Red Capitalism (10 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

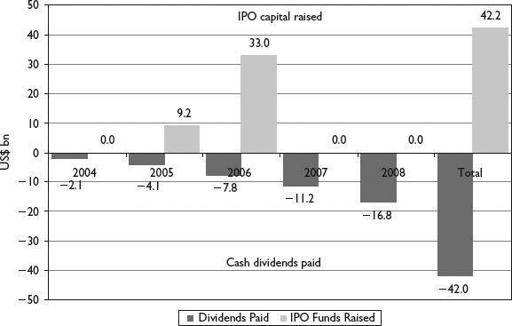

FIGURE 2.7

Bank IPOs pre-fund cash dividends paid, 2004–2008

Source: Wind Information for IPO amounts; Statement of cash flows, bank annual reports

Investors, as opposed to speculators, put their money in the stocks of companies, including banks, in the expectation that management will create value. But in these three banks, this is not what is happening because the capital did not stay in the banks. Yes, the minority international investors acquired stocks that vary in value in line with market movements. This gives the impression of value creation on their portfolios, but these movements are, in fact, due more to speculation on market movements driven by any number of factors including, for example, overall Chinese economic performance. This should not be confused with value investing: the banks themselves are not putting the money to work to make the investor a capital return. For this reason alone, the market-capitalization rankings are misleading.

As for the Chinese state, which holds the overwhelming majority stake in these banks, such payouts mean the banks will require ongoing capital-market funding after their IPOs. This, in turn, means the government must, in effect, re-contribute the dividends received as a new equity injection just to prevent having its holdings diluted. There can be only one IPO for each bank and one infusion of purely third-party capital.

10

What is the purpose of running a bank that pays dividends to a state that must then turn around and put the same money back again? Why sustain dividend payout ratios at 50 percent or higher? This begins to look very much like some sort of Ponzi scheme, but to whose benefit?

Of course, it is more than that: China’s banks are the country’s financial system. But, as the analyst said, they operate a business model that requires large chunks of new capital at regular intervals. With high dividend payouts and rapid asset growth, consideration must inevitably be given to the issue of problem loans. How can banks as large as China’s grow their balance sheets at a rate of 40 percent a year, as BOC did in 2009, without considering this? Even in normal years, the Big 4 banks increase their assets through lending at nearly 20 percent per annum. Throughout 2009, as the banks lent out huge amounts of money, their senior management emphasized over and again that lending standards were being maintained. How was it, then, that the chief risk officer of a major second-tier bank could exclaim even before 2009: “I just don’t understand how these banks can maintain such low bad-loan ratios when I can’t?” His astonishment suggests there may be less-than-stringent management of loan standards by the banks’ credit departments. This is undoubtedly true.

The most important fact behind the quality of these balance sheets, however, goes beyond common accounting manipulations or even making bad loans. These things are inevitable almost anywhere. It goes back to the financial arrangements made by the Party when weak bank balance sheets were restructured over the years from 1998 to 2007. A close look at how these banks were originally restructured highlights the political compromises made during this decade-long process. These compromises have been papered over by time and weak memories on all sides: it is highly likely, for example, that China’s national leaders believe that their banks are world-beaters. In the past, sweeping history under the carpet might have been enough; people would have forgotten. Today, it is far from enough, even for those operating inside the system. The key difference with the past is that the quest to modernize China’s banks was made possible by raising new capital from international strategic investors and from subsequent IPOs on international markets. China’s major banks are now an important part of international capital markets and subject to greater scrutiny and higher performance standards . . . just as Zhu Rongji had planned.

ENDNOTES

1

See Demirguc-Kuntand Levine 2004: 28.

2

“Inside the world of a red capitalist: Huang Yantian’s financial powerhouse is helping to remake China,”

BusinessWeek

, May 1994.

3

Li, Liming and Cao, Renxiong,

1979–2006 Zhongguo jinrong dabiang

e(

1979–2006 The Great Reform of China’s banking system

). Shanghai: Shiji chuban jituan: 474.

4

Walter and Howie 2006: 181ff.

5

Ibid., Chapter 9.

6

Curry and Shibut 2000.

7

21st Century Business Herald 21, April 13, 2010: 10.

8

Yang excludes ABC, which listed its shares later in 2010.

9

“ICBC says China’s banks need $70 billion capital,”

Bloomberg News

, April 13, 2010.

10

The first round of fund raising via an IPO involves the sale of new shares. This brings new capital into the bank and dilutes the original shareholdings. Thereafter, if the bank sells shares again, the Chinese state must also inject money or have its stake diluted.

CHAPTER 3

The Fragile Fortress

“Growing big is the best way for Chinese banks to make more money . . . This model of growth, however, neither assures the long-term sustainable development of the banking sector nor satisfies the need of a balanced economic and social structure. Things are very complicated; so will be the solutions.”

Xiao Gang, Chairman, Bank of China

August 25, 2010

1

When the Asian Financial Crisis threatened the stability of China’s financial institutions in 1997, Zhu Rongji sponsored a group of reformers surrounding Zhou Xiaochuan, then chairman of the CCB, to come up with a plan. The immediate threat to confidence in the banks was addressed by the MOF injecting new capital into the banks in 1998. As a second step, Zhou’s group proposed a “good bank/bad bank” approach to strengthen the balance sheets of the Big 4 banks. Modeled after the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) in the US, asset-management companies (AMCs) would be established for each of the banks. The AMCs would become the “bad” banks holding the non-performing loans (NPLs) of the resulting “good” banks. These bad banks would be financed by the government and be responsible for recovering whatever value possible from NPLs. The State Council approved the proposal and in 1999 the AMCs were set up. (See appendix for organizational charts of China’s resulting financial system).

In 2000, huge problem-loan portfolios were transferred to the AMCs, freeing the banks of massive burdens and enabling them to attract such blue-chip strategic investors as Bank of America and Goldman Sachs. These international investors were brought in less for their money than for the expertise that the government hoped could be transferred to its banks. But, in a rising crescendo of criticism, conservative and nationalist critics claimed a “sell-out” to foreign interests. Even so, in 2005, CCB enjoyed a wildly successful IPO in Hong Kong, raising billions of dollars in new capital. With this IPO, Zhu and Zhou’s efforts achieved a very significant success where, several years before, few had believed such a thing possible for a Chinese bank. Unfortunately, the very success of bank reform fed the fire of conservative criticism which was now amplified by the PBOC’s institutional rivals, who wanted to cut Zhou and the central bank down to size. Among these rivals were the NDRC, the CSRC, the CBRC and, most particularly, the MOF. The impact of this concerted criticism affected the financial restructuring process, beginning with ICBC and continuing through to ABC. It also had the effect of ending Zhou’s integrated approach to capital-market and regulatory reform.

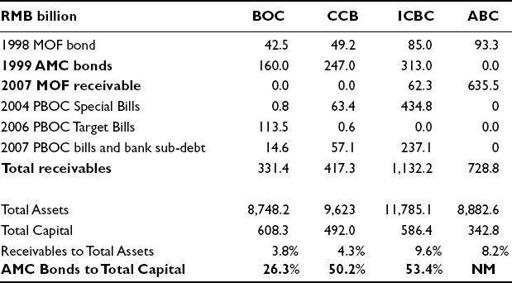

The practical consequence for the bank reform was the creation of two different approaches to balance-sheet restructuring. Of course, the original plan for all four banks was superficially retained, even after the MOF assumed the leading position in the reform of ICBC and ABC in 2005. No better ideas had been generated as a result of all the criticism, so each of the four banks raised capital through IPOs. But the paths to restructuring differed, as did the manner in which NPL portfolios were disposed of. The major financial liabilities remaining on bank balance sheets arising from the two different approaches are shown in

Table 3.1

. Information in this table is derived from the banks’ financial statements under the footnote “Debt securities classified as receivables.” The table illustrates the continuing and material exposure of China’s major banks to securities created as a result of their restructuring a decade ago. The simple message of these “receivables” is that the old bad debt has not gone away; it is still on bank balance sheets but has been reclassified, in part, as “receivables” that may never be received.

TABLE 3.1

Restructuring “receivables” on bank balance sheets

Source: Bank audited financial statements, December 31, 2009