The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade (87 page)

Authors: Susan Wise Bauer

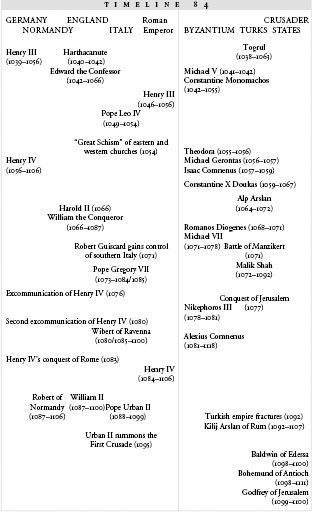

84.1: The Crusader States

The crusaders continued on towards Jerusalem. For a good cause, they could cope with being exhausted, outnumbered, sick, and hungry; but they objected to being manipulated.

The crusader army arrived at Jerusalem in early June of 1099. There they found a landscape as forbidding as Antioch’s. The summer days were hot, and water was scarce; the Turks had plenty of time to stop up the springs and foul the wells near the city, so that the crusader army would have nothing to drink. Trees, buildings, and all possible sources of timber near the city walls had been levelled. The pack animals, deprived of water, died and a “pestilential stench…rose from their decaying bodies.”

16

But Jerusalem itself did not possess Antioch’s frightening defenses, and the crusaders set doggedly to work. A siege camp was established around Jerusalem, and parties were sent far afield looking for wood. The attack on Jerusalem began on June 13. For three weeks, the crusaders battered the walls with ineffective siege machines built from twigs and brush.

When a fresh detachment of crusaders arrived by sea, Raymond of Toulouse directed that their ships be hauled aground and broken up for their wood. The siege towers built from the water-soaked timbers were rolled towards Jerusalem’s walls; under cover of crusader arrow-fire, the northern moat was filled in. The siege towers were pushed over the newly laid dirt. “The fighters in the siege engines had set on fire sacks of straw and cushions stuffed with cotton,” William of Tyre explains. “Fanned into a blaze by the north wind, these poured forth such dense smoke into the city that those who were trying to defend the wall could scarcely open their mouths or eyes. Bewildered and dazed by the torrent of black smoke, they abandoned the defense of the ramparts.” The attackers lowered wooden bridges to the tops of the walls and stormed across them into the city. Antioch had taken seven months to conquer; Jerusalem, barely thirty days.

17

Another massacre followed. “So terrible [was] the shedding of blood, that even the victors experienced sensations of horror and loathing,” says William of Tyre. “No mercy was shown to anyone, and the whole place was flooded with the blood of the victims. Everywhere lay fragments of human bodies.” Survivors were pulled from alleys, from closets, from cellars, and were killed by the sword or hurled from the walls.

The slaughter was in part the explosion of nearly two years of pent-up frustration with the heat, famine, disease, and misery of siege camps; in part, it was a calculated strategy to wipe out every trace of opposition. News had reached the crusaders that a Fatimid army was on its way from Egypt; the Fatimids, driven from Jerusalem by the Turks, were launching an attack to take it back.

18

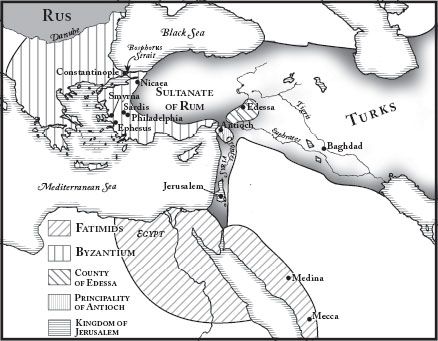

By the time the Fatimids arrived at Jerusalem’s wall on August 12, the city was completely under crusader control. Godfrey led the crusader army out from the city’s wall and drove the Egyptian army back without too much difficulty. The Egyptians retreated without mounting a second attack. Jerusalem had been taken; the goal of the First Crusade had been accomplished. Three Christian states, ruled by crusader nobles, now dotted the Muslim east: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Raymond of Toulouse was the obvious choice to rule the conquered city of Jerusalem. Unlike Antioch, Jerusalem had not been a Byzantine city before its conquest by the Turks, so there was no obligation to hand it back to Alexius. But Raymond declined to accept the title of king; the slaughter had left a poor taste in his mouth.

He probably hoped to be offered the job again with another title, perhaps that of “count” or “governor.” But like many good men, he was not particularly popular, and the second offer never came. Instead, Godfrey was offered the position and accepted it, ruling Jerusalem as its duke and protector.

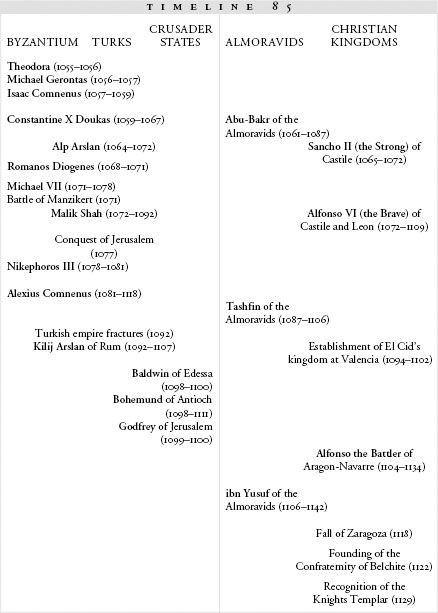

Between 1118 and 1129, the ideal of crusade is written into law

I

N

S

PAIN

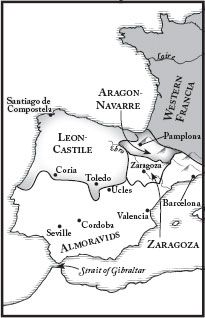

, Alfonso the Battler had been fighting for two decades against the Muslim Almoravids. This, as far as he was concerned, was also holy war. Recapturing Spain for Aragon-Navarre meant recapturing it for Christ, and it had been a long hard fight, complicated by his ongoing feud with his wife.

