The Modern Middle East (15 page)

Read The Modern Middle East Online

Authors: Mehran Kamrava

Tags: #Politics & Social Sciences, #Politics & Government, #International & World Politics, #Middle Eastern, #Religion & Spirituality, #History, #Middle East, #General, #Political Science, #Religion, #Islam

Figure 4.

Female members of the Iraqi Home Guard marching in Baghdad, 1959. Corbis.

This chapter examines the emergence and main features of four nationalisms in the Middle East: Zionism and early Israeli nationalism; early Palestinian nationalism; Egyptian nationalism under Nasser; and Maghrebi nationalism, as manifested in Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and, to a lesser extent, Libya. These were not, by any means, the only forms of nationalism in the Middle East in the early and mid-twentieth century. But they had the most profound influence, affecting the lives of millions not just in the countries where they flourished but in the whole region. In fact, Israeli and Palestinian nationalisms unleashed forces and led to developments that to this day continue to shape Middle Eastern and global political history. The rest of the chapter concerns the genesis and nature of these two contending national identities and their more immediate regional impact on Egypt and the rest of the Middle East. The subtle nuances and complexities of each of these national identities, and their contribution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, are discussed further in chapter 9.

ZIONISM AND THE BIRTH OF ISRAEL

The birth of the state of Israel was predicated on three key principles: (1) the constitution of the Jews as a distinct people with a unique identity, a nation; (2) the placing of this nation on a specific territory, the biblical Eretz Israel; and (3) the territorial and juridical independence of this nation in the form of a modern country. Since the late 1800s, and especially beginning in the early 1900s and culminating in 1947–48, these principles have formed the very core of Israel. The formation of a Jewish nation was facilitated by Zionism: the nation’s precise nature and character, and even its language (Hebrew), were deliberately articulated by individuals who set out to resurrect an ancient kingdom and its people in a new, modern form. Every nation needs a territorial reference point, however abstract in definition and reality, and for the Jewish nation that reference point was in Palestine. And for the Zionist project to be successfully completed, the Jewish nation needed political and territorial independence, so Israeli statehood was declared on May 14, 1948.

The early history of Zionism reads like the determined crusade of a handful of individuals, among whom Theodor Herzl, David Ben-Gurion, and Chaim Weizmann stand out. Within a matter of years, however, what had started as individual and at times highly criticized initiatives had snowballed into a large-scale migration of European Jewry into the Promised

Land. This migration was reinforced by growing, barbaric anti-Semitism and Jewish persecution, first in Russia, then in eastern and central Europe, and eventually in Germany. Although Zionism reached its most articulate and organized manifestation in nineteenth-century Europe, earlier versions of it, in the form of a belief in the chosenness of the Jewish people and their return to the land the Bible identifies as Eretz Israel, existed among Jews scattered throughout the world. This classical Zionism did not, however, provide much incentive for a return of the Jews to Palestine, as one of its central precepts was that the Jews would return to Zion only at the coming of the Messiah.

12

Nevertheless, the Jewish diaspora had some religious ties with the existing, though very small, community of Jews in Palestine. Estimates put the total number of Jews in the early 1800s at around 2.5 to 3 million, of whom some 90 percent lived in Europe and only about 5,000 lived in Palestine. Palestine itself had an approximate population of between 250,000 and 300,000, of whom an overwhelming majority were Sunni Muslim, some 25,000 to 30,000 were Christian, and an undetermined number, perhaps several thousand, were Druze.

13

Ironically, Zionism developed in a larger intellectual context that was initially opposed to the project of Jewish national assertion and uniqueness. Throughout the early 1800s, the dominant intellectual trend among the minority of learned European Jews who had not been consigned to the ghettos was the

haskala.

The

haskala

was a literary and cultural “enlightenment” calling for greater integration into the European cultural mainstream and reform of some of Judaism’s archaic rituals.

14

It was, in fact, a notable assimilationist, a prominent Austrian journalist named Theodor Herzl, who, upon witnessing the anti-Semitism of the Dreyfus affair firsthand, decided that the Jews’ salvation lay in a hastened return to a territory of their own, a Zion free of prejudice and discrimination.

15

In 1896, Herzl published a pamphlet called

The Jewish State,

in which he deplored the futility of assimilation, pointed to the pervasiveness of European anti-Semitism, and called for the establishment of a separate Jewish state based on Jewish identity and self-determination. The following year, in August 1897, he organized the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, which some two hundred delegates attended.

If

The Jewish State

was an attempt to articulate the characteristics of a nation, the First Zionist Congress and the ones after it represented that nation’s emerging state. Herzl’s book is concise, and its message, though simple, must have been compelling to its intended audience. “We are a people,” he wrote, “one people.”

We have honestly endeavored everywhere to merge ourselves in the social life of surrounding communities and to preserve the faith of our fathers. We are not permitted to do so. . . .

Let the sovereignty be granted us over a portion of the globe large enough to satisfy the rightful requirements of a nation; the rest we shall manage for ourselves. . . .

Let all who are willing to join us, fall in behind our banner and fight for our cause with voice and pen and deed.

16

Herzl did not create Jewish national identity; no one person creates a national identity from scratch. What he did was awaken what had lain dormant by pointing out, with contagious passion, that a separate, unique, identifiable Jewish nation did exist. “This pamphlet will open a general discussion on the Jewish Question,” he proclaimed.

17

And indeed

The Jewish State

did spark debate, in essence becoming, for the early generation of Zionists, a political and national manifesto.

The Basel conference gave organizational shape to Herzl’s utopia. Its declaration stated simply that “the aim of Zionism is to create for the Jewish people a home in Palestine secured by public law.” Herzl had already advocated as much. What the conference did was to initiate the necessary, concrete steps aimed at making the Zionist dream a reality. In this endeavor, it called for the implementation of four measures: promoting “the colonization of Palestine by Jewish agricultural and industrial workers”; organizing and uniting world Jewry through the creation of appropriate institutions; heightening “Jewish national sentiments and consciousness”; and securing international diplomatic support for the Zionist cause.

18

Implementing these goals was entrusted to a newly created World Zionist Organization, which became the seed of the future Jewish state. By the time the Second Zionist Congress was held in 1898, attended by about 350 delegates, the Zionist movement had grown significantly larger. Whereas only 117 local Zionist groups had been identified a year earlier, by 1898 their numbers had grown to over 900.

19

Other statelike institutions were quick to follow: a Zionist bank, the Jewish Colonial Trust, in 1899; a Jewish National Fund to finance land purchases in Palestine; and even internal divisions between Herzl’s largely secular, “political” Zionism and an emerging “cultural” Zionism calling for greater attention to the essence of Jewish identity and character.

20

The Jewish Agency, established in 1929 to manage the affairs of the Jewish community in Palestine, became something of a “state within a state.” Before long, a Zionist Federation of Labor, the Histadrut, a labor party called the Mapai, and a defense force, the Haganah, were established as well.

21

Within

this context successive waves of immigration to Palestine, called the

aliya,

were launched. The Jewish nation and the Jewish state were forming in a symbiotic, mutually reinforcing manner.

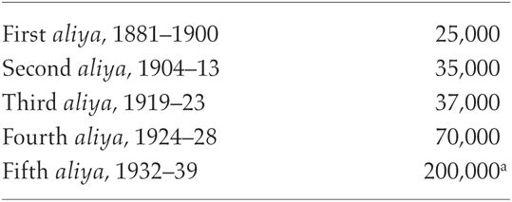

Table 1.

Jewish Immigration in Each

Aliya

SOURCE:

Data from Mark Tessler,

A History of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), pp. 60–61, 185, 208.

a

Does not include illegal immigration.

By the time the Basel conference ended in 1896, the first of five

aliya

was already slowly coming to an end (table 1). It had started in about 1881, and it lasted until 1900, during which time approximately twentyfive thousand mostly young, idealist Zionists immigrated to the Promised Land. But the experiences of this early group were less than successful, as many were new to farming and most were unfamiliar with actual living conditions in their new country. So unpleasant was the experience of the early arrivals that many returned to their countries of origin or emigrated to the United States.

22

Further, many early Zionists discovered, much to their surprise, that Palestine was actually densely populated and intensively cultivated and that available land was consequently expensive.

23

Nevertheless, by the end of the nineteenth century, the Jewish community in Palestine, the Yishuv, had grown to approximately fifty thousand individuals. During the second

aliya,

from 1904 to 1913, the Yishuv grew considerably, this time with significant support from the expanding network of Zionist organizations and with financial assistance from wealthy European philanthropists, chief among whom were members of Britain’s Rothschild family. The second wave of immigrants was mostly farmers and laborers. Since they had had little or nothing in their original countries to return to, they were determined to succeed in their new land. Thus the Yishuv increasingly assumed the characteristics of an integrated polity, more realistic and attuned to the conditions of its environment, and there to stay. Significantly, most of the leaders of the new state of Israel in 1948 would emerge from this

aliya.

24

The third

aliya,

generally dated from 1919 to 1923, brought thirty-seven thousand new immigrants to Palestine, expanding the Yishuv

to about eighty-four thousand. Another seventy thousand Jews immigrated to Palestine between 1924 and 1928, during the fourth

aliya,

this time mostly urban and mercantile in orientation. With them came the rise of Jewish urban settlements and an increase in the organizational strength of industrial laborers.

25

The fifth and last

aliya,

coming at the rise of fascism and the onslaught of the Second World War in Europe, occurred between 1932 and 1939, by the end of which the Yishuv’s population had grown to some 445,000, or about 30 percent of the total population of Palestine.

26

So far, there has been no mention of the Palestinians, the indigenous population of Palestine, who by 1947 numbered approximately 1.3 million. This omission is by design, for it was largely within a context of Palestinian nonexistence—a perception that the Promised Land was empty of a people with an identity or rights—that the European immigrants set out on their successive waves of colonization of Palestine. Zionism, it should be remembered, was a product of the intellectual and political environment of nineteenth-century Europe, one in which an industrially advanced, “civilized” Europe was almost universally assumed to have the right and indeed the responsibility to dominate and colonize the rest of the world.

27

The Zionists were a product of this intellectual milieu, although, as more time passed, for them colonization increasingly became a matter of life and death. This was a sentiment shared not only by Zionists but by notable non-Jewish Zionist sympathizers as well. “Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad,” wrote Lord Balfour, whose famous declaration paved the way for the official establishment of the state of Israel, “is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit this ancient land.”

28