and his expansion of Iraqi territory. As foolhardy as the invasion might have seemed to the people of Iraq, few of them felt sorrow at the annexation of Kuwait, which many considered an

artificial, colonial creation, anyway. Kuwait now belonged to Iraq, and both firmly belonged to Saddam Hussein.

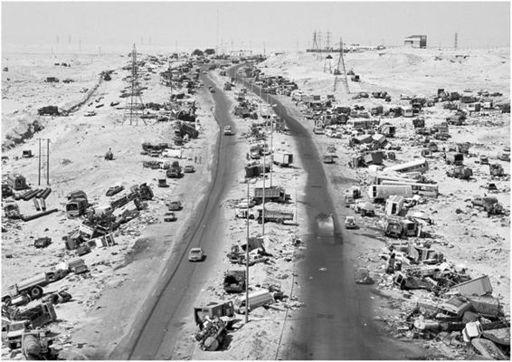

Figure 14.

Iraqi forces on the “highway of death.” Corbis.

The Iraqi invasion of Kuwait followed months of mounting tensions between Iraq, on the one hand, and its southern neighbors and the United States, on the other. Saddam apparently had started preparing for his southward invasion shortly after the formal conclusion of the war with Iran. By the time the Iran-Iraq War finally ended, the peoples of the two countries were both worn down and eager to get on with their lives. As chapter 5 demonstrated, the Iranian state, in response to a general desire for social and political relaxation, undertook an extensive program of economic reconstruction and ushered in what amounted to a Second Republic. Such was not the case in Iraq, however, for Saddam Hussein’s increasing political desperation ruled out domestic or diplomatic normalcy. For a few weeks in the spring of 1990, he floated talk of establishing democratic institutions, even going through the formalities of holding new elections to the National Assembly and inaugurating a new constitution. But democracy cramped Saddam’s style, and before long the new constitution was suspended and even the pretense of acting democratically was set aside. Instead, Saddam decided to divert domestic attention by pointing to a host of international conspiracies against Iraq, this time hatched not by the Iranians but by the

United States, Israel, and their Persian Gulf allies—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and the UAE.

Early in 1990, it is said, several foreign banks estimated that Iraq would finish the year bankrupt, owing some $8 to $10 billion to foreign creditors.

31

Not surprisingly, Saddam demanded that Kuwait pay Iraq $10 billion and cancel the debt it had accumulated during the war with Iran. At the meeting of the Arab Cooperation Council in February, he allegedly said, “I need $30 billion in fresh money, and if they don’t give it to me, I will know how to get it.”

32

While the saber rattling against Kuwait continued, Saddam turned his attention to Iraq’s other new enemies. He intensified his verbal attacks on Israel; charged an Iranian-born British journalist with spying and executed him; and accused the UAE and Kuwait of conspiring to harm Iraqi interests. Saddam shortly added territorial encroachments by Kuwait to his list of complaints.

Both the UAE and Kuwait undertook a number of conciliatory gestures—Kuwait, for example, announced it was cutting its oil output by some 25 percent—but to no avail. The Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, sought to act as a mediator and for a while appeared to have succeeded in easing Iraqi-Kuwait tensions. But Saddam had already made up his mind. By time the sun rose over the hot sands of Kuwait on the morning of August 2, Iraq’s army was in control of most parts of the small country. By two o’clock that afternoon, Kuwait City had fallen.

What ensued can best be described as a “war of miscalculations.” Every party in the unfolding conflict misread the situation and miscalculated the intentions, the resolve, and the strength of its opponent. The Iraqi leadership completely miscalculated the international community’s reaction to its occupation of Kuwait and its resolve to restore to the Kuwaitis their sovereignty. Baghdad also miscalculated its own strength, believing that it could inflict serious damage on the American-led military alliance. Moreover, Iraqi leaders misread the public mood in the United States, thinking that the memory of the Vietnam War would erode popular support for another open-ended military engagement. What Baghdad did not realize was that after some twenty years the memory of the Vietnam War had grown faint among the younger generation of Americans, for whom the Reagan-Bush years—punctuated by the release of the hostages in Tehran and military victories in Grenada and Panama—had resulted in a resurgence of patriotism and renewed national self-confidence. For an American public yearning for a victory that would decisively erase the painful memory of Vietnam, and for a Pentagon eager to display its new hardware and smart weapons, the prospect of fighting a distant, evil dictator was too tempting to

pass up. Saddam, as he himself soon discovered, was barking up the wrong tree. That Kuwait was one of the world’s largest producers of oil only added to the resolve of the hastily assembled “Allied Forces” to press for the small sheikhdom’s liberation.

As it turned out, the Iraqi armed forces were suffering from three basic, mortal flaws. First, throughout the war with Iran, the Iraqi military had exhibited weaknesses in planning, coordination, and strategy. By and large, these difficulties had arisen out of Saddam Hussein’s personal involvement in military decision making and his penchant for micromanaging his field commanders.

33

Second, the Iraqi army was far more battle-fatigued than battle-tested. The eight-year war with Iran, for which the Iraqis were neither economically nor psychologically prepared, had been a bigger drain on Iraq than either Saddam or his adversaries initially realized. When it came time to fight, Iraqi soldiers showed little actual resolve to stand firm, and many started surrendering en masse. Some even surrendered themselves to Western journalists whom they mistook for military personnel. The sustained and highly effective carpet bombing of Iraqi defenses in the first few days of the conflict quickly impressed upon the Iraqis that their new adversaries were far more deadly than the beleaguered, undersupplied Iranians they had faced earlier. Fighting the new enemy meant almost certain death and very little chance of survival, never mind victory.

A third, even more fundamental problem faced the Iraqis. Given that Iraq was a developing country, its military capabilities and ensuing military doctrine were largely defined by, and limited to, its overall position within the world system. For the Iraqis, it was one thing to take on another Third World country next door but quite another to pick a fight with a superpower. The Iran-Iraq War had featured heavy reliance on the infantry and on trench warfare. It had even seen many vicious hand-to-hand combats. But the new adversary relied not on infantry troops but on smart bombs released from hundreds of miles away. Trenches, troop concentrations, fortified bunkers, and other usual features of conventional warfare were now either obsolete or, in many instances, liabilities. In addition to heavy reliance on chemical weapons, many of Iraq’s battle successes against Iran had become possible only after the United States had shared satellite intelligence with the Iraqi military.

34

Now the former patron was itself the enemy. Saddam’s archaic military thinking did little to compensate for the comparative technological inferiority of his armed forces.

The lopsided nature of the conflict became apparent from its earliest days, when Iraqi defenses began collapsing like a house of cards. By the time the war was over, 142,000 tons of bombs had been dropped on Iraq and

Kuwait. More than one hundred thousand Iraqi soldiers were reported to have been killed, and another sixty thousand surrendered. Fully 3,700 Iraqi tanks were destroyed, as were 2,400 armored vehicles and 2,600 artillery pieces. The only way the Iraqi air force was able to escape widespread destruction was by flying the bulk of its jet fighters, as many as 135, to neighboring Iran after a hastily arranged cooperation agreement. By contrast, American casualties numbered no more than 148 dead, 35 of them by “friendly fire.” Fifty-seven American jet fighters and helicopters were also shot down, but not a single American tank was lost.

35

Eventually, the U.S.-led coalition grew to include some thirty-six countries, although its principal contributors remained the United States, Great Britain, and Saudi Arabia.

36

In theory, the United States and Saudi Arabia were in joint command of the operation. In reality, however, the whole affair was an American endeavor. An important aspect of the operation was that it featured the contributions of Arab states outside the Persian Gulf area, most notably Egypt, Syria, and Morocco. Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait placed Arab leaders in the unenviable position of having to either join the military coalition against Iraq or, by staying away, appear to support its occupation of Kuwait. The invasion of Kuwait, it must be remembered, was not all that unpopular among Arabs outside the Arabian peninsula. The invasion and the tensions leading up to it happened to coincide with the daily death of a number of Palestinians in street clashes with Israeli soldiers and a flaring up of the

intifada

movement. In light of America’s unwavering support for Israeli statehood and territorial expansion, the mounting of Operation Desert Shield seemed to most Arabs utterly hypocritical. The United States, many reasoned, had done nothing to stop or to reverse Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 or its continued expansion of settlements in Palestinian territories. But it was now rushing to the aid of a corrupt ruling family with vast oil resources. Throughout the region, from Jordan to Egypt and Morocco, anti-American, pro-Iraqi rallies were held, and political leaders had no choice but to let the people vent their anger. Popular passions were further inflamed when Saddam made his withdrawal from Kuwait contingent on Israel’s withdrawal from occupied Palestinian territories. Jordan’s King Hussein, sensing the depth of his people’s anger, declared his neutrality and offered to mediate between Saddam and the Kuwaiti ruling family. The PLO openly sided with Iraq. Most others, however, cast their lot with the United States, suppressed serious dissent at home, and, lured by the prospects of American economic assistance and subsidized oil from the Persian Gulf, sent troops to Saudi Arabia. In a contentious meeting held in Cairo a week after the

invasion, the Arab League voted twelve to three, with two abstentions, to join the Desert Shield alliance.

37