In 1118, a church council at Toulouse decreed that the capture of Zaragoza, the northernmost kingdom in the Almoravid realm, could be considered a crusade. This meant that helping to drive the Almoravid occupiers out of Zaragoza would be a righteous act, an accession of grace; one French account says that the pope himself promised forgiveness of sins to those willing to besiege the city.

1

Alfonso had been trying to capture Zaragoza for at least four years. The additional energy provided by the council finally tipped the balance. Noblemen from the south of Western Francia brought their private armies to help out, and the realm fell to the Christian armies in the fall of 1118.

The energies of the First Crusade had spilled across the west all the way into Spain, and had shifted the balance of power back towards the Christian kings. The Almoravid power in Spain began to diminish. The Almoravid ruler, Ali ibn Yusuf, remained in Marrakesh; he treated Spain like a distant outpost, and the Almoravid soldiers stationed there were less and less inclined to fight to the death to keep their land.

Meanwhile, Alfonso the Battler wrote the crusader status of his Christian armies into church law by founding a series of military orders; soldiers who joined them earned the status of monks, full-time servants of God. The Confraternity of Belchite was formed in 1122 to defend one particular area, south of the Ebro river: “Having been touched by divine grace,” Alfonso the Battler announced, in the order’s charter, “we have established through our imperial authority a Christian knighthood and a brotherly army of Christians in Christ, in Spain at the castle which is called Belchite…so that they may serve God there, and thereafter for all the days of their lives subdue the pagans.” Several other orders of Christian Knights followed, all devoted to keeping the Almoravids out of conquered territory.

2

At the same time, military orders were springing up in the east. The first and most powerful began in Jerusalem, where Godfrey had governed the city for barely a year before dying of typhoid. The Frankish crusaders still in Jerusalem had invited his brother Baldwin of Edessa to come and be crowned as the king of Jerusalem; this was a step up from count of Edessa, so Baldwin handed Edessa over to a distant cousin (also named Baldwin) and made his way to Jerusalem.

3

He fought a series of battles over the next eighteen years and expanded the Kingdom of Jerusalem well past the city’s borders; when he died in 1118, the same distant cousin who governed Edessa was crowned King Baldwin II of Jerusalem.

85.1: Alfonso’s Crusade

Now that the city was no longer in Turkish hands, more Christian pilgrims came to visit it; but all three crusader states were constantly under attack, and the journey was a perilous one. In 1119, the Frankish nobleman Hugh of Payens came to Jerusalem, searching for a way to better his soul. He decided that protecting pilgrims who were travelling unarmed from the coast to the city was a righteous mission, and over the next few years he recruited like-minded men to help him. They lived as monks: “not taking a wife,” wrote the twelfth-century patriarch of Antioch, Michael the Syrian, “not bathing, having no personal possessions whatsoever, but having everything in common.”

Like monks, they took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience; unlike monks, they carried arms. Their services were so greatly appreciated by travellers to Jerusalem that King Baldwin II decided to make provision for them: he “granted them a temporary dwelling place in his own palace,” says William of Tyre, “on the north side by the Temple of the Lord.”

4

They took their name, the Knights Templar, from this dwelling place.

*

In January 1129, Hugh of Payens travelled to the church council of Troyes to request formal recognition of his monastic order. The assembled churchmen approved of the order’s purpose, and the great monastic reformer Bernard of Clairvaux took it upon himself to write the order’s Rule. His Rule for the Knights Templar begins:

I exhort you who, up until now, have embraced a secular knighthood in favor of humans only, and in which Christ was not the cause, to haste to associate yourself in perpetuity with the Order…. In this, the order of knighthood, which, despising love of justice, did not strive to defend the poor or churches (which was its duty), but to rob, despoil and kill, has flowered again and revived.

5

This was exactly what Pope Urban II had hoped for: the redirection of violence into the paths of righteousness.

The founding of the military orders was the closing act in the drama begun by Constantine at the Milvian Bridge. Marching into Rome under the banner of the cross, he had taken a powerful and mysterious theology and bent it to his own purposes. It had promised unity; he needed unification. It had promised ultimate victory; he needed earthly victory, at once. It had promised an identity that transcended nationality and language; he needed to overcome nationalism. Most of all, he needed to convince his soldiers, the people of Rome, and the enemies who threatened him that he was driven by something higher and more noble than simple ambition.

Probably he needed to convince himself as well. Christianity gave Constantine freedom from guilt over his conquests, at the same time that it lent him the zeal he needed to pursue them. Seven hundred years later, the military orders did exactly the same thing for the men who joined them—and gave them a Rule to spell out precisely what they would gain. That marriage of spiritual gain and political power would shape the next five centuries; and the painful and protracted divorce between the two, the centuries after that.