The Modern Middle East (33 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

The Iran-Iraq War was a bloody and devastating conflict, with an estimated one million dead and tens of thousands of prisoners of war captured by both sides. But as wrenching as the conflict was for Iranians and Iraqis, it had ramifications far beyond the two warring countries and their respective allies. The direction in which the war evolved and the circumstances under which it was concluded directly led to another war, this time resulting in Iraq’s invasion of its neighbor to the south, Kuwait. The “liberation” of Kuwait was carried out by a U.S.-led force of international allies under the banners of defending national sovereignty, upholding international law, and defeating aggression. Had the Iranians not violated international law themselves so blatantly by taking American diplomats hostage, perhaps the same level of moral outrage would have been directed at Iraq’s earlier invasion and occupation of Iranian territories. That Kuwait was very much pro-Western and a major producer of oil added force to the immorality of its occupation by Iraq. Ultimately, Iraq itself was invaded and the country was occupied, this time by an American-led “Coalition of the Willing” searching for weapons of mass destruction and promising to root out terrorism.

In some ways, the Iran-Iraq War appears to have been the last gasp of the dying phenomenon of Arab unity. A credible argument can even be made that such a phenomenon never existed beyond the tired and hollow rhetoric of leaders such as Nasser and Qaddafi. Empty as it might have been, the rhetoric served as a rallying cry for some, and, if nothing else, at times it succeeded in provoking panicked reactions by Israel and the West. Given the history of flimsy political institutions in the Middle East and the greater importance of personalities, rhetoric was a powerful political tool for both domestic constituents and international audiences. But with the death of Nasser and the dismantling of Nasserism at home and abroad, even the rhetoric of Arab unity started to die out, only occasionally sounding from the Libyan desert or from isolated and desperate Palestinian “revolutionaries.” Ironically, the religious character of the Iranian revolution did nothing to promote unity with the Iranians’ coreligionists in the Arab world. In fact, although the radical and radicalizing rhetoric of the revolution led to a brief episode of Arab unity, it only widened the rift between the Iranians and much of the Arab world.

As we have seen so far, much of the modern history of the Middle East has been shaped by the two seemingly contradictory forces of nationalism and Arab unity. In reality, these forces have been one and the same, differing only in the definition and scope they attach to the concept of nation. Is the Arab nation defined by virtue of its common language and literary tradition, its common culture and religion, or its common ethnic bonds? Or

is it fragmented into smaller units that are separated by borders drawn up in the period of colonialism? Whatever the depth and breadth of the Arab nation, for more than fifty years it has had to contend with diverse states, and the resulting entities have come to assume different characters, proud identities, and widely differing priorities. Emotional appeals to an overarching Arab nation have resurfaced only when they have suited the interests of specific Arab leaders at particular times: Nasser in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Qaddafi in the 1970s and 1980s, and Saddam Hussein in the 1980s. For many years, a genuine sense of commitment to the Palestinians, coupled with a need to blame domestic shortcomings on outside evils, made Israel the common enemy of many Arab states, thus keeping the ideal of unity alive in the collective memory of the Arab masses. But ideal and reality are two different things. As Israel proved again and again to be undefeatable, hopes for Arab unity grew increasingly dimmer and its promises more empty. When in the 1980s Iran emerged as a new common enemy, menacing Arab states near and far, the old ideal regained some life. Saddam, declaring himself the defender of the Arab nation, promised to slay the new enemy and to defend the honor and interests of all Arabs against Iranian ambitions. But as it turned out, he assumed that the Arab nation would be only a passive audience, viewing with admiration his state’s countless victories. Soon the Iraqi state would itself rampage through the Arab nation with the banner of Arab unity. What started as a tragic farce—the Iran-Iraq War—soon led to another wrenching charade, the Second Gulf War.

The cumulative effects of the two bloody Gulf Wars was a serious weakening of the regional state system in the Middle East. By the early 1990s, any measure of unity that had once grouped the Arab states in a “focused system” with a single goal was all but gone, and potential hegemonic powers like Egypt and Iraq had been weakened or isolated both within the region and internationally. The ensuing power vacuum was filled by the United States, now emboldened by the demise of the Soviet Union and the dawning of an American-dominated “New World Order.”

