Red Capitalism (14 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

The resulting analysis suggests that the four AMCs lost their RMB40 billion in capital entirely, with estimated write-offs of RMB1.5 trillion (US$176 billion) yet to be taken. This represents a loss rate of around 50 percent. While the profit or loss of the AMCs is only a rough guess, the amount of the write-offs is a more accurate figure and, what is more, they remain on the balance sheets of these four non-public, non-transparent enterprises.

The reason write-downs have not been taken is straightforward. A full or even partial write-off would lead to the outright bankruptcies of the AMCs, confronting the government with a difficult choice: either the banks would suffer significant losses on the AMC bonds or the MOF would have to bear the burden and explain to the NPC. At the outset of the reform process and the creation of the bad banks, their closure and full write-offs, including MOF payment on their bonds, had been part of the plan and explained as such.

Over the years, however, the plan had been changed and the MOF had assumed responsibility as a result of its bureaucratic victory over the PBOC. Now, in 2009, the banks seemed to be performing like world-beaters and the AMCs were noisily talking up their panoply of financial licenses; everyone had deliberately forgotten the history. Why should the MOF rock the boat when it is far easier to defer any decision until a more convenient time?

This is just what happened. In 2009, as their bonds came due, the AMCs were not closed down and their bonds were not repaid. Instead, the State Council approved the extension of bond tenors for a further 10 years. To support their full valuation on bank balance sheets, the MOF provided international auditors written support for the payment of interest and principal. Each bank’s annual financial report contains language such as the following from CCB’s 2008 report: “According to a notice issued by the MOF, starting from January 1, 2005, the MOF will provide financial support if Cinda is unable to repay the interest in full. The MOF will also provide support for the repayment of bond principal, if necessary.” Of course, a “notice” is not quite a guarantee; the MOF would never commit itself in writing to that. It does mean that it will in some way support the repayment of these obligations, unless at some point it is unwilling or unable to do so. Guarantees always come due at inconvenient times, as their extension in 2009 indicates. Until then, CCB, BOC and ICBC continue to carry these bonds at full value. As

Table 3.1

shows, a default, or even a write-down of their value, would significantly impair the capital base of these banks and inevitably require yet another recapitalization exercise.

THE “PERPETUAL PUT” OPTION TO THE PBOC

This review of how the asset-management companies were used to resolve the problem-loan crisis in the banks highlights perhaps the most important part of the banking system: the perpetual “put” the PBOC has extended to the AMCs. In fact, this “put” extends beyond the AMCs to the entire financial system and weakens any reform effort that might be undertaken. It is the Party’s shield against financial catastrophes. In the name of “financial stability” the Party has required the PBOC to underwrite all financial cleanups, of which there have been many—from the trust-company fiascos of the 1990s, the securities bankruptcies of 2004–05 to the banks—at a publicly estimated (and probably underestimated) cost of over US$300 billion as of year-end 2005 (see

Table 3.6

).

7

With this option available to them, bank management need care little about loan valuations, credit and risk controls. They can simply outsource lending mistakes to the AMCs, perhaps on a so-called negotiated “commercial” basis, and the AMCs will be almost automatically funded by the PBOC.

TABLE 3.6

Estimated historical cost to the PBOC of “Financial Stability” to FY2005

| Time Period | Amount (RMB billion) | Use |

| 1997–2005 | 159.9 | Re-lending to closed trust cos., urban bank co-ops, and rural agricultural co-ops to repay individual and external debt |

| 1998 | 604.1 | Re-lending to the 4 AMCs for first-round acquisition of bank NPLs |

| From 2002 | 30.0 | Re-lending to 11 bankrupt securities companies to repay individual debt |

| 2003 and 2005 | 490.2 | Huijin recapitalizes BOC, CCB, and ICBC |

| 2004–2005 | 1,223.6 | Re-lending to 4 AMCs for second-round acquisition of bank NPLs |

| 2005 | 60.0 | Additional lending to bankrupt securities companies to repay individual debt |

| 2005 | 10.0 | Re-lending to Investor Protection Fund |

| Total | 2,577.8 | |

| US$ billion | 315.5 |

Source: The Economic Observer , November 14, 2005: 3; PBOC Financial Stability Report 2006: 4; Caijing

, November 14, 2005: 3; PBOC Financial Stability Report 2006: 4; Caijing , July 25, 2005: 67

, July 25, 2005: 67

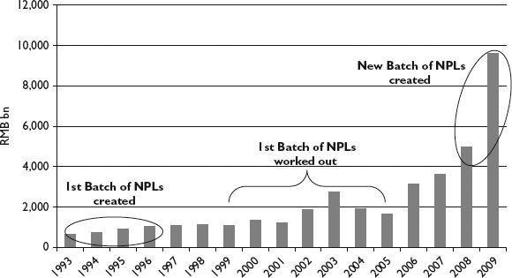

The new Great Leap Forward Economy

Added to the still unresolved loans of the 1990s, the US$1.4 trillion lending binge of 2009 will inevitably lead to correspondingly large loan losses in the near future (see

Figure 3.7

). The borrowers and projects are the same as in the previous cycle—infrastructure projects, SOEs and local-government “financing platforms, which will be discussed further in Chapter 5. But this time, their scale of borrowing is much, much larger; the press has even taken to referring to this as “Great Leap Forward Lending,” harking back to Mao Zedong’s ill-considered Great Leap Forward of 1958–1961. In early 2010, the regulators and Party spokesmen have taken the line that such investments will pay off over time. This is being echoed by brigades of analysts the world over, but the implication is well-understood by the Party itself. As one official put it simply: “In the near term, there will be no cash flow.” In other words, a large portion of these loans, over 30 percent of which reportedly went to localities, are already in default. Can the demise of the AMCs as originally called for in 1999 really be expected when their use has proven to be so great? To what extent can the Ministry of Finance continue to issue its IOUs?

FIGURE 3.7

Incremental bank lending, 1993–2009

Source: PBOC, Financial Stability Reports, various

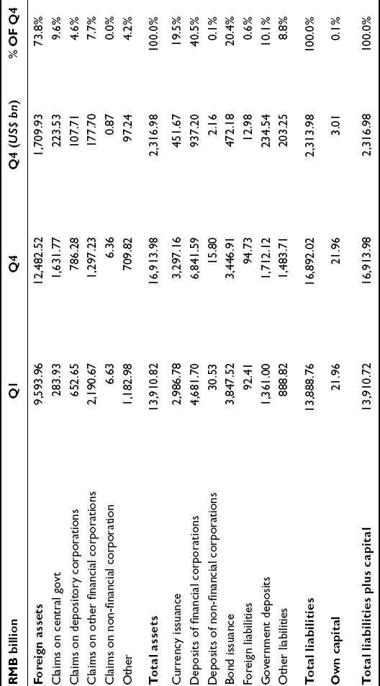

Against this background, it is not surprising that questions have been raised about the PBOC’s ability to continue to write the check for the Party’s profligate management of the country’s finances. It is interesting that the PBOC made public its own balance sheet for 2007 and that discussion around a recapitalization was rumored at about the same time (see

Table 3.7

).

8

This may well explain, at least in part, the use of IOUs written by the MOF for the Agricultural Bank of China restructuring. The 2007 figures show that the central bank is leveraged at nearly 800 times its own capital.

TABLE 3.7

PBOC balance sheet, 2007

Source: PBOC, Financial Stability Report, 2008

It should not be surprising, therefore, that in August 2005, the PBOC created its own asset-management company designed to take “problems left over from history” off its own balance sheet. Huida Asset Management Company (Huida) was described in its brief appearances in the press as the fifth AMC and its operations since 2005 have remained mysterious since it did not sell its distressed-debt portfolios to outside investors. Huida was meant to operate as the twin to Huijin; Huijin made investments in the financial system that created problem assets while Huida was to collect on unpaid loans associated with such assets when and if they were taken on by the PBOC as part of its operations to maintain financial stability.

Huida, like Huijin, was a creation of the Financial Stability Bureau of the PBOC and all its senior management were staff in the Bureau, just as others were senior staff of Huijin.

9

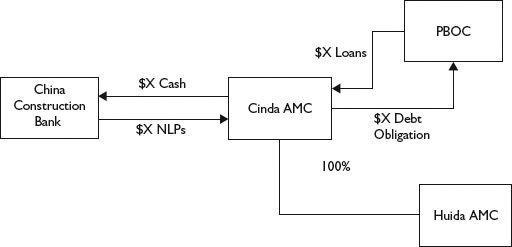

But unlike Huijin’s bank investments, the PBOC wanted to remove problem assets from its own balance sheet. Consequently, the actual equity investor in Huida had to be a third party and, given its close connections with the PBOC, Cinda AMC was the obvious choice (see

Figure 3.8

).

FIGURE 3.8

The establishment of Huida AMC, 2005