Resurrecting Pompeii (22 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

The determination of sex from adult skeletal remains is based on the assumption that the bones of males are generally both more robust and larger than those of females.

13

There are several factors which contribute to these differences. Hormonal changes at the onset of puberty are perhaps the most important. They result in an increase of androgens in males and oestrogens in females. Androgens help males develop bone and muscle more easily than females.

14

Health, diet and lifestyle also determine the degree of muscle and bone development in individuals.

15

Sexual dimorphism can, for example, be a reflection of the distribution of labour in a society and thus can vary considerably between populations. The bones of females can become extremely robust when they engage in heavy labour. In the absence of complete skeletons, bones from such individuals can be difficult to differentiate from those of males. For example, remarkably robust pre-Hispanic skeletons from Tlatilco were only identifiable as female on the basis of their unequivocally female pelves.

16

The contribution of nutrition and health to the degree of sexual dimorphism in a population has been the subject of some controversy. It does appear that environmental stressors have a greater effect on males than females, which can lead to a decrease in skeletal sexual dimorphism, observable as a decrease in male height and robusticity.

17

Genetic population differences may also account for differential sexual dimorphism.

18

Some populations are relatively more robust than others, e.g. the skull of a female Indigenous Australian may be more robust than that of an Asian male. Conversely, the postcranial skeleton of an Indigenous Australian tends to be far more gracile than that of a European. However, due to the multifactorial nature of bone inheritance, the distinction between environmental and genetic factors is not straightforward.

To identify the sex of individuals with any degree of con fidence, it is necessary to know the parameters for sexual dimorphism in the specific population under investigation. When faced with an unknown population, as in the case of the Pompeian collection, it is essential to have a large sample to establish population norms.

Ideally, sexual attribution should be determined by an examination of the entire skeleton. This is impossible for the majority of the Pompeian material as a result of post-excavation disarticulation. Determination of sex for the different Pompeian bone samples was therefore based on both measurements and a standardized scoring system (see Table 6.1) from observations on samples of four different sets of bones, with emphasis on the pelvis (or innominate bone), followed by the humerus, the femur and the skull, including mandibles and teeth.

19

Various statistical techniques were employed to demonstrate whether there was a clear separation of measurements into two groups and whether there was skewing towards either robust or gracile measurements or observations. Based on the assumption that males are more robust, this would provide an indication of the proportion of ‘males’ to ‘females’ in the sample.

20

The pelvis is generally considered the most reliable skeletal indicator of sex as a result of its biological function.

21

The criteria that were used for sex determination were mostly visual. This enabled observations to be made quickly on the available sample.

Table 6.1

Scoring system for the determination of sex from observations on bones

Score Sex Attribution

1 hyperfemale

2 unequivocal female

3 more female than male

4 mid-range

5 more male than female

6 unequivocal male

7 hypermale

Notes: This scoring system was based on the five-point system devised by the ‘Workshop of European anthropologists’ in 1972 (Ferembach

et al

., 1980, 523). This scoring system is compatible with the 1994 standards (Buikstra

et al

. (eds), 1994, 19–21). I modified this system with the addition of two further scores to include equivocal cases for which a sexual attribution could be inferred.

bone in females to facilitate childbirth. The increase in length is greater at the symphyseal than the acetabular end of the bone.

22

As a result, the pubic region is the most useful portion of the pelvis for objective visual assessment of sex. Sex determination based on observation of this area is considered to be as reliable as metric analysis.

23

Unfortunately, this region, which is relatively fragile, tends not to survive well in many archaeological contexts and is not as well represented as other areas of the pelves in the Pompeian sample.

24

Some pelvic features are considered to be exclusive to females. It was initially assumed that these resulted from changes to the pelvis due to stress from childbirth, or parturition. The two most commonly claimed to result from parturition are pitting on the dorsal surface of the pubic symphysis and the presence of a pre-auricular sulcus or groove. It has been suggested that these changes to the bone reflect ligament damage caused during childbirth. The pubic ligaments tend to become relaxed prior to delivery, possibly as a result of the production of hormones, like relaxin, during pregnancy. This enables some movement and separation of the pelvic bones during childbirth. Too much strain can result in a lesion, which could leave a scar in the form of pitting on the bone.

25

This interpretation of these observed changes has been challenged. It has been argued that they do not necessarily result from childbirth-related injury, which is significant as it means that it is possible for similar changes to be observed on male pelves. For example, two forms of pre-auricular sulcus have been identified. The more ‘female’ form that has traditionally been associated with parity is thought to result from changes to the pelvic joint ligaments during pregnancy and childbirth and has been called a groove of pregnancy (GP). The other form is related to the degree of ligament development at the sacro-iliac joint and is described as a GL.

26

It should be noted that some inter-population variation has been observed for the pre-auricular sulcus. It does not tend to be so apparent on the pelves of certain populations, such as the Bantu, where sexual dimorphism is generally less marked than in Europeans.

27

Though it has been argued that there is some degree of correlation between the presence of dorsal pitting of the pubic symphysis and parity,

28

there are other factors which contribute to its occurrence, as such changes have also been observed on the pelves of men and nulliparous women. The latter group includes women who have either not had a pregnancy come to term or who have not had a natural delivery, as in the case of a Caesarean section.

29

Furthermore, these lesions tend to be obliterated with advancing age.

30

A study of human and non-human mammals revealed that there was not a strong correlation between the degree of change at the pubic symphysis and the preauricular area.

31

The uncertainty about the interpretation of these bony changes is a reflection of a major problem associated with skeletal identification. Many hypotheses about changes observed on bones are based on educated guesswork or observations on a limited number of cases. This is because access to skeletal material, of known individuals is limited by ethical considerations. Occasionally, it is possible to test hypotheses with well-documented archaeological material, as in the case of the large sample of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century skeletons with coffin plate and other documentary information that were excavated from the crypt of Christ Church, Spitalfields in London. Comparison between the skeletal evidence and biographic and genealogical data indicated that there was no correlation between childbearing and pitting in the areas where ligaments attach on the dorsal surface of the pubic symphysis and preauricular area. Instead, there was a significant correlation between pelvic size and pitting. It was concluded that these changes were more commonly observed on females than males because they tend to have a larger pelvic area.

32

In terms of the determination of sex for the Pompeian pelvic sample, the reasons for the appearance of these features is not as important as the fact that they tend to be correlated with females rather than males, though it is important to be mindful that presence of these features does not necessarily provide incontrovertible evidence for a female attribution.

Initially, both right and left pelvic bones were used for sexing as the results of the early stages of sorting suggested that there were a greater number of right than left bones. I decided that it would be useful to look at both sides to establish whether the sex ratios were the same. A quick visual assessment suggested the proportion of males to females was roughly equivalent on both sides. When the bones were finally sorted and broken pelves reconstructed, it was found that there was minimal difference between the numbers of innominates representing each side and I only recorded the left bones in detail.

Bones were originally de fined as adult only when epiphyseal fusion was complete (see Chapter 7). This definition, however, excluded certain bones where there was evidence of changes normally associated with female skeletons, such as a pre-auricular groove. The definition was cautiously altered to include bones where fusion was complete, except at the iliac crest and the tuberosity of the ischium. Fusion in these regions is often not completed until the third decade by which time the hormone changes to initiate sexual dimorphism have occurred and reproduction has been possible for some time.

33

It is notable that certain scholars

34

define innominates where fusion at the iliac crest has commenced as young adult rather than sub-adult. Sexual attributions based on innominate bones of individuals who had not yet attained complete maturity were noted separately.

Sex determination was based on a combination of ten observations and three measurements from a sample of 158 left adult and older adolescent innominate bones, mostly from the Sarno Baths.

35

This sample represents all the material that was available from the Pompeian collection.

Some of these features, such as the ventral arc, are known to be more useful discriminators than others. The range of features were chosen because they involved different parts of the bone, so that no matter how incomplete the specimen it would be possible to include it in the study. The more reliable indicators were employed as a baseline to enable population norms to be established for the pelves in the Pompeian sample.

As expected, the pelvis proved to be the most useful sex indicator of the samples of individual bones that were examined and should be used as a baseline for the interpretation of the other bones. It is notable, though not surprising, that the non-metric observations produced far better separation than the metric data. Since the morphology of the pelvis is based on biological function, the non-metric features were considered more reliable.

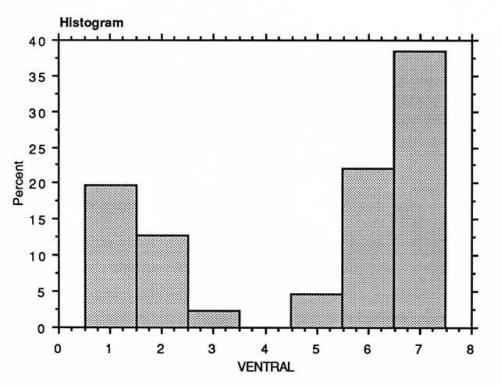

Both univariate and multivariate descriptive statistics produced similar results for the non-metric data (as typified by Figures. 6.1 and 6.2). Three main conclusions could be drawn with regard to the individual features. The first is that the best pelvic features for sex separation from the Pompeian material are the ventral arc, sub-pubic concavity and the sub-pubic angle, closely followed by the medial aspect of the ischio-pubic ramus and the obdurator foramen. The pre-auricular sulcus, sciatic notch and pubic tubercule are also good indicators but do not appear to separate the sample as well. The second is that the auricular area does not display any degree of bimodality (Figure 6.3) and, unlike the other features, is skewed towards the more female end of the range. It is clearly not a good sex separator but may perhaps be useful as a population descriptor. The third is that this research supported the assertion that dorsal pitting may not be specifically linked to parturition as it was also observed on pelves that were apparently male.

No matter how the data were treated in terms of statistical analysis, the pelvic observations, with the exception of the auricular area, consistently separated the sample into a higher proportion of males than females. This is at odds with the popular view that it was the women who were more likely to have become victims. The issue of sex determination from the pelvis, however, is complex and the results for individual non-pubic features do not necessarily reflect the actual ratio of males to females. Further consideration is required for the interpretation of the results.

It has been observed that female pelves tend to display more mid-range traits than males.

36

This certainly appeared to be the case for the Pompeian sample. Many of the pelves where the pubic region had not survived were rather androgynous in appearance and were difficult to classify. This phenomenon has been observed for other skeletal samples from central Southern Italy.

37

It is notable that Bisel considered the pelves in the Herculaneum skeletal sample to be highly dimorphic, though she probably had more complete bones in her sample (see below).

38

A number of pelves that were unequivocally female from examination of the os pubis, displayed either mid-range or male features, especially for the sciatic notch. In addition, it