Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (118 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Obstructive lung disorders are characterised by obstruction of airflow through the airways. Obstruction may be acute or chronic.

Bronchitis

Acute bronchitis

This is usually a secondary bacterial infection of the bronchi. It is usually preceded by a common cold or influenza and it may also complicate measles and whooping cough in children. The viruses depress normal defence mechanisms, allowing pathogenic bacteria already present in the respiratory tract to multiply. Downward spread of infection may lead to bronchiolitis and/or bronchopneumonia, especially in children and in debilitated or elderly adults.

Chronic bronchitis

This is a common disorder that becomes increasingly debilitating as it progresses. Chronic bronchitis is defined clinically when an individual has had a cough with sputum for 3 months in 2 successive years. It is a progressive inflammatory disease resulting from prolonged irritation of the bronchial epithelium, often worsened by damp or cold conditions. One or more of the following predisposing factors are usually present:

•

cigarette smoking

•

acute bronchitis commonly caused by

Haemophilus influenzae

or

Streptococcus pneumoniae

•

atmospheric pollutants, e.g. motor vehicle exhaust fumes, industrial chemicals, sulphur dioxide, urban fog

•

previous episodes of acute bronchitis.

It develops mostly in middle-aged men who are chronic heavy smokers and may have a familial predisposition. Acute exacerbations are common, and often associated with infection. The changes occurring in the bronchi include:

Increased size and number of mucus glands

The increased volume of mucus may block small airways, and overwhelm the ciliary escalator, leading to reduced clearance, a persistent cough and infection.

Oedema and other inflammatory changes

These cause swelling of the airway wall, narrowing the passageway and obstructing airflow.

Reduction in number and function of ciliated cells

As ciliary efficiency is reduced, the problem of mucus accumulation is worsened, further increasing the risk of infection.

Fibrosis of the airways

Inflammatory changes lead to fibrosis and stiffening of airway walls, further reducing airflow.

Breathlessness (dyspnoea)

This is worse with physical exertion and increases the work of breathing.

Ventilation of the lungs becomes severely impaired, causing breathlessness, leading to hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure. As respiratory failure develops, arterial blood

P

O

2

is reduced (

hypoxaemia

) and is accompanied by a rise in arterial blood

P

CO

2

(

hypercapnia

). When the condition becomes more severe, the respiratory centre in the medulla responds to hypoxaemia rather than to hypercapnia. In the later stages, the inflammatory changes begin to affect the smallest bronchioles and the alveoli themselves, and emphysema develops (

p. 256

). The term

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD) is sometimes used to describe this situation.

Emphysema (

Figs 10.27

,

10.28

)

Pulmonary emphysema

Pulmonary emphysema usually develops as a result of long-term inflammatory conditions or irritation of the airways, e.g. in smokers or coal miners. Occasionally, it may be due to a genetic deficiency in the lung of an antiproteolytic enzyme, α

1

anti-trypsin. These conditions lead to progressive destruction of supporting elastic tissue in the lung, and the lungs progressively expand (barrel chest). In addition, there is irreversible distension of the respiratory bronchioles, alveolar ducts and alveoli, reducing the surface area for the exchange of gases. There are two main types and both are usually present.

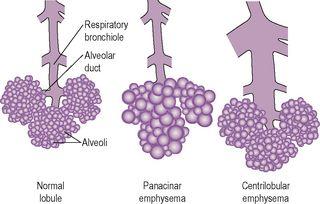

Figure 10.27

Emphysema.

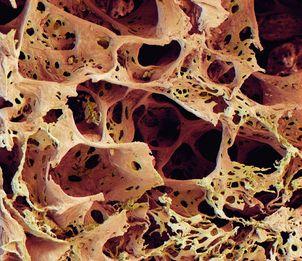

On microscopic examination, the lung tissue is full of large, irregular cavities created by the destruction of alveolar walls (

Fig. 10.28

, and compare with

Fig. 10.19

).

Figure 10.28

Coloured scanning electron micrograph of lung tissue with emphysema.

Panacinar emphysema

The walls between adjacent alveoli break down, the alveolar ducts dilate and interstitial elastic tissue is lost. The lungs become distended and their capacity is increased. Because the volume of air in each breath remains unchanged, it constitutes a smaller proportion of the total volume of air in the distended alveoli, reducing the partial pressure of oxygen. The consequence of this is reduction of the concentration gradient of O

2

across the alveolar membrane, therefore decreasing diffusion of O

2

into the blood. Merging of alveoli reduces the surface area for exchange of gases. Normal arterial blood O

2

and CO

2

levels are maintained at rest by hyperventilation, but as the disease progresses the combined effect of these changes may lead to hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension and eventually right-sided heart failure.

