Resurrecting Pompeii (24 page)

Read Resurrecting Pompeii Online

Authors: Estelle Lazer

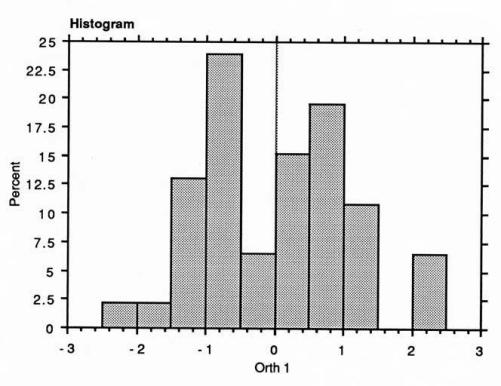

Figure 6.7

Frequency histogram of the factor scores of the first principal component identified from analysis of the observations from the mandible for the determination of sex

75

All the available canines that did not have teeth on either side or were able to be removed from their sockets from the Forum and Sarno Bath collections were measured. Teeth that were not isolated in the mouth were not measured in situ because it was found to be extremely difficult to get the callipers between teeth, especially those that had been worn flat. Measurements were only made on teeth where the crown was substantially intact.

Unfortunately, not many teeth met these criteria and the sample size was limited to 9 maxillary canines and 19 mandibular canines. This sample is not large enough to draw conclusions about sexual dimorphism in the Pompeian canine sample.

Nicolucci

76

stated that the sample of one hundred Pompeian skulls he examined in his 1882 study was composed of 55 males and 45 females. Unfortunately, he neglected to document the criteria he used to make this assessment. In addition to the stated reasons for this study, the metric data collected by Nicolucci for his 1882 study were examined to determine whether sex attribution was based solely on visual inspection of if any metric features were used. If the latter were found to be the case, the degree of concordance between his sex attributions and those determined from the metric data would also be considered. Six of Nicolucci’s key measurements appeared to be comparable with the current craniometric study. An additional nine measurements were considered.

77

In addition, Nicolucci calculated several cranial indices from the measurements he made,

78

though the one he considered most important, especially in terms of population studies was the cephalic index (Chapter 3). This is defined, as are all indices, in terms of a ratio of one measurement to another, expressed as a percentage of the larger one.

79

The other measurement that Nicolucci and other nineteenth-century scholars considered most important was cranial capacity (Chapter 3). There are a number of methods for taking this measurement and Nicolucci was not clear about the technique that he employed. The most common way of making this measurement is to fill the cranial cavity with mustard seed or small shot. When it is filled to the foramen magnum, the shot is emptied into a cubic centimetre measuring glass to be read.

80

Nicolucci’s results for cranial capacity were investigated to determine whether it was used as a basis for sex separation.

The metric data collected by Nicolucci also did not prove to be useful for the determination of sex,

81

which confirms the suggestion that this is a problem of the material and not the sample. It was not possible to establish the criteria that Nicolucci employed to separate his sample into males and females from the metric information. Perhaps the most interesting result from this exploration of Nicolucci’s data is revealed from an examination using cluster analysis. The fact that the data could not be forced into two groups suggests that the sample Nicolucci used was not comparable to that stored in the Forum Baths. The way the data split into specific groups perhaps implies that his sample was not random but was specially selected to include unusual specimens. It is notable that the alleged ‘negro’ skull he singled out formed a single cluster, implying that it really was significantly different from the other crania in his study.

The work of D ’Amore

et al

. on the skulls housed in the Forum baths produced slightly different results to those obtained in the current study.

82

They poured millet into the skulls and then ordered them by increasing cranial capacity. The cranial index was also calculated so that the two features could be compared. These measurements were chosen for sex attribution because, according to Krogman,

83

female cranial capacity is generally about 200 cc less than that of males, and females have a relatively higher cranial index because their skulls are more rounded. These two elements formed the basis of their classification. They also employed other, perhaps more traditional, indicators of dimorphism, such as the presence of frontal bosses, sharp orbital margins, smaller zygomas and palates, and smaller muscle attachments to identify females.

84

They classified 43 skulls as female and 80 as male. These figures were calculated as percentages, namely 35 per cent and 65 per cent respectively as compared to Nicolucci’s breakdown of 45 per cent females to 55 per cent males.

85

The choice of cranial capacity and cranial index as the major sex indicators for this study requires some comment. These features are not commonly employed for sex segregation in current studies of archaeological skeletal material and are generally not recommended as criteria for sexing in physical anthropological texts.

86

Further, it has been asserted that the most useful sex indicators on the skull are to be found in the region of the face rather than in the area that houses the brain.

87

While it can be claimed that there is a slight difference between the average cranial indices of men and women in a population, the veracity of the assumption that males have greater cranial capacity than females has been questioned. Though there is some correlation between brain and body size, it is not certain what the extent of overlap is for the range of cranial capacity. It has been suggested that in the past, undue emphasis was placed on size differences for the determination of sex from skulls.

88

It has been further asserted that data may have been manipulated in the past, either consciously or unconsciously, to confirm preconceived ideas, namely that greater cranial capacity in males was a reflection of male superiority.

89

D ’Amore

et al.

were concerned about the results they obtained. Though it was not explicitly stated, this was possibly because they expected their evidence to support the notion that women were more likely to have been victims than men. They conceded that they did not know how many people were able to escape from the eruption or who they were. In their opinion, only a modest number of bodies had been recovered from Pompeii because the majority of skeletons were either lost or not collected during the course of excavation. They argued, therefore, that the higher male to female sex ratio they calculated was not necessarily an accurate reflection of the population of Pompeian victims. A comparison of their findings with the sex ratios obtained by other scholars, including Nicolucci, who worked on ancient and recent Italian skeletal material, led them to conclude that the number of males always exceeded the number of females in Italian samples. They explained this phenomenon as the result of a high incidence of robust females in these samples.

90

It is possible that this explanation is correct, though the argument presented by D’Amore

et al.

to support this claim can be criticized. It is worth noting that the source for all their comparative data was compiled in 1904.

91

The methods for determining sex from skeletal material were improved considerably over the course of the twentieth century and it is possible that some of the sex attributions of these earlier works could be questioned. In addition, the documented tendency for a systematic bias towards male attributions from skeletal evidence

92

is unlikely to have been recognized, let alone corrected for, by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century anthropologists. Another possibility that D’Amore

et al.

do not appear to have considered is that the scholars whose work they cited may not have based their studies on random samples. Nicolucci certainly did not state the criteria he used for selecting his sample. It is probably reasonable to assume that he chose the more complete skulls available to him for measurement, along with those that he found interesting, such as the supposedly ‘negroid’ skull. The former may well have led to a bias towards the more robust skulls, which may explain the slightly higher number of males than females in his sample.

D ’Amore

et al

. also explored the possibility of misdiagnosis as another reason for the higher frequency of males in their sample. They expressed reservations about the accuracy of their sex attributions as a result of the problems of sex determination based solely from the skull. Nonetheless, they apparently made no effort to compare their results with post-cranial bones from the Pompeian collection. They merely cited examples from the skeletal literature, which reinforced the view that sexual diagnosis from the skull was difficult and potentially inaccurate. The problems of sex determination from skulls were considered to result from the lack of unequivocal sex specific characteristics and variation between populations.

93

D ’Amore

et al

. concluded that there was probably considerable overlap between the sexes for the features that they chose for sex separation in their sample of Pompeian skulls. This diminished their confidence in the results that they obtained. They suggested that the Pompeian skeletal series was more robust than they expected and that skulls which they classified as males may well have belonged to females.

94

Recent re-examination of the skulls, mandibles and pelves of essentially the same material used in my study confirmed the results reported in this chapter. Sex attribution based on the pelvis and mandible yielded a higher incidence of males to females, while examination of the skulls suggested more females than males.

95

Attribution of sex for the Herculaneum sample differed from that of Pompeii as individuals were represented by articulated, often complete, skeletons so there was no incentive to establish which bones were better indicators of dimorphism in the sample. As a result, comparisons of results for individual skeletal elements cannot easily be made between the two sites.

Of the 139 skeletons she studied, Bisel

96

determined 51 to be male and 49 to be female, the remaining 39 being juvenile and difficult to sex (see above). It is important to realize that these skeletons are included in all of the samples used by subsequent researchers.

Luigi Capasso established sex for 144 of the 162 skeletons available to him. He identified 83 as male and 61 as female. It is notable that he made sex attributions for juvenile skeletons, though he did acknowledge that there were problems with the technique he employed. He excluded a foetal skeleton that he sexed as female from these figures. He calculated the ratio of males : females as 1.38 : 1.

97

More recently, a sample of 215 Herculanean skeletons were studied by Petrone

et al

.

98

They did not attempt to establish sex from young juvenile bones but did make attributions for individuals aged from mid teen years. They also obtained slightly higher numbers of males than females, with 37.4 per cent of the total sample sexed as male and 31.8 per cent as female.

fi

nities

It is important to recognize that features associated with sex can be population specific. The determination of the sex of an individual is inextricably linked with their population affinities.

99

A number of features that were considered to be possible sex indicators, like the auricular area, are probably more useful as descriptors of the population. This is true for other features for different populations, such as the shape of the chin, brow ridges and septal apertures of the humerus.

100

The fact that there are not many diagnostic features for the separation of the Pompeians into male and female categories can also be interpreted as a population feature.

Skulls, in particular, have long held a fascination for scholars (see Chapter 3) and have often been the primary bone used for analysis. This study indicates that, at least for the Pompeian sample, they are of limited value. In addition, the inability of the metric data to provide information on intrapopulation data in the form of sex separation does not augur well for their value as population discriminators for the Pompeian victims.

The assumption that the sample of Pompeian victims was skewed towards females is not supported by the skeletal evidence, which suggests that, if anything, the sample has more of a male bias. No explanation can be offered for such a bias, especially because it is difficult to interpret whether or not it is significant owing to the problem of overlap.

It is notable that different bones provided different sex ratios. The pelvic non-metric observations yielded a considerably higher incidence of males in the sample, whilst the humeral and skull measurements along with the mandible observations, suggested almost equal separation with a slightly higher frequency of males. In contrast, the results from the femur measurements implied a greater number of more gracile, presumably female, individuals in the sample. Similarly, the pelvic measurements and the non-metric skull observations suggest that the sample was composed of more females than males.

Interpretation of these results is dependent on the establishment of which bones and traits are the most useful indicators of sex for the Pompeian sample. The results from the femur can be questioned on the basis of sample bias as a number of the bones were removed from the Pompeian stores for secondary usage as hinges (see Chapter 5). From the results, it appears that the bones that are most useful features for sex separation for this sample are the non-metric pelvic traits, followed by the non-metric mandible traits and the humerus measurements.

The association between sex and population is well documented with sexual dimorphism varying between populations. It appears as if the Pompeian sample shows a tendency towards androgyny for certain features, especially in the pelvis and skull. This study indicates that the skull, and the craniometric data in particular, is not very useful as a sex indicator for the Pompeian sample and, by implication, cranial measurements are of limited value for the determination of population affinities for this sample. This is because they did not indicate any real separation into well-defined groups. This could be explained if the sample were heterogeneous, though other evidence that has been collected does not support this view. The results of this research suggest that these cranial measurements are not a good indicator for either sex or population affinities for the Pompeian sample.