Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (30 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The German defeat at Kursk in July/August 1943 marked the beginning of a series of retreats which ended twenty months later when the Russians entered Berlin. In fact, this period has been aptly described as the

Blitzkreig

in reverse. The

Luftwaffe

had long suffered from numerical inferiority, aggravated from the autumn of 1943 by the withdrawal of fighter units for Reich air defence. To this was now added Soviet strategic initiative. Russian pressure along the whole vast front made it necessary to deploy

Jagdflieger

in small groups in order to provide cover everywhere. In doing so, the principle of concentration of force, which might have ensured local air superiority at critical points, was abandoned. No attempt was made to strengthen the German fighter force: virtually all spare capacity went to the Western and Mediterranean fronts.

By June 1944 the

Jagdwaffe

deployed a mere 395 single-engine fighters in the East, on a front which, despite extensive Russian gains, was still more than 1,500 miles long. Against them were ranged a massