Red Capitalism (11 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

What is the nature and value of these assets? The various PBOC securities, as well as the 1998 MOF bond, are clear obligations of the sovereign. But what value should be assigned to the AMC bonds or, for that matter, the MOF “receivable?” Obviously a receivable due from the MOF is similar to a government bond . . . on the surface. The bond, however, has been approved by the State Council and the NPC as part of the national budget. Such government bonds will be repaid either by state tax revenues or further bond issues. Who has approved the issuance of that IOU? How will it be repaid? These are important questions, given each bank’s massive credit exposure to these securities. For example, the total of these restructuring assets is nearly twice ICBC’s total capital, with the AMC bonds alone representing 53 percent. The sections below seek to understand how these obligations arose and what they practically represent in order to determine their value and structural implications for the banking system as a whole.

THE PEOPLE’S BANK OF CHINA RESTRUCTURING MODEL

From the viewpoint of strengthening the banks, the original PBOC model was the most effective, providing additional capital to the banks through a combination of more new money and better valuations for problem loans. In the first step in 1998, bank capital was topped up to minimum levels required by international standards. This was followed by the transfer of US$170 billion of bank NPL portfolios to the AMCs at 100 cents on the dollar. These “bad banks” paid cash, using a combination of PBOC loans and AMC bonds, for the bad-loan portfolios. However, these injections of cash came just at a time when inflation was looming. Consequently, the PBOC sterilized the incremental cash on bank balance sheets by forced purchases of PBOC bills, which could not be used in any further financing transactions. This is the source of the PBOC securities listed in

Table 3.1

. In 2003, additional bad loans remaining on the balance sheets of CCB and BOC were completely written off up to the amount of the total capital of each bank, a total of RMB92 billion (US$12 billion). Bank capital was then replenished from the country’s foreign-exchange reserves and with investments from foreign strategic investors. CCB and BOC were restructured in this way and completed successful IPOs in 2005 and 2006.

The partial recapitalization of the Big 4 banks, 1998

On the collapse of GITIC and amid rumors of bank insolvency, in 1998 Zhu Rongji ordered a rapid recapitalization of the Big 4 banks to at least minimum international standards, which were the only standards available to China. A mountain of bad loans had been created in the late 1980s and early 1990s and ignored for 10 years. This was the typical approach of the bureaucracy toward intractable problems. By 1998, however, it had become obvious to the government that such methods increased systemic risk. At that time, China’s banks had never been audited to strict professional standards or, for that matter, to

any

professional standard. As with GITIC, no one could say with confidence how big the problem might be. Given Wang Qishan’s experience in having to answer an angry Premier’s questions about GITIC’s black hole, one can imagine the pressure people at the MOF must have felt as they sought to come up with a figure that would satisfy Premier Zhu.

There was, of course, no time for a real audit, but someone was clever enough to come up with a number purportedly sufficient to raise bank capital adequacy to eight percent of total assets, in line with the Basel Agreement on international banking standards. This figure turned out to be RMB270 billion (US$35 billion). For China, in 1998, this was a huge sum of money, equivalent to nearly 100 percent of total government bond issuance for the year, 25 percent of foreign reserves and about four percent of GDP. To do this, the MOF nationalized savings deposits largely belonging to the Chinese people (see

Table 3.2

).

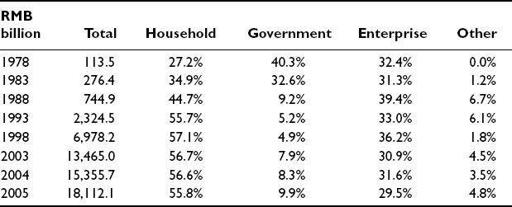

TABLE 3.2

Composition of Big 4 bank deposits, 1978–2005

Source: China Financial Statistics 1949–2005

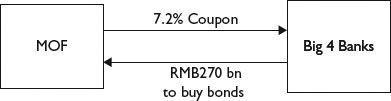

In the first step, the PBOC reduced by fiat the deposit-reserve ratio imposed on the banks, from 13 percent to eight percent. This move freed up RMB270 billion in deposit reserves which were then used on behalf of each bank to acquire a Special Purpose Treasury Bond of the same value issued by the MOF (see

Figure 3.1

).

2

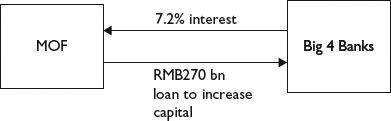

In the second step, the MOF took the bond proceeds and

lent them

to the banks as capital (see

Figure 3.2

). This washing of RMB270 billion through the MOF in effect made the banks’ depositors—both consumer and corporate—

de facto

shareholders, but without their knowledge or attribution of rights.