Power has its privileges, but it also attracts anger and resentment. A decade after the Gulf War ended, that anger manifested itself in a horrific attack on the American mainland by fanatics from the Middle East. September 11, 2001, marks a watershed in American diplomacy around the globe and especially in relation to the Middle East. This chapter examines the causes, consequences, and aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, especially the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq, as well as those of the two major military conflicts in the Middle East before that—the Iran-Iraq War and Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

On September 22, 1980, Iraqi forces invaded Iran at eight points on land and bombarded Iranian airfields, military installations, and economic targets.

3

Tensions had been building along the two countries’ shared border for some time, and there had been sporadic exchanges of fire since the previous February. These border clashes had come at a time of profound political uncertainty and chaos in both countries, especially in Iran, which was still boiling with revolutionary fervor. Tensions between the two countries continued rising throughout 1979 and 1980. On September 17 of that year, Saddam Hussein declared the abrogation of the 1975 treaty with Iran, which had marked the halfway point of the Shatt al-Arab waterway as the two countries’ common border, and claimed complete Iraqi sovereignty over the river. Shortly thereafter, on September 22, his forces invaded Iran.

The Iraqi invasion of Iran was a result of the interplay of four broad dynamics: (1) the domestic political predicament of the Iraqi president, Saddam Hussein; (2) the power vacuum in the new Islamic Republic; (3) the intensive propaganda of Iranian revolutionaries calling on the Arab masses to overthrow their leaders and to follow the lead of the Islamic Republic; and (4) Saddam’s regional ambitions as he sought to emerge as the new guardian of the Arab cause and the Nasser of his day. Each of these factors merits a closer look.

Saddam (1937–2006) had originally entered politics at the age of twenty, when he joined the Iraqi Baʿth Party. The Baʿth Party, which saw itself as one of the primary vehicles for fostering Arab unity, was originally established in Syria, the birthplace of its main theoretician and founder, Michel Aflaq. In the late 1950s, a group of middle-class Iraqis set up a separate Baʿth Party in Iraq. Although the two parties never formally merged, in the late 1950s and early 1960s they did, to some extent, coordinate their political and theoretical positions. By the late 1960s, Aflaq was finding himself increasingly at odds with the ideological officers running Syria, eventually leaving for Iraq in 1968. In many ways this was a result of the increasing factionalization of the Syrian Baʿth in the late 1960s and its division into various competing groups before Hafiz al-Assad effectively dominated the party and imposed on it a measure of unity. Tensions between the Iraqi and the Syrian Baʿth Parties were soon to develop, and in the early and mid-1970s each party accused the other of undue interference.

The 1958 coup that overthrew Iraq’s monarchy did little to improve the fortunes of the Iraqi Baʿth. In 1959, after mounting repression, a group of Baʿthists, including Saddam, was assigned to assassinate the dictator Abd al-Karim Qassem. Despite later glorifications of his role in the unsuccessful

attempt, it appears that Saddam actually botched the operation.

4

To avoid capture, he escaped to Syria, where he was warmly received by the Syrian Baʿth leadership, and from there to Egypt, where he received a high school diploma and briefly studied law at the University of Cairo. Egypt at this time was in the midst of the Nasserist phenomenon, and Nasser’s penchant for political theater and quest for Arab leadership appear to have left lasting impressions on the young Saddam.

5

In 1963, when Qassem was finally overthrown and the Baʿth briefly captured power, Saddam returned home, only to find himself on the margins of political life because of his long absence. After a short stint in prison for attempted murder, Saddam managed to rise quickly within the Baʿth hierarchy and was put in charge of its military organization. His rise through the ranks of the Baʿth owed much to his family ties to the party’s leader, Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr. When the Baʿth returned to power in 1968 and al-Bakr became president, Saddam’s political ascent picked up speed. He was made deputy chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), at the time the country’s most important decision-making body. A series of ruthless purges of the Baʿth soon followed, whereby potential opponents of al-Bakr and Saddam were eliminated one after another. By the early 1970s, Saddam had emerged as the second most powerful man in Iraq, in fact beginning to overshadow his older patron. He also meticulously cultivated a presidential image among the political elites and the larger masses by touring the country, signing international treaties on behalf of Iraq, and exerting his power both overtly and from behind the scenes. As two of his biographers write, “The voice was Bakr’s—but the hands were Saddam’s.”

