Resurrecting Pompeii (11 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

The idea that the wall paintings re flect the features of the ancient Pompeians has persisted, as exemplified in the writing of Conticello, a previous Superintendent of Pompeii, who described the various indigenous

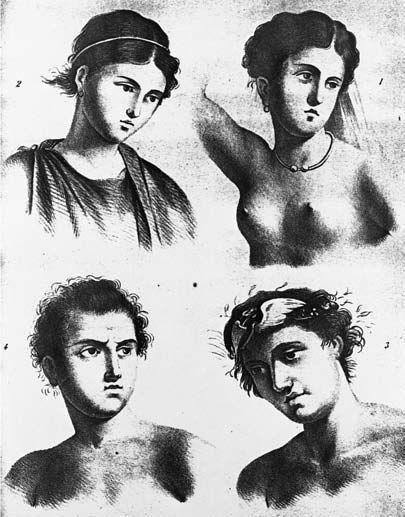

Figure 3.1

Figure 3.1Illustration of the Pompeian Type as identified by Nicolucci from Pompeian wall paintings (Nicolucci, 1882, 24–25)

components that he considered were detectable in the wall paintings from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor in Boscoreale: ‘The Campanian element is seen in the soft, flabby physiognomies, the large dark eyes, the familiar facial features and the indolence of the heavy, thick-skinned bodies that lack inner tension.’

19

There has been considerable discussion about whether Pompeian paintings comprise portraits or idealized images.

20

It has been suggested that whilst portraits can be identified amongst Pompeian wall paintings, for example that erroneously identified as Paquius Proculus and his wife, the term cannot be used in the modern sense. Current wisdom is that portraits were supposed to be read, first, in terms of the context in which they were found and, second, in terms of the style and the attributes associated with the subject. These attributes provided information about the profession and status of an individual, as can be seen in the presumed portrait of Paquius Proculus, which shows the subject holding a writing implement, waxed tablets and a scroll, thus indicating literacy.

21

It is difficult to determine whether these portraits are actually representational. It does, however, seem unlikely that the illustrations Nicolucci chose for his work represent specific individuals or even generalized images of members of a population. The suggestion that the works of Renaissance artists reflect regional types can also be questioned. A comparison, for example, between the work of Leonardo da Vinci and Botticelli, two fifteenth-century artists who were both trained in Florence under the same master, Verrocchio, demonstrates that they were not painting the same ‘types’ of individuals. The features of Leonardo’s so-called Mona Lisa, which is purported to be a portrait of a Florentine woman, are demonstrably different to those of the women in Botticelli’s Primavera.

22

It is rather simplistic to assume that idealized models of women owe more to regional form than the idiosyncratic personal preferences of the artist. As can be seen from Conticello’s description, the interpretation of indigenous types from paintings appears to be based on preconceived ideas, like the notion that South Italians are dark and swarthy.

Nicolucci considered that four of the hundred skulls he studied presented a type, which he described as very close to that of the ancient Romans. All four were male, two being mesocephalic and two brachycephalic. According to Nicolucci, there were a number of characteristics that suggested a Roman origin for these crania. He determined that these four crania were fuller, anteriorly wider and more flattened than the other Pompeian heads. The brows and orbits were larger, and the jaws almost circular in form. The cranial capacity was equal to the mean of the Roman crania, which was calculated at about 1525 cc. He also observed what he considered to be Pompeian traits on these skulls, such as the lack or minimal protrusion of the frontal sinuses, the lack of or slight depression of the nose at its root and ‘the singular delicacy of all the contours of the skull’. He speculated that these people were not purely Roman but instead were the result of intermarriage between Romans and the indigenous Pompeian population. He also proposed as an alternative explanation, that fusion of types he observed might relate to the common origin of the Roman and Campanian populations.

One skull in particular claimed Nicolucci ’s attention. It was interpreted as that of a young male, notable in Nicolucci’s eyes for its considerable length and laterally protuberant zygomatic bone as well as for its smooth temples, prognathic maxilla and large and heavy mandible. The facial angle was found to be about 70 degrees. He calculated its cephalic index to be 68.8 and its cranial capacity to be just below 1351 cc. Nicolucci considered that this skull had no European parallel and that its characteristics could only be seen in the so-called negroid type associated with people from the African continent. The principal measurements of this skull were compared with the mean measurements of the dolicocephalic male Pompeian skulls. Nicolucci found the proportions of this skull to diverge significantly from those of the other Pompeian dolicocephalic skulls and all other Italian dolicocephalic skulls.

Nicolucci primarily based his classi fication of this skull on a figure in Retzius’

Ethnologische Schriften

as well as Hartman’s

Die Nigritier

since he did not have any African skulls for comparison. The figure Nicolucci consulted in Retzius’ publication was of an old Abyssinian who had been in the service of a European family. He considered that the proportions of the different parts of the head in Retzius’ publication corresponded very approximately with those of the skull from Pompeii. He suggested that there was, therefore, a high probability that the cranium in the Pompeian sample belonged to an individual from this region. Nicolucci did not consider the discovery of a ‘negro’ skull in an ancient Roman city at all remarkable since slaves from conquered countries were a well-known element of the Roman economy. In addition, he cited the identification of ‘negro’ features on a plaster cast of a victim stored in the museum in Pompeii.

Nicolucci concluded that the population of Pompeii in

AD

79 was heterogeneous, incorporating an indigenous population along with people from other provinces, such as Rome, and from countries beyond Italy, as evidenced by the skull he identified as ‘negroid’. He noted that though there were a number of cranial forms as reflected by the presence of the three types of cephalic index, they combined to form a specific Pompeian ‘type’ which was comparable to that identified as the ancient Oscan ‘type’ in other parts of Southern Italy.

23

Nicolucci ’s work differed from that of his predecessors in that he chose to work on a large sample of material. The work that preceded him was often antiquarian in nature, generally involving only a few examples from which conclusions were drawn or single specimens that were thought to be of interest for some specific feature, such as pathological change. Like most other nineteenth-century physical anthropologists, Nicolucci considered that it was possible to characterize a population solely on the basis of skull shape (see below). He made a battery of measurements on an apparently statistically valid sample. His statistical treatment of the data was very basic, mainly involving the determination of means for specific measurements and indices.

The most signi ficant contribution Nicolucci made to physical anthropology was the publication of the raw data he collected so that it could be compared to and incorporated into contemporary skeletal studies (see below and Chapters 6, 7 and 9). The interpretations he made from this data are generally not relevant in terms of modern skeletal studies as most of the notions he held about the value of craniometry for the determination of European population types are no longer considered valid. For example, the majority of the differences that Nicolucci invoked to separate the Pompeian from the Roman ‘type’ are almost certainly too superficial to be more than artefacts.

A point to consider when assessing a nineteenth-century analysis of skulls is the demonstrated tendency for such works to be used to reinforce commonly held beliefs about the status of different ‘races’ and sections of society. Nicolucci’s work is distinguished by the absence of value judgements, especially when compared to the work of Linnaeus, which provided the basis for his study.

24

It is notable that the cranial capacity of the skull Nicolucci interpreted as a ‘negro’ male is much lower than the male mean for the Pompeian sample. In fact, it is barely higher than the mean that he calculated for the female sample. Most nineteenth-century scholars believed that cranial capacity was a reflection of the size of the brain and, hence, intellectual capability. Groups were ranked hierarchically by the means of their cranial capacity. Such an approach can be seen in the work of Morton. This notion has since been discredited as no evidence has been found to link brain function with size.

25

In the same vein, the difference between the male and female means for cranial capacity is so great that, even though it is not stated in Nicolucci’s paper, it is possible that this feature was used as a major criterion for sex determination, as it was commonly assumed that female cranial capacity is significantly lower than that of males (Chapter 6).

Nicolucci did not state what he used to measure cranial capacity. It has been demonstrated that there can be considerable variation in this measurement as a result of the use of different materials; for example in 1841 Morton revealed that white mustard seeds produced more variable results than lead shot. Morton observed differences of up to four cubic inches on remeasurement of skulls with mustard seeds and a margin of error of only one cubic inch with one eighth inch diameter lead shot.

Gould considered that it was possible that Morton may have exercised unconscious bias in the interpretation of measurements made before he forsook mustard seeds. It is possible that Morton unintentionally favoured results which reinforced his preconceived notions of what the cranial capacity ranking of the skulls should have been. That any bias on his part was unconscious was borne out by the fact that Morton presented both his raw data and described his methods.

26

Nicolucci’s work is harder to scrutinize as he did not document his materials and methods. While it is likely that the interpretations of the skulls were directly related to the cranial capacities he calculated, consideration should be given to the possibility that Nicolucci’s method of measurement could have unconsciously provided him with the results he expected for both sex and ‘race’.

To appreciate Nicolucci ’s contribution to our understanding of the Pompeian population, his work needs to be viewed in the context of the development of the discipline of physical anthropology. From the eighteenth to the second half of the twentieth century, the main focus of population studies, based on human skeletal remains was taxonomic, where human groups were separated into so-called ‘races’ by anthropologists, including Nicolucci, Angel and Fürst. The word ‘race’ was initially introduced into scientific literature as a zoological term by Buffon in 1749. ‘Race’ was first used in a classificatory sense for humans in 1775 by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a German doctor and anatomist who is credited as a pioneer in physical anthropology and founder of craniometry. The impetus for the taxonomic approach to describe human variation was the work of Linnaeus. Traditionally craniometric analysis of the skull was used to provide this information, though non-metric traits could also be used as population markers.

27

Blumenbach considered race to be a useful tool for classi fication. He did not invest too much meaning into his system as he considered it to be arbitrary. This appears to have been a reasonable approach, which is borne out by recent studies. In general, he described human variation as continuous, with relatively trivial differences between groups. The classification of people into specific groups is dependent on the criteria that are selected. Various criteria, such as retention of the enzyme lactase into adulthood, the presence of the gene for sickle cell anaemia or different fingerprint patterns all produce sets of groups which are composed of totally different collections of people. Despite Blumenbach’s attitude to race, the concept became politicized. In the nineteenth century, there was a tendency to use racial classification to rank different human populations, usually with the group with which the investigator was affiliated at the apex. The Parisian Société d’Anthropologie, founded by Paul Broca in 1859, institutionalized craniology as the basis of anthropological research.

28

Nineteenth-century racial classification systems were based on several assumptions; most importantly, that skeletal traits were immutable and that the divisions between races were hierarchical. The notion of immutability was challenged by Boas in 1911 when he published his findings of cephalic index measurements, a popular race descriptor, on the children of European immigrants to America. He discovered that environment played a significant role in the determination of this index, as it varied between the children and their parents. Subsequent studies in different parts of the world have confirmed the plasticity of certain traits as a result of altered environment.

29

The whole concept of racial classi fication was reassessed at the conclusion of World War II and in the following years, when it became apparent that it had been used as a justification for genocide. The agenda of bioanthropological studies was reconsidered and the majority of scholars abandoned racial studies. The issue of the validity of this form of classification, especially for the so-called European races, was discussed at length. Some anthropologists, like Coon and D’Amore

et al

., continued to use the racial classification systems, even though most scholars would no longer consider them appropriate, especially for the description of European populations.

30

Biologically, different races are categorized on the basis that they display a tendency to become separate species. One of the features of human populations is that there is no evidence that speciation is occurring. This can be demonstrated by the fact that individuals from populations that have been geographically and temporally separated for many millennia can reproduce and produce fertile offspring. It is now recognized that there are no human ‘races’ and that population differences are not discrete but continuous. The use of the term ‘race’ is no longer considered acceptable by most scholars as it is biologically inappropriate. In addition most researchers would prefer to distance themselves from the nefarious applications of racial studies in the past.

31

Nonetheless, there are, albeit superficial, differences between populations that can provide clues to origin. These result from various processes, including adaptation, genetic drift, small foundation populations and inbreeding groups. While it may seem precious to use other descriptors, like ancestry or population affinities, for current studies that attempt to identify different human groups, they do reflect a more appropriate scientific terminology.