Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (35 page)

Read Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East Online

Authors: David Stahel

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Modern, #20th Century, #World War II

On

the Soviet side the invasion induced nothing short of utter chaos which was most strikingly evident in the Western Military District opposite Army Group Centre.

15

Here the Soviet command structure was rendered largely redundant almost from the very beginning owing to a near total loss of communication at most levels of the chain of command. The complete disarray prevented coherent knowledge of the current situation from being gathered and consequently the development and execution of a co-ordinated Soviet response. Racked by internal confusion and the growing external pressure, the Western Military District's hasty slide towards disintegration was worsened by the Soviet High Command's erroneous adherence to pre-war plans, which called for immediate counter-attacks.

16

Unable to properly prepare or direct these attempts, they inevitably resulted in piecemeal attacks of little effect, but carried out at great cost to Soviet forces.

17

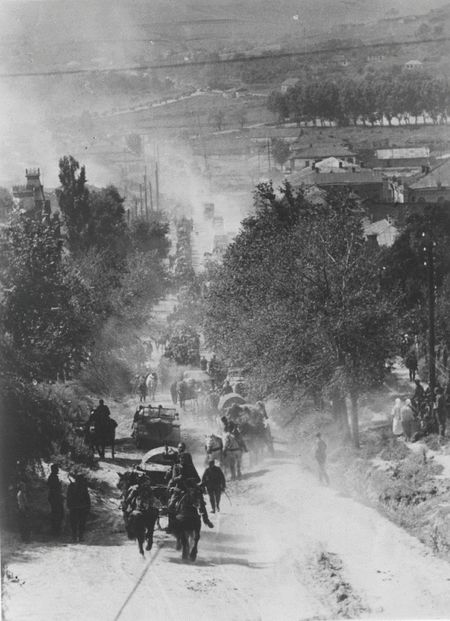

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.1

The advancing German columns stirred up great clouds of dust, which soon infiltrated motors and caused severe irritation to horses and men.

On the second day of the offensive

Halder proclaimed operations at Army Group Centre to be proceeding ‘according to plan’ and talked of soon achieving ‘full operational freedom’ behind the shattered Soviet front.

18

On the same day, in response to

Paulus's assessment that the campaign would be of short duration,

Brauchitsch is said to have responded: ‘

Yes, Paulus

, you may be right, we shall probably need six to eight weeks for finishing

Russia.’

19

In contrast to his superiors Field Marshal

Bock's impression was a far more guarded one. His diary noted the stubborn resistance of the Soviet defenders prompted by political commissars who

were spurring their men to ‘maximum resistance’. He also recorded with a note of unease that the state of the roads was ‘indescribable’.

20

More worrying still, Bock was again starting to question the wisdom behind the operational plan, foreseeing the closure of a pocket at

Minsk as unlikely to achieve a decisive success. In Bock's view a direct drive by Hoth's panzer group in the direction of

Vitebsk-Polotsk would save time and prevent an organised Soviet force being assembled on the eastern banks of the great rivers. As Bock noted:

I fear the enemy will already have withdrawn strong elements from there [Minsk]. By turning the panzer group towards Minsk time will be lost, which the enemy can use to establish a new defence behind the

Dvina and

Dnepr.

21

After failing to convince Halder of his concerns, Bock attempted to persuade Brauchitsch only to receive a similar rejection. It was only the second day of the campaign and far from winning operational freedom behind the Soviet line, as Halder believed, Bock was already convinced that the deepest possible penetration was required to cut off the great mass of the Red Army and forestall the building of a new defensive line. Bock's anxiety would have been further heightened by a report from

4th Army communicated to OKH which, according to Halder, characterised the overall picture: ‘The enemy in the Belostok salient is not fighting for his life, rather to gain

time.’

22

In the meantime,

XXXXVII Panzer Corps was already reporting fuel shortages among its furthermost elements, while the roads leading to and from the

Bug crossings had deteriorated so much that it was difficult moving the great volume of traffic – a considerable complication when a large portion of the wheeled transport, containing vital fuel supply, was still queued up on the western bank of the river.

23

On the other flank, Hoth's wheeled columns had penetrated deeper, but were experiencing even greater problems maintaining contact with the armoured spearheads. On 24 June the panzer group's war diary complained that road conditions restricted movement to a single-file column, reducing speeds to the slowest moving vehicle and stretching out even further when the heavily loaded tracks became bogged. Furthermore, the diary observed: ‘All routes marked as roads turned out to be unsealed, un-maintained sand tracks. The difficulties are placing great demands on

the divisions.’

24

The situation was not helped by the panzer group's high proportion of French vehicles which were already revealing their fragility. The

20th Panzer Division reported that their vulnerability to overland conditions was already ‘very noticeable’. ‘The trucks can only manage a few metres alone before needing to be dug out and then pulled and pushed.’

25

Furthermore, their fuel consumption was ‘many times more than normal’, inhibiting the supplies that could be brought

forward.

26

Even Halder noted that lubricant and fuel utilisation was ‘very high’.

27

The mass of infantry divisions were also finding movement exceedingly difficult owing to the severe traffic congestion. Doctor

Hermann Türk noted in his diary on 24 June: ‘The march goes dreadfully slowly. Always only a few metres forwards…Overtaking is impossible…We should be another 150 kilometres further ahead…Time is vital, but what can we do given the fully clogged roads?’

28

Although large-scale Soviet counter-attacks were essentially ineffectual, and suffered in most cases appalling losses, at the very least they forced the panzer or infantry corps to halt their advance in order to meet and repel the desperate onslaughts. As

Bock noted for 24 June:

The Russians are defending themselves desperately; heavy counterattacks near

Grodno against the

VIII and

XX Army Corps; Panzer Group Guderian is also being held up near

Slonim by enemy counterattacks.

29

Whatever delays and casualties these early Soviet counter-attacks caused German forces, because they involved such horrendous Soviet losses their significance in much of the literature has largely been to prove the one-sided nature of the conflict, favouring the notion of an unremitting German blitzkrieg. Yet what this focus tends to obscure is that, from the earliest stages of the war, German losses were far from inconsiderable. Typically, German casualties were not the result of major battles in conventional engagements with the Red Army. Rather it was the very dissolution of organised Soviet fighting formations, caused by the utter breakdown in command and control, which led to countless smaller actions that were of no prominence in their own right, but collectively extracted a significant toll on the invading forces. On only the third day of the conflict

Halder noted that casualties were ‘bearable’ but then added: ‘Remarkably

high losses among

officers’.

30

Soviet

tactics in this period were crude, but effective. Characteristic engagements were initiated by small groups of Soviet soldiers, often in selected positions, against unsuspecting German forces. This provided a far more even playing-field against the German superiority in heavy weapons, mobility and airpower. The

dense

Belorussian forests and high summer cornfields provided excellent cover for these forces, allowing them to prepare ambushes close to the roads on which the Germans depended. With ever longer German columns stretching out across the countryside, an inevitable gap opened between the panzer spearheads and the trudging infantry, leaving the vital, but poorly armed supply columns exposed to attack, even from small bands of men without heavy weapons. In essence it gave rise to an immediate and effective form of guerrilla resistance, with the advantage that it was carried out by soldiers with military-issue equipment instead of by peasants. Already on 24 June, the

3rd Panzer Group reported that the forests were full of fugitive Soviet soldiers who were ‘attacking from the flank and rear’ causing unrest and ‘slowing the advance’. The request was therefore made that reserves from Colonel-General Adolf

Strauss's

9th Army be dispatched to ‘clean out the woods’.

31

The enormous area in question made this an impossible task, especially for the exceedingly limited German reserves. Indeed at no point in the war did German security forces succeed in eliminating partisan resistance in Belorussia – on the contrary, these forces grew in number and effectiveness. The same pattern of attacks also dogged

2nd Panzer Group's rear area from the very beginning of the war. A former officer in the

3rd Panzer Division reported:

During the first two days of combat, unarmoured troops and rear echelons suffered considerable losses inflicted by hostile enemy troops cut off from their main bodies. They hid beside the march routes, opened fire by surprise, and could only be defeated in intense hand-to-hand combat. German troops had not previously experienced this type of war.

32

General Heinrici wrote on only the second day of the war: ‘All over the large forests, in countless homesteads, sit lost soldiers who often enough shoot at us from behind. The Russian fights war in devious ways.’

33

Having failed to win over

Halder or

Brauchitsch to his idea of a deep encirclement on the Dvina and Dnepr Rivers,

Bock tried again on the following day (24 June), but to no avail.

34

In part, as a result of Bock's strenuous urgings and perhaps with a view to the divisive disputes which arose in May 1940 over the speed of the advance through

Belgium, Halder and Brauchitsch were already conceiving a radical new reorganisation of

Army Group Centre's command structure. Halder was determined that the OKH would maintain a tight grip on the motorised and panzer divisions, setting the pace and direction of operations without having its hand forced by independently minded field commanders operating on their own initiative. Halder had in mind that the two panzer groups should no longer be directly answerable to Bock, whom he suspected of being too sympathetic to a headlong rush eastwards favoured by

Hoth and

Guderian. Instead Halder favoured uniting the two panzer groups under the more conservative direction of Field Marshal Günther von

Kluge, currently employed in command of the

4th Army. The new combined panzer group would be known as ‘Fourth Panzer Army’, with the 4th Army now under the command of Colonel-General Maximilian Freiherr von

Weichs and re-designated

2nd Army. The 2nd Army, in collusion with the

9th Army, would then have the task of completing the encirclement of the

Belostok salient, relieving the panzer and motorised divisions for further operations.

35

Bock's fervent opposition to sealing off the Belostok–Minsk pocket was keenly matched by Hoth, who likewise considered the operation an unconscionable delay and wanted to exploit the initial penetration immediately and push on into the easterly

Vitebsk–Orsha region to secure the land-bridge between the

Dvina and

Dnepr Rivers. Aware of Bock's stalled efforts to influence matters at OKH, Hoth dispatched Lieutenant-Colonel Hünersdorff, the OKH liaison officer attached to 3rd Panzer Group, to present the panzer commander's case personally. It must have dawned on Halder that the very same issue had already arisen in March 1941, long before the campaign was underway, and resolved at that time to the satisfaction of the OKH, with the first operational movement closing in the region of

Minsk. In his memoirs, Hoth makes reference to a pre-war understanding with Bock favouring a direct push on the Vitebsk–Orsha region as the priority of 3rd Panzer Group.

36

Furthermore, a report from 3rd Panzer Group noted that in spite of OKH's preference for closing the first ring at Minsk, the army group command decided

before the war to leave the final decision open.

37

Clearly, Hoth and Bock sought to pursue their own preference, effectively seeking to bypass the instructions of Halder and Brauchitsch. The irony is that this was the very same tactic Halder and Brauchitsch had adopted in relation to Hitler's unyielding opposition to Moscow and suggests the OKH leadership were not the only ones engaged in silent

duplicity.

On

the morning of 25 June, the subject of the Belostok–Minsk pocket took on a new urgency at Bock's headquarters when Colonel Rudolf

Schmundt, the Führer's chief military adjutant, arrived and informed Bock that Hitler was worried the proposed encirclement at Minsk was too large and that he feared German forces would prove insufficient to destroy the trapped Soviet units or force them to surrender. Either Bock immediately recognised the futility of pursuing operations further to the east if Hitler was now threatening to close a ring at

Novogrudok, or Bock's sense of soldierly duty and unquestioning loyalty prevented him from adopting the quarrelsome tone with Hitler that he so frequently took with his fellow officers.

38

In any case, he telephoned

3rd Panzer Group and ordered that priority be shifted from securing the Dvina to proceeding now with all speed for Minsk. Hitler's decision on the matter had been deferred until the afternoon and Bock wanted to gain as much ground as possible towards Minsk in the hope of ensuring the lesser of two evils was now adopted. He also contacted

9th and

4th Armies with instructions for the encirclement and an emphasis on haste. Bock's change of heart towards Minsk

did little to improve his standing with Halder as the debate now shifted to where exactly the 9th and 4th Armies would meet, with Halder again seeking a tighter concentration than that favoured by Bock.

39

The renewed wrangling incensed Bock, who was already of the opinion that too much had been forsaken, and his diary reflects the ire of indignation: ‘I am furious, for here we are unnecessarily throwing away a major success!’

40