Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (140 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Figure 12.30

Interior of the caecum.

The colon

The colon has four parts which have the same structure and functions.

The ascending colon

This passes upwards from the caecum to the level of the liver where it curves acutely to the left at the

hepatic flexure

to become the transverse colon.

The transverse colon

This is a loop of colon that extends across the abdominal cavity in front of the duodenum and the stomach to the area of the spleen where it forms the

splenic flexure

and curves acutely downwards to become the descending colon.

The descending colon

This passes down the left side of the abdominal cavity then curves towards the midline. After it enters the true pelvis it is known as the sigmoid colon.

The sigmoid colon

This part describes an S-shaped curve in the pelvis that continues downwards to become the rectum.

The rectum

This is a slightly dilated section of the large intestine about 13 cm long. It leads from the sigmoid colon and terminates in the anal canal.

The anal canal

This is a short passage about 3.8 cm long in the adult and leads from the rectum to the exterior. Two sphincter muscles control the anus; the

internal sphincter

, consisting of smooth muscle, is under the control of the autonomic nervous system and the

external sphincter

, formed by skeletal muscle, is under voluntary control (

Fig. 12.31

).

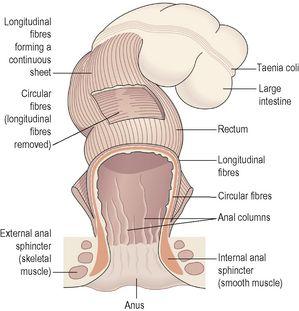

Figure 12.31

Arrangement of muscle fibres in the large intestine, rectum and anus.

Sections have been removed to show the layers.

Structure

The four layers of tissue described in the basic structure of the gastrointestinal tract (

Fig. 12.2

) are present in the caecum, colon, the rectum and the anal canal. The arrangement of the longitudinal muscle fibres is modified in the caecum and colon. They do not form a smooth continuous layer of tissue but are instead collected into three bands, called

taeniae coli

, situated at regular intervals round the caecum and colon. They stop at the junction of the sigmoid colon and the rectum. As these bands of muscle tissue are slightly shorter than the total length of the caecum and colon they give it a sacculated or puckered appearance (

Fig. 12.31

).

The longitudinal muscle fibres spread out as in the basic structure and completely surround the rectum and the anal canal. The anal sphincters are formed by thickening of the circular muscle layer.

In the submucosal layer there is more lymphoid tissue than in any other part of the alimentary tract, providing non-specific defence against invasion by resident and other potentially harmful microbes.

In the mucosal lining of the colon and the upper region of the rectum are large numbers of mucus-secreting goblet cells (see

Fig. 12.5B

) within simple tubular glands. They are not present beyond the junction between the rectum and the anal canal.

The lining membrane of the anal canal consists of stratified squamous epithelium continuous with the mucous membrane lining of the rectum above and which merges with the skin beyond the external anal sphincter. In the upper section of the anal canal the mucous membrane is arranged in 6 to 10 vertical folds, the

anal columns

. Each column contains a terminal branch of the superior rectal artery and vein.

Blood supply

Arterial supply is mainly by the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries (see

Fig. 5.45, p. 102

). The

superior mesenteric artery

supplies the caecum, ascending and most of the transverse colon. The

inferior mesenteric artery

supplies the remainder of the colon and the proximal part of the rectum. The

middle

and

inferior rectal arteries

, branches of the internal iliac arteries, supply the distal section of the rectum and the anus.

Venous drainage is mainly by the

superior

and

inferior mesenteric veins

which drain blood from the parts supplied by arteries of the same names. These veins join the splenic and gastric veins to form the portal vein (see

Fig. 5.47, p. 103

). Veins draining the distal part of the rectum and the anus join the

internal iliac veins

, meaning that blood from this region returns directly to the inferior cava, bypassing the portal circulation.

