Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (134 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

The pharynx is divided for descriptive purpose into three parts, the nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx (see

p. 236

). The nasopharynx is important in respiration. The oropharynx and laryngopharynx are passages common to both the respiratory and the digestive systems. Food passes from the oral cavity into the pharynx then to the oesophagus below, with which it is continuous. The walls of the pharynx consist of three layers of tissue.

The

lining membrane

(mucosa) is stratified squamous epithelium, continuous with the lining of the mouth at one end and the oesophagus at the other. Stratified epithelial tissue provides a lining well suited to the wear and tear of swallowing.

The

middle layer

consists of connective tissue which becomes thinner towards the lower end and contains blood and lymph vessels and nerves.

The

outer layer

consists of a number of involuntary muscles that are involved in swallowing. When food reaches the pharynx swallowing is no longer under voluntary control.

Blood supply

The blood supply to the pharynx is by several branches of the facial arteries. Venous drainage is into the facial veins and the internal jugular veins.

Nerve supply

This is from the pharyngeal plexus and consists of parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves. Parasympathetic supply is mainly by the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves and sympathetic from the cervical ganglia.

Oesophagus (

Fig. 12.14

)

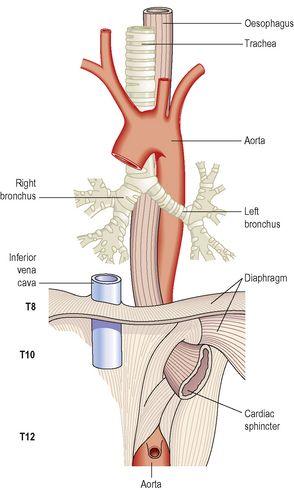

Figure 12.14

The oesophagus and some related structures.

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

describe the location of the oesophagus

outline the structure of the oesophagus

explain the mechanisms involved in swallowing, and the route taken by a bolus.

The oesophagus is about 25 cm long and about 2 cm in diameter and lies in the median plane in the thorax in front of the vertebral column behind the trachea and the heart. It is continuous with the pharynx above and just below the diaphragm it joins the stomach. It passes between muscle fibres of the diaphragm behind the central tendon at the level of the 10th thoracic vertebra. Immediately the oesophagus has passed through the diaphragm it curves upwards before opening into the stomach. This sharp angle is believed to be one of the factors that prevents the regurgitation (backflow) of gastric contents into the oesophagus. The upper and lower ends of the oesophagus are closed by sphincters. The upper

cricopharyngeal

or

upper oesphageal sphincter

prevents air passing into the oesophagus during inspiration and the aspiration of oesophageal contents. The

cardiac

or

lower oesophageal sphincter

prevents the reflux of acid gastric contents into the oesophagus. There is no thickening of the circular muscle in this area and this sphincter is therefore ‘physiological’, i.e. this region can act as a sphincter without the presence of the anatomical features. When intra-abdominal pressure is raised, e.g. during inspiration and defaecation, the tone of the lower oesophageal sphincter increases. There is an added pinching effect by the contracting muscle fibres of the diaphragm.

Structure of the oesophagus

There are four layers of tissue as shown in

Figure 12.2

. As the oesophagus is almost entirely in the thorax the outer covering, the adventitia, consists of

elastic fibrous tissue

that attaches the oesophagus to the surrounding structures. The proximal third is lined by stratified squamous epithelium and the distal third by columnar epithelium. The middle third is lined by a mixture of the two.

Blood supply

Arterial

The thoracic region is supplied mainly by the paired oesophageal arteries, branches from the thoracic aorta. The abdominal region is supplied by branches from the inferior phrenic arteries and the left gastric branch of the coeliac artery.

Venous drainage

From the thoracic region venous drainage is into the azygos and hemiazygos veins. The abdominal part drains into the left gastric vein. There is a venous plexus at the distal end that links the upward and downward venous drainage, i.e. the general and portal circulations.

Functions of the mouth, pharynx and oesophagus

Formation of a bolus

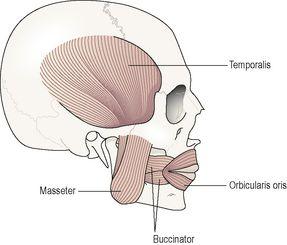

When food is taken into the mouth it is chewed (masticated) by the teeth and moved round the mouth by the tongue and muscles of the cheeks (

Fig. 12.15

). It is mixed with saliva and formed into a soft mass or bolus ready for swallowing. The length of time that food remains in the mouth depends, to a large extent, on the consistency of the food. Some foods need to be chewed longer than others before the individual feels that the bolus is ready for swallowing.

Figure 12.15

The muscles used in chewing.