Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (139 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Intestinal secretions

The principal constituents of intestinal secretions are water, mucus and mineral salts.

Most of the digestive enzymes in the small intestine are contained in the enterocytes of the walls of the villi. Digestion of carbohydrate, protein and fat is completed by direct contact between these nutrients and the microvilli and within the enterocytes. The enzymes that complete chemical digestion of food at the surface of the enterocytes are:

•

peptidases

•

lipase

•

sucrase, maltase and lactase.

Chemical digestion associated with enterocytes

Alkaline intestinal juice (pH 7.8 to 8.0) assists in raising the pH of the intestinal contents to between 6.5 and 7.5.

Enterokinase

activates pancreatic peptidases such as trypsin which convert some polypeptides to amino acids and some to smaller peptides. The final stage of breakdown of all peptides to amino acids takes place at the surface of the enterocytes.

Lipase

completes the digestion of emulsified fats to

fatty acids

and

glycerol

in the intestine.

Sucrase, maltase

and

lactase

complete the digestion of carbohydrates by converting disaccharides such as sucrose, maltose and lactose to monosaccharides at the surface of the enterocytes.

Control of secretion

Mechanical stimulation of the intestinal glands by chyme is believed to be the main stimulus for the secretion of intestinal juice, although the hormone secretin may also be involved.

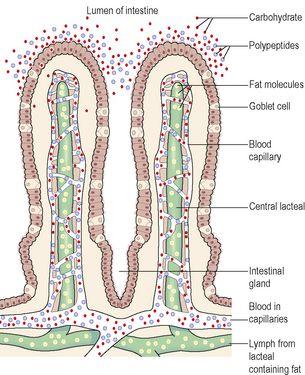

Absorption of nutrients (

Fig. 12.27

)

Absorption of nutrients from the small intestine through the enterocytes occurs by several processes, including diffusion, osmosis, facilitated diffusion and active transport. Water moves by osmosis, small fat-soluble substances, e.g. fatty acids and glycerol, are able to diffuse through cell membranes while others are generally transported inside the villi by other mechanisms.

Figure 12.27

The absorption of nutrients into villi.

Monosaccharides and amino acids pass into the capillaries in the villi. Fatty acids and glycerol enter into the lacteals where they are transported along lymphatic vessels and enter the circulation at the thoracic duct (

Ch. 6

).

Some proteins are absorbed unchanged, e.g. antibodies present in breast milk and oral vaccines, such as poliomyelitis vaccine. The extent of protein absorption is believed to be limited.

Other nutrients such as vitamins, mineral salts and water are also absorbed from the small intestine into the blood capillaries. Fat-soluble vitamins are absorbed into the lacteals along with fatty acids and glycerol. Vitamin B

12

combines with intrinsic factor in the stomach and is actively absorbed in the terminal ileum.

The surface area through which absorption takes place in the small intestine is greatly increased by the circular folds of mucous membrane and by the very large number of villi and microvilli present (

Fig. 12.26

). It has been calculated that the surface area of the small intestine is about five times that of the whole body.

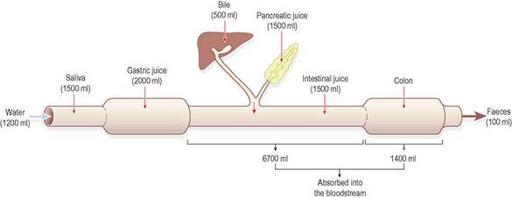

Large amounts of fluid enter the alimentary tract each day (

Fig. 12.28

). Of this, only about 1500 ml is not absorbed by the small intestine, and passes into the large intestine.

Figure 12.28

Average volumes of fluid ingested, secreted, absorbed and eliminated from the gastrointestinal tract daily.

Large intestine, rectum and anal canal

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

identify the different sections of the large intestine

describe the structure and functions of the large intestine, the rectum and the anal canal.

The large intestine is about 1.5 metres long, beginning at the

caecum

in the right iliac fossa and terminating at the

rectum

and

anal canal

deep in the pelvis. Its lumen is about 6.5 cm in diameter, larger than that of the small intestine. It forms an arch round the coiled-up small intestine (

Fig. 12.29

).

Figure 12.29

The parts of the large intestine and their positions.

For descriptive purposes the large intestine is divided into the caecum, colon, sigmoid colon, rectum and anal canal.

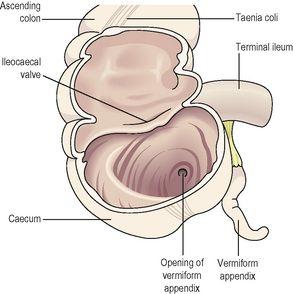

The caecum

This is the first part of the large intestine (

Fig. 12.30

). It is a dilated region which has a blind end inferiorly and is continuous with the ascending colon superiorly. Just below the junction of the two the

ileocaecal valve

opens from the ileum. The

vermiform appendix

is a fine tube, closed at one end, which leads from the caecum. It is usually about 8 to 9 cm long and has the same structure as the walls of the large intestine but contains more lymphoid tissue.