6

On July 16, 1979, al-Bakr notified the nation of his retirement due to “health reasons” and gave his blessing to the succession of his deputy. Saddam “reluctantly” accepted the presidency. Few people bought the staged theatrics. A bloodless coup had occurred.

The conditions that allowed Saddam’s ascent to power, coupled with the political predicaments he faced as Iraq’s new president, were the primary reasons for his invasion of Iran the following year. The fact that Saddam Hussein had never formally served in the armed forces was symptomatic of a deeper divide between the Baʿth and the Iraqi military establishment. Throughout the late 1960s and 1970s, the Baʿth had increasingly asserted its dominance over the army, and in January 1976 al-Bakr appointed Saddam to the rank of lieutenant general (retroactive from July 1973).

7

Saddam’s assumption of power saw a concomitant rise in the size and powers of the Popular Militia, set up by the Baʿth as an ideological army and, in many ways, a rival to the regular armed forces. The ruthless purges of the

1970s also picked up pace with the new president’s inauguration, and some of the regime’s most recognizable figures were accused of treason or other antistate crimes and were eliminated. The purges within the RCC and the Baʿth were the most extensive, with some five hundred high-ranking party members said to have been executed within weeks of Saddam’s assumption of the presidency.

8

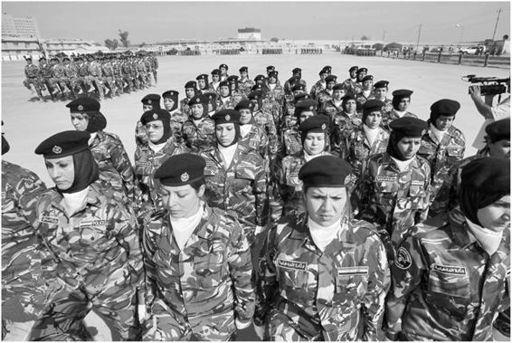

Figure 13.

Iraqi female police officers during their graduation ceremony. Corbis.

Authoritarian leaders seldom rule by repression alone. Depending on the larger circumstances in which they govern, they also try to gain some measure of popular legitimacy, however banal and fruitless such efforts might be. In Iraq, as in many other Middle Eastern countries, political leaders have often cultivated a sense of historic mission—an exaggerated account of the importance of their rule in relation to the country’s larger history—in order to enhance a supposedly popular mandate to govern and to “protect” the nation. Saddam’s image as such a “protector,” not just of the Iraqis but of the whole Arab nation, was bound to significantly broaden his mandate and, consequently, to expedite his determined quest for total political control. He made full use of the symbolisms involved, referring to the war with Iran as Saddam’s Qadisiyya, after the famous battle in which Muslim Arab forces conquered ancient Persia in 637

A.D.

9

All observers agree that at the time of its invasion of Iran, the Iraqi state was “brimming over with self-confidence and a sense of its own achievements.”

10

A quick

and decisive victory over a historic enemy, now crippled by its own internal squabbles, offered political rewards too tempting for Saddam to resist.

That the enemy was busy decimating its armed forces through revolutionary trials and speedy executions only helped expedite Saddam’s decision to attack. The political upheavals in Iran and the ensuing power vacuum were a second leading cause of the Iran-Iraq War. Soon after the revolution’s success, Iran’s new rulers launched a frenzied campaign to purge the ranks of the state of all nonrevolutionary elements. Within months, some twenty thousand teachers, eight hundred foreign ministry employees (out of a total of two thousand), and four thousand civil servants had been dismissed. The hardest hit were the armed forces, suspected of deep loyalties to the deposed shah; as many as two thousand to four thousand officers were quickly dismissed.

11

At the same time, some Iranian tribes, located mostly along the country’s northern, eastern, and western borders, began pressing for greater regional autonomy. The Kurdish challenge to the fledgling revolutionary government was especially serious, and armed clashes began to occur throughout Iran’s northwestern and western Kurdish regions. By late 1979, Iran’s continued detention of U.S. diplomats and the prolonged hostage crisis were quickly turning the country into a regional and indeed global arch-villain. To the seasoned, calculating Saddam Hussein, internal bickering among the revolutionaries, the youthful exuberance that publicly betrayed their inexperience, and the multiple domestic and international challenges they faced all made Iran’s new masters seem like easy prey.