Functions of the large intestine, rectum and anal canal

Absorption

The contents of the ileum which pass through the ileocaecal valve into the caecum are fluid, even though a large amount of water has been absorbed in the small intestine. In the large intestine absorption of water, by osmosis, continues until the familiar semisolid consistency of faeces is achieved. Mineral salts, vitamins and some drugs are also absorbed into the blood capillaries from the large intestine.

Microbial activity

The large intestine is heavily colonised by certain types of bacteria, which synthesise vitamin K and folic acid. They include

Escherichia coli

,

Enterobacter aerogenes

,

Streptococcus faecalis

and

Clostridium perfringens

. These microbes are commensals, i.e. normally harmless, in humans. However, they may become pathogenic if transferred to another part of the body, e.g.

E. coli

may cause cystitis if it gains access to the urinary bladder.

Gases in the bowel consist of some of the constituents of air, mainly nitrogen, swallowed with food and drink and as a feature of some anxiety states. Hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane are produced by bacterial fermentation of unabsorbed nutrients, especially carbohydrate. Gases pass out of the bowel as

flatus

(wind).

Large numbers of microbes are present in the faeces.

Mass movement

The large intestine does not exhibit peristaltic movement as in other parts of the digestive tract. Only at fairly long intervals (about twice an hour) does a wave of strong peristalsis sweep along the transverse colon forcing its contents into the descending and sigmoid colons. This is known as

mass movement

and it is often precipitated by the entry of food into the stomach. This combination of stimulus and response is called the

gastrocolic reflex

.

Defaecation

Usually the rectum is empty, but when a mass movement forces the contents of the sigmoid colon into the rectum the nerve endings in its walls are stimulated by stretch. In the infant, defaecation occurs by reflex (involuntary) action. However, during the second or third year of life the ability to override the defaecation reflex is learned. In practical terms this acquired voluntary control means that the brain can inhibit the reflex until such time as it is convenient to defaecate. The external anal sphincter is under conscious control through the

pudendal nerve

. Thus defaecation involves involuntary contraction of the muscle of the rectum and relaxation of the internal anal sphincter. Contraction of the abdominal muscles and lowering of the diaphragm increase the intra-abdominal pressure (Valsalva’s manoeuvre) and so assist the process of defaecation. When defaecation is voluntarily postponed the need to defaecate tends to fade until the next mass movement occurs and the reflex is initiated again. Repeated suppression of the reflex may lead to

constipation

(hard faeces) as more water is absorbed.

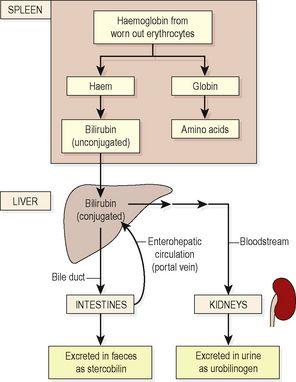

Constituents of faeces

The faeces consist of a semisolid brown mass. The brown colour is due to the presence of stercobilin (

p. 296

and

Fig. 12.37

).

Figure 12.37

Fate of bilirubin from breakdown of worn-out erythrocytes.

Even though absorption of water takes place in the small and large intestines, water still makes up about 60 to 70% of the weight of the faeces. The remainder consists of:

•

fibre (indigestible cellular plant and animal material)

•

dead and live microbes

•

epithelial cells shed from the walls of the tract

•

fatty acids

•

mucus secreted by the epithelial lining of the large intestine.

Mucus helps to lubricate the faeces and an adequate amount of dietary non-starch polysaccharide (NSP, fibre and previously known as roughage) ensures that the contents of the large intestine are sufficiently bulky to stimulate defaecation.

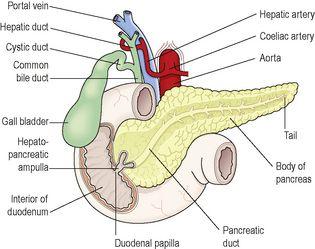

Pancreas (

Fig. 12.32

)

Figure 12.32

The pancreas in relation to the duodenum and biliary tract; part of the anterior wall of the duodenum has been removed.