Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (37 page)

Read Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East Online

Authors: David Stahel

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Modern, #20th Century, #World War II

If the KV-1 represented something of a wonder weapon in 1941, it was an achievement paralleled in innovation and complemented in battlefield performance by the medium T-34 tank. This remarkable machine was heavier and better armoured than the German Mark IV, yet also considerably faster. The main armament surpassed anything on the German models, its wide tracks offered better traction in mud and snow, while the design incorporated angled armour helping to make it impervious to all but the heaviest German anti-tank guns.

59

The sum effectiveness of these innovative enhancements in tank design was largely obscured by the tumultuous events following the start of Barbarossa, but again local encounters revealed the extent of the Soviet advantage. In one such illustration on the first day of the war, forward elements of the

7th Panzer Division, made up primarily of Czech Pz Kpfw 38s backed by Mark IVs, were ambushed by a single Soviet T-34. According to one observer, after hitting one German panzer: ‘[T]he Russian tank rushed

back to its unit by passing [

sic

] approximately 30 German tanks which were dispersed throughout a large area. Several tanks, including mine, tried to destroy the enemy tank using our 37mm gun. These attempts, however, had no effect on the T-34 which we were observing for the first time.’

60

Another German soldier,

Franz Frisch, who served in an artillery regiment recalled: ‘Our men were terrified of the T-34.’

61

Colonel-General

Ewald von Kleist, commander of

Panzer Group 1 in Army Group South, dubbed the T-34, ‘the finest tank in the world’.

62

Fortunately for the Germans the new Soviet tanks were still few in number and suffering from deficiencies in fuel and ammunition, poorly trained crews and flawed tactical employment on the part of inexperienced Soviet officers. Nevertheless, the warning signs were plainly apparent that the Red Army had to be defeated in its stricken and diminished state, or the remarkable potential of Soviet industry would deliver the truly ominous prospect of a reconstituted Red Army.

63

On

the whole, the initial success of Operation Barbarossa was a qualified one at best. From the narrowest perspective, the desired breakthroughs had been achieved and the panzer corps, slowly followed by their infantry support, were rolling eastwards towards their first major objective. Yet the great German blow, both military and psychological, had produced no indication that the Soviet state was paralysed by fear or on the brink of internal collapse. On the contrary, even in the most hopeless of circumstances, Soviet forces were resisting stubbornly, often to the bitter end. The defiant attitude was paralleled by the great majority of the civilian population who, upon hearing the news, spontaneously rallied to the call of the nation.

64

Military losses for the Germans, while sustainable in the short term, were nevertheless unexpectedly high and there was a disturbing realisation that the war would demand a lot more sacrifice before it was over. The vast distances also warranted renewed concern given the dreadful state of Soviet roads and the corresponding unsuitability of the wheeled transports. Finally, and perhaps most worrying, was the inability of the German leadership to find common ground in their strategic outlook – in fact the internal strife had only just begun. Consequently the campaign resembled a perilously wayward and

insecure enterprise, where troubles loomed large on the horizon and the main actors jostled for position to lead

there.

The Belostok–Minsk pocket – anatomy of a hollow victory

While Army Group Centre's advance held the key to German operations in the east, its success was nevertheless tied to the simultaneous progress of the northern and southern army groups, which, beyond their own objectives, also had responsibility for ensuring flank support for Army Group Centre.

Rundstedt's Army Group South was faced with by far the most difficult task, confronting the Soviet

South-Western Front commanded by Colonel-General

Michail Kirponos. As the Ukraine was incorrectly believed by the Soviets to constitute the primary focus of a German invasion, South-Western Front was well endowed with mechanised formations and constituted the strongest of all the Soviet military districts.

65

Accordingly Rundstedt, with only one panzer group at his disposal, had an especially difficult advance and was forced to fend off heavy Soviet counter-attacks. On 26 June Halder stated in his diary ‘Army Group South is advancing slowly, unfortunately with considerable losses.’

66

The Operations Officer at OKH responsible for Army Group South further noted: ‘Russians are standing their ground excellently; down here there is exceptionally systematic command.’

67

The enduring delay caused to Army Group South later had a direct bearing on the dissipation of strength forced upon Army Group Centre, when it was compelled to cover its exposed southern flank. It also later encouraged Hitler's deliberations by inflaming his desire to resolve matters decisively in the Ukraine.

Army

Group North made better progress in its initial days and by 26 June General

Erich von Manstein's

LVI Panzer Corps had established a bridgehead at

Dvinsk on the

Dvina. Yet here Manstein became the victim of his own success, having to pause his operations for six days to await the arrival of Colonel-General

Ernst Busch's

16th Army which was threatened on the right flank as a result of

9th Army's turn south to begin its encirclement east of

Belostok. Manstein was also far ahead of Fourth Panzer Group's second panzer corps, General

Georg-Hans Reinhardt's

XXXXI Panzer Corps, delayed in large part by the above-mentioned Soviet counter-attacks at

Rossienie.

68

Lacking support, Manstein's halt was a prudent measure but, as Halder's diary indicates, it afforded the

Soviets the chance to fall back over the Dvina River

.

Halder also observed that in the Army Group's rear area: ‘Strong wedged-in enemy elements are causing the infantry a lot of trouble even far behind the

front.’

69

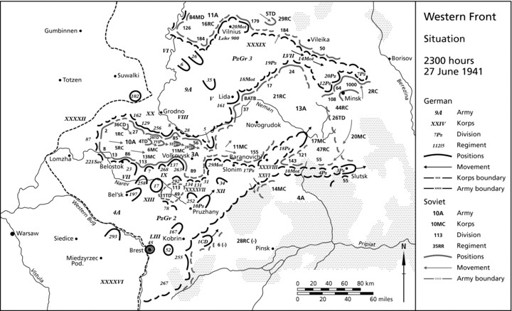

Figure 5.3

Figure 5.3

The motorised divisions had right of way on the roads, which soon led to the opening of a great gap between the small number of panzer divisions and the mass of supporting infantry.

The activity in the northern and southern army groups illustrates the interdependence of each sector on the progress of the war as a whole. Yet, even in this initial period of the war, the inability of the armies to maintain contact between neighbouring units simultaneously, pacify the rear areas, and provide infantry support to the panzer spearheads, speaks strongly of the army's over-extension which was already becoming apparent.

Map 2

Map 2

Dispositions of Army Group Centre 27 June 1941: David M. Glantz,

Atlas and Operational Summary The Border Battles 22 June–1 July 1941

By 26 June, with Pavlov's

Western Front collapsing around him and the combined German panzer groups surging deep into his rear, the front headquarters finally issued orders for a general withdrawal. With the prospect of encirclement all but assured, what remained of the mechanised corps after the furious counter-attacks of the preceding days was now used to force a passage to the east.

70

For its part, Hoth's

Panzer Group seized

Vilnius on 24 June

71

and then General Rudolf Schmidt's

XXXIX Panzer Corps (

7th and

20th Panzer Divisions,

14th and

20th Motorised Divisions) supported by General of Panzer Troops

Adolf Kuntzen's

LVII Panzer Corps (12th and

19th Panzer Divisions and

18th Motorised Division) thrust down to the south-east towards the fortified region north of

Minsk. Although this movement closed the northern pincer of the pocket, it was not without its cost. Here again the Soviet troops proved themselves unrelenting adversaries and, due to a lack of infantry support, the panzers were compelled to assault fixed defensive positions. On 27 June the diary of the 20th Panzer Division noted: ‘The enemy is offering tenacious resistance from modern concrete positions. Our losses are noticeable.’

72

On the following day Hoth's panzer group advised Bock's headquarters: ‘The battle north of Minsk on 28.6 against exceptionally well defended bunkers is considerably more difficult than anything so far…Against such tough defences and constant enemy reinforcements, the 20th Panzer Division could only slowly win ground in the area around Minsk.’

73

Operating on the left flank of the 20th Panzer Division, the 7th Panzer Division had occupied Smolewiecze 20 kilometres north of Minsk by 27 June (see

Map 2

), but the headlong advance over terrible roads had exacted a great toll.

74

By the evening of 28 June overall losses in the 7th Panzer Division constituted a hefty 50 per cent of all the Mark II and III tanks, while the Mark IV tanks suffered 75 per cent losses. As a result, barely a week into the campaign, the division had to request panzer reinforcements from the nearby 20th Panzer Division in order to carry out its next assigned

objective.

75

While overall material losses for the German army at this point remained low, the central importance of the tank and its alarming rate of attrition made its losses particularly critical. With production capacity in Germany still relatively meagre, and Hitler's determination to hold back all new tanks for future operations, the basis of Germany's battlefield mobility and striking power was threatened out of all proportion to the numerical strength of its other arms. The

Red Army's resilience was also making an indelible impression, giving rise to some restive trepidation.

Following the war from his office in

Berlin,

Goebbels noted in his diary: ‘The first big pocket is beginning to close…But they are fighting well and have learned a great deal even since Sunday.’

76

At the front, a liaison officer from Panzer Group 3 visiting the 20th Panzer Division

reported: ‘Of the enemy there exists the impression that his infantry is many times numerically superior and very good to the bitter end. Colonel von Bismark used the expression “

fantastic”.’

77

To the south in Guderian's

Panzer Group 2, spirited Soviet resistance had significantly delayed the progress of

Lemelsen's XXXXVII Panzer Corps on the road to Minsk and accordingly

Guderian was lagging well behind Hoth's progress in closing the pocket.

Western Front's withdrawal east also started creating problems for the panzer group's long left flank, and the commitment of Lemelsen's only motorised division (the

29th) to von Kluge's

4th Army to help contain the pocket and safeguard the panzer group's rear area was hardly sufficient. Even so, Guderian resented having any of his forces removed from his command and was especially perturbed to lose them to von

Kluge for whom he held a keen personal and professional dislike. The antipathy between the two stretched back to past clashes, first in the Polish campaign and later with greater gusto in the Western campaign. Kluge regarded the junior ranking Guderian as a habitual risk-taker and an unwarranted hazard to the army, while Guderian viewed Kluge's caution as outdated and stifling to the new, rapid war of movement he sought to enact.

78

When Guderian received word of 29th Motorised Division's transfer he immediately dispatched one of his officers, Captain Euler, to 4th Army to argue for its immediate reinstatement. Failing this, the request was made that the division remain only so long as absolutely necessary and that it be relieved by elements of the OKH reserve. Euler also carried the request that 4th

Army's XII Army Corps be diverted to secure the panzer group's main supply route or else ‘the secure provisioning of the Panzer Group would stand in question’. A third request appealed for an official order forbidding elements of 4th Army from using the main thoroughfares necessary for the movement of Guderian's reserve panzer corps (General of Panzer Troops

Freiherr von Vietinghoff's

XXXXVI Panzer Corps).

79