FIGURE 3.1

Step 1 in recapitalization of the Big 4 Banks, 1998

FIGURE 3.2

Step 2 in recapitalization of the Big 4 Banks, 1998

As part of the CCB and BOC restructurings in 2003, these nominally MOF funds totaling RMB93 billion for the two banks were transferred entirely to bad-debt reserves and then used to write off similar amounts of bad loans.

3

This left the Ministry of Finance responsible for repayment. For the banks this was a good deal, as the MOF was now obligated not just to “repay” what was originally the banks’ money anyway, but to use its own funds to do so. It is no wonder, therefore, that the bond maturities were extended to 2028, just as it is no wonder that the MOF did not support the PBOC approach to bank restructuring. How could it when, without the approval of State Council and National People’s Congress, it had no access to such massive amounts of money?

Bad banks and good banks, 1999

Having shored up the banks by such accounting legerdemain, work began on preparing them for an eventual IPO. Zhou Xiaochuan proposed the international “good bank/bad bank” strategy that had been used successfully in the Scandinavian countries and the US. This involved the establishment of a “bad bank” to hold the problem assets spun off by what then becomes a “good bank.” Zhou proposed the creation of one “bad” bank, called an “asset-management company,” for each of the four state-owned banks. It was a critical part of the plan that, after the NPL portfolios had been worked out, the AMCs would be closed and their net losses crystallized and written off, a process that was expected to take 10 years. In 1999, the State Council approved the plan and the four AMCs were established.

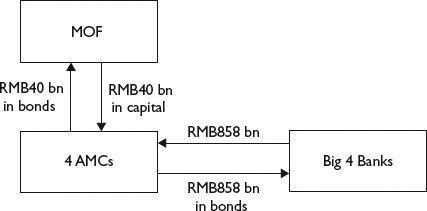

The MOF capitalized each AMC by purchasing Special AMC Bonds totaling RMB40 billion or roughly US$1 billion each (see

Figure 3.3

). In line with the plan to close the companies, these bonds had a maturity of 10 years. But RMB40 billion was hardly enough to acquire bank NPL portfolios. More funds were needed and where else to get them but from the banks themselves? The AMCs, therefore, issued 10-year bonds to their respective banks in the amount of RMB858 billion (US$105 billion).

FIGURE 3.3

AMC capitalization by the MOF and each bank, 1999

These bonds represent the major flaw in the PBOC plan. The significance of the bonds is that the banks remain heavily exposed to their old problem loans even after they had been nominally “removed” from their balance sheets. The banks had simply exchanged one set of demonstrably non-performing assets for another of highly questionable value. The scale of this exposure was also huge in comparison to bank capital (see

Table 3.1

). Given the size of the bank recapitalization problem in comparison to China’s financial capacity at the time, the government had little choice but to rely on the banks. But this approach was not in line with the international model and did not solve the problem.

In the Scandinavian and US experience, the national treasury had not only capitalized the bad banks, but it had also provided financing to them so that the resulting “good” banks had no remaining exposure to their old bad loans. They had become the problem of the national treasury and ultimately their cost would be paid for from taxes. In China, as long as the government’s reliance on the banks to fund the AMCs remained “inside the system,” it may not have mattered. A supportive bank regulator could rule that AMC bonds were those of semi-sovereign entities and the question as to their creditworthiness could be avoided. But once these banks became listed on international markets and were subject to scrutiny by other regulators and investors, international auditors would inevitably question the valuation of these bonds. The AMCs were thinly capitalized at about US$5 billion. The bonds they had issued totaled US$105 billion and the assets they funded had, by definition, little value. What if the AMCs could not achieve sufficient recoveries on the NPL portfolios to repay the bonds due in 2009?

NPL portfolio acquisition by the AMCs, 2000

The first acquisition of bad-loan portfolios by the new AMCs began and was completed in 2000. A total of RMB1.4 trillion (US$170 billion) in NPLs was transferred

at full face value,

dollar-for-dollar, from the banks to the AMCs. This was funded by the bond issues and a further RMB634 billion (US$75 billion) in credit extended by the PBOC (see

Figure 3.4

). The obvious question that arises is: if these loans were really worth full face value, why were they spun off in the first place? There are a number of possible reasons for this. One is that any write-down by the banks in 2000 would have wiped out all capital injected by the MOF in 1998 and there was, as yet, no consensus on where new capital would come from. Given the amounts involved, there were, after all, limited choices. This is surely part of the answer. Another part is that this transfer was equivalent to an indirect injection of capital since the replacement of bad loans with cash would free up loan-loss reserves (if any). Going forward, it would improve bank profitability and capital by reducing the need for loan-loss provisioning.