Centrilobular emphysema

In this form there is irreversible dilation of the respiratory bronchioles in the centre of lobules. When inspired air reaches the dilated area the pressure falls, leading to a reduction in alveolar air pressure, reduced ventilation efficiency and reduced partial pressure of oxygen. As the disease progresses the resultant hypoxia leads to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure.

Interstitial emphysema

Interstitial emphysema means the presence of air in the thoracic interstitial tissues, and this may happen in one of the following ways:

•

from the outside by injury, e.g. fractured rib, stab wound

•

from the inside when an alveolus ruptures through the pleura, e.g. during an asthmatic attack, in bronchiolitis, coughing as in whooping cough.

The air in the tissues usually tracks upwards to the soft tissues of the neck where it is gradually absorbed, causing no damage. A large quantity in the mediastinum may limit heart movement.

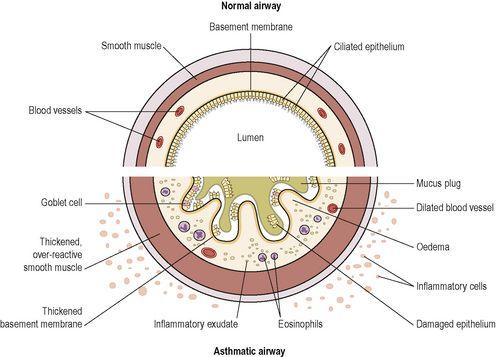

Asthma (

Fig. 10.29

)

Asthma is a common inflammatory disease of the airways associated with episodes of reversible over-reactivity of the airway smooth muscle. The mucous membrane and muscle layers of the bronchi become thickened and the mucous glands enlarge, reducing airflow in the lower respiratory tract. The walls swell and thicken with inflammatory exudate and an influx of inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils. During an asthmatic attack, spasmodic contraction of bronchial muscle (

bronchospasm

) constricts the airway and there is excessive secretion of thick sticky mucus, which further narrows the airway. Inspiration is normal but only partial expiration is achieved, so the lungs become hyperinflated and there is severe dyspnoea and wheezing. The duration of attacks usually varies from a few minutes to hours (

status asthmaticus

). In severe acute attacks the bronchi may be obstructed by mucus plugs, leading to acute respiratory failure, hypoxia and possibly death.

Figure 10.29

Cross-section of the airway wall in asthma.

Non-specific factors that may precipitate asthma attacks include:

•

cold air

•

cigarette smoking

•

air pollution

•

upper respiratory tract infection

•

emotional stress

•

strenuous exercise.

There are two clinical categories of asthma, which generally give rise to identical symptoms and are treated in the same way. Important differences include typical age of onset and the contribution of an element of allergy. Asthma, whatever the aetiology, can usually be well controlled with inhaled anti-inflammatory and bronchodilator agents, enabling people to live a normal life.

Atopic (childhood onset, extrinsic) asthma

This occurs in children and young adults who have atopic (type I) hypersensitivity (

p. 374

) to foreign protein, e.g. pollen, dust containing mites from carpets, feather pillows, animal dander, fungi. A history of infantile eczema or food allergies is common and there are often close family members with a history of allergy.

The same disease process occurs as in hay fever. Antigens (allergens) are inhaled and absorbed by the bronchial mucosa. This stimulates the production of IgE antibodies that bind to the surface of mast cells and basophils round the bronchial blood vessels. When the allergen is encountered again, the antigen/antibody reaction results in the release of histamine and other related substances that stimulate mucus secretion and muscle contraction that narrows the airways. Attacks tend to become less frequent and less severe with age.

Non-atopic (adult onset, intrinsic) asthma

This type occurs later in adult life and there is no history of childhood allergic reactions. It is often associated with chronic inflammation of the upper respiratory tract, e.g. chronic bronchitis, nasal polyps. Other trigger factors include exercise and occupational exposure, e.g. inhaled paint fumes. Aspirin triggers an asthmatic reaction in some people. Attacks tend to increase in severity over time and lung damage may be irreversible. Eventually, impaired lung ventilation leads to hypoxia, pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure.