Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (130 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Alimentary canal

Also known as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, this is a long tube through which food passes. It commences at the mouth and terminates at the anus, and the various parts are given separate names, although structurally they are remarkably similar. The parts are:

•

mouth

•

pharynx

•

oesophagus

•

stomach

•

small intestine

•

large intestine

•

rectum and anal canal.

Accessory organs

Various secretions are poured into the alimentary tract, some by glands in the lining membrane of the organs, e.g. gastric juice secreted by glands in the lining of the stomach, and some by glands situated outside the tract. The latter are the accessory organs of digestion and their secretions pass through ducts to enter the tract. They consist of:

•

three pairs of salivary glands

•

the pancreas

•

the liver and biliary tract.

The organs and glands are linked physiologically as well as anatomically in that digestion and absorption occur in stages, each stage being dependent upon the previous stage or stages.

Basic structure of the alimentary canal (

Fig. 12.2

)

Learning outcomes

After studying this section, you should be able to:

describe the distribution of the peritoneum

explain the function of smooth muscle in the walls of the alimentary canal

discuss the structures of the alimentary mucosa

outline the nerve supply of the alimentary canal.

The layers of the walls of the alimentary canal follow a consistent pattern from the oesophagus onwards. This basic structure does not apply so obviously to the mouth and the pharynx, which are considered later in the chapter.

In the organs from the oesophagus onwards, modifications of structure are found which are associated with specific functions. The basic structure is described here and any modifications in structure and function are described in the appropriate section.

The walls of the alimentary tract are formed by four layers of tissue:

•

adventitia or serosa – outer covering

•

muscle layer

•

submucosa

•

mucosa – lining.

Adventitia or serosa

This is the outermost layer. In the thorax it consists of

loose fibrous tissue

and in the abdomen the organs are covered by a serous membrane (serosa) called

peritoneum

.

Peritoneum

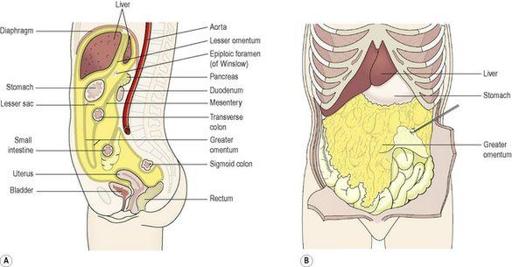

The peritoneum is the largest serous membrane of the body (

Fig. 12.3A

). It is a closed sac, containing a small amount of serous fluid, within the abdominal cavity. It is richly supplied with blood and lymph vessels, and contains many lymph nodes. It provides a physical barrier to local spread of infection, and can isolate an infective focus such as appendicitis, preventing involvement of other abdominal structures. It has two layers:

•

the

parietal peritoneum

, which lines the abdominal wall

•

the

visceral peritoneum

, which covers the organs (viscera) within the abdominal and pelvic cavities.

Figure 12.3

A.

The peritoneal cavity (gold), the abdominal organs of the digestive system and the pelvic organs.

B.

The greater omentum.

The arrangement of the peritoneum is such that the organs are invaginated (pushed into itself forming a pouch) into the closed sac from below, behind and above so that they are at least partly covered by the visceral layer, and attached securely within the abdominal cavity. This means that:

•

pelvic organs are covered only on their superior surface

•

the stomach and intestines, deeply invaginated from behind, are almost completely surrounded by peritoneum and have a double fold (the

mesentery

) that attaches them to the posterior abdominal wall. The fold of peritoneum enclosing the stomach extends beyond the greater curvature of the stomach, and hangs down in front of the abdominal organs like an apron (

Fig. 12.3B

). This is the

greater omentum

, and it stores fat, which provides both insulation and a long-term energy store

•

the pancreas, spleen, kidneys and adrenal glands are invaginated from behind but only their anterior surfaces are covered and are therefore

retroperitoneal

(lie behind the peritoneum)

•

the liver is invaginated from above and is almost completely covered by peritoneum, which attaches it to the inferior surface of the diaphragm

•

the main blood vessels and nerves pass close to the posterior abdominal wall and send branches to the organs between folds of peritoneum.

The parietal peritoneum lines the anterior abdominal wall.

The two layers of peritoneum are actually in contact, and friction between them is prevented by the presence of serous fluid secreted by the peritoneal cells, thus the

peritoneal cavity

is only a

potential cavity

. A similar arrangement is seen with the membranes covering the lungs, the pleura (

p. 243

). In the male, the peritoneal cavity is completely closed but in the female the uterine tubes open into it and the ovaries are the only structures inside (

Ch. 18

).

Muscle layer

With some exceptions this consists of two layers of

smooth (involuntary) muscle

. The muscle fibres of the outer layer are arranged longitudinally, and those of the inner layer encircle the wall of the tube. Between these two muscle layers are blood vessels, lymph vessels and a plexus (network) of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, called the

myenteric plexus

(Auerbach’s plexus,

Fig. 12.2

). These nerves supply the adjacent smooth muscle and blood vessels.