Resurrecting Pompeii (26 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

Age distribution of the Pompeian sample, based on the pelvis

Age-at-death Number of individuals Percentage

1. Foetal

2. Infant

3. Juvenile

4. Adolescent

5. Indeterminate (adult)

6. Young adult

7. Adult

8. Mature adult

9. Older adult

0 0 0 0 12 6.12 25 12.75 79 40.31 17 8.67 45 22.96 9 4.59 9 4.59

Age distribution based on the Suchey–Brooks technique (note male and female scores have been pooled)

Phase 1 4 4.76

Phase 2 8 9.54

Phase 3 13 15.48

Phase 4 41 48.81

Phase 5 9 10.71

Phase 6 9 10.71

these individuals were identi fied as male. Fortyfive pelves, or 23 per cent of the sample, displayed pubic symphyseal faces that were consistent with an age attribution in the fourth decade of life. Of these, 26 were identified as male and 19 as female. The pelves of nine cases, or 4.6 per cent of the sample, were interpreted as having belonged to individuals in the fifth decade of life. Four of these were identified as males and five as females. Nine cases (4.6 per cent of the sample) were assigned to the sixth decade or older at the time of death. Five of these individuals exhibited male characteristics and four female.

Skull and teeth

The state of preservation of some skulls posed major dif ficulties for the determination of the age at death. The only criteria that could be employed to give an indication of age were ectocranial, or outer table, and endocranial, or inner table, suture closure, the development of the frontal sinuses, fusion of the basilar bone, the development of the Pacchionian depressions, tooth eruption and subsequent attrition. Of these, only ectocranial suture fusion and attrition could give an indication of the relative ages of the adults represented in this sample. Features like the development of the frontal

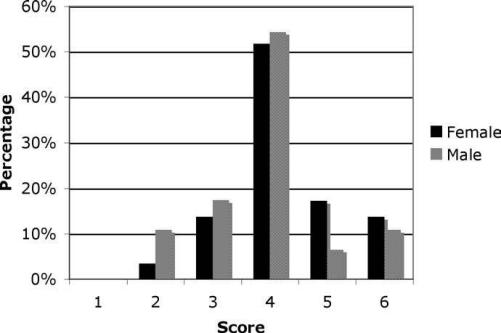

Figure 7.1

Figure 7.1Sex separated Suchey–Brooks scores for the Pompeian adult sample

sinuses and the fusion of the basilar bone, could only be used to discriminate between adults and juveniles. Like the pelvic age indicators, the cranial ageing criteria suggested a much higher proportion of adults than juveniles in the Pompeian sample.

The foetal skull is composed of a number of bones. The bones of the cranium are separate to enable some movement so that the skull can pass through the birth canal without damaging the brain. The cranial bones are separated by sutures. Growth of the skull occurs along these margins, which then fuse after growth has ceased. Age determination based on the order and degree of cranial suture closure was popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but fell from favour when studies revealed that these were unpredictably variable.

20

Since then endocranial, or inner table, suture closure has only been employed as a last resort in the absence of other skeletal remains.

Cranial suture closure was reassessed in the 1980s by Meindl and Lovejoy. Instead of using endocranial suture closure, which had previously been considered more reliable, they examined the ectocranial sutures, which are those that can be seen on the external surface of the cranium. They argued that these would be more useful for the calculation of age for older individuals as the ectocranial sutures close after the endocranial sutures. The authors stressed, however, that this technique should be used in conjunction with other ageing methods to produce an age based on a number of factors as there is no one reliable diagnostic feature for adult age-at-death.

21

The endocranial sutures were open in only 15.4 per cent of the sample of 123 skulls. Thirty-six cases or 29.3 per cent of the sample exhibited partially fused endocranial sutures and the remaining 68 cases or 55.3 per cent of the skulls had endocranial sutures that had substantially fused.

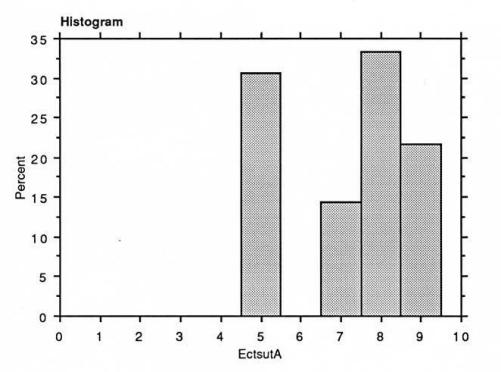

The ectocranial suture scores give some indication of the actual age of the adult sample. From the histogram (Figure 7.2) of the ectocranial lateralanterior suture closure scores (EctsutA), it is apparent that the majority of the sample (69.4 per cent) was aged between the ‘adult’ and ‘older adult’ age range. These scores are consistent with ages in a modern Western population of between the fourth and sixth decade or older. This technique does not provide information about individuals that have not yet reached the fourth decade of life. There were 34 skulls or 30.6 per cent of the sample that exhibited no sign of ectocranial suture closure and which, according to this system, could only be classified as being of indeterminate age.

The ectocranial vault suture closure (EctsutB) scores yield slightly different results, which is a reflection of the difference between the two scoring systems. Generally, more observations could be made using this method as it

Figure 7.2

Figure 7.2Estimated adult age-at-death based on ectocranial lateral-anterior suture closure scores (EctsutA)

involved parts of the skull that tended to have a higher survival rate. This can be seen in the larger number of cases that could be scored for EctsutB.

22

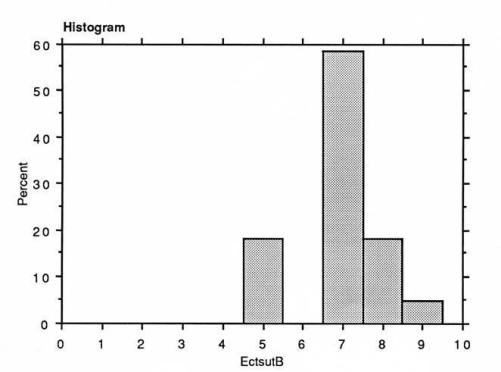

Similarly, inspection of the histogram (Figure 7.3) reveals that it was possible to make more observations of sutures as evidenced by the smaller number of indeterminate cases (18.2 per cent). Nonetheless, this method is not so useful for the determination of older ages as EctsutA is demonstrated by the highest frequency of age scores being in the ‘adult’ category and the lowest (just under 5 per cent) in the ‘older adult’ range.

The frontal sinuses first appear as extensions from the nasal cavity and increase in size with age. Development of the frontal sinus commences in foetal life but they do not begin to expand until about the middle of the fourth year of life. Their extension some distance into the supraorbital region of an individual is a good indication of adulthood. The sinus can continue to increase in size well into the fourth decade. The walls of the frontal sinuses become thinner in elderly people, which gives the impression of an increase in size.

23

Figure 7.3

Figure 7.3Estimated adult age-at-death based on ectocranial vault suture closure scores (EctsutB)

Fusion of the basilar bone

The fusion of the basilar portion of the occipital bone with the sphenoid is possibly the only example of cranial suture closure that occurs fairly consistently and can be used as a rough guide to separate adults from juveniles. In modern populations it is generally fused by 17 years of age in females and 19 years in males.

24

The scores for basilar fusion displayed a similar pattern to that observed with regard to the frontal sinus. Only two individuals (2.1 per cent of the sample) displayed a complete lack of fusion between the basilar portion of the occipital bone and the sphenoid, while there was partial fusion in three skulls (3.2 per cent) and complete fusion in ninety skulls (94.7 per cent).

Pacchionian depressions can be observed on the inner table of the skull on the frontal bone and on the parietals, on either side of the sagittal suture. These depressions become more distinct, deeper and more frequent with age and when well developed, suggest an older adult. Similarly, the impressions of the middle meningeal artery become deeper with advancing years.

25

Observations of the incidence and degree of development of Pacchionian depressions produced results that differed significantly from those of all the other features in that they appeared to be almost normally distributed throughout the sample.

26

Maxillary teeth

Tooth eruption

Tooth eruption is a good age indicator for sub-adults. The development and closure of roots subsequent to eruption is also a useful age indicator. Unfortunately, this could only be observed in the case of loose teeth, as no x-ray facilities were available.

27

The results for tooth eruption con firmed the evidence for a majority of adults in the sample. Of the 71 cases that could be scored, only four contained dentition that was consistent with that of an adolescent and 53, or 74.6 per cent, exhibited complete eruption of all the maxillary dentition. It was not possible to determine whether the remaining 14 cases were adult or sub-adult, either because of poor preservation of the maxillary area or because there was no sign of the third molars.

Tooth wear or attrition is entirely the result of environmental factors. In ancient populations it is usually interpreted as the result of eating unprocessed food or food that has been processed with millstones that contribute a certain level of grit into the diet. The use of basalt millstones (Figure 7.6) has obviously been a contributing factor to tooth attrition in the Pompeian sample. The quantity of certain foods consumed by an individual would influence the degree of attrition. Tooth wear can also result from industrial use of the teeth, poor occlusion or even from habit as in the case of bruxism, or tooth grinding. The early stages of attrition only affect the enamel of the tooth but over time, continual wear can lead to exposure of the dentine and even the pulp cavity in very severe cases, though generally this is protected by the formation of secondary dentine. It is possible for the entire enamel crown to be worn away (Figures 7.4 and 7.5).

28

Several factors contributed to the diminution of the value of attrition as an age indicator for the Pompeian population. First, the disarticulation of the mandibles, which generally could not be reunited with the skulls, meant that the state of occlusion for each individual could not be assessed and this could not be factored into interpretation. The other major problem was the fact that few of the mandibles or maxillae contained a full complement of teeth. In cases of incomplete dentition, the most conservative score was used. Because of the minimal number of cases of total tooth retention, these techniques were more valuable as a means of seriating the data than as absolute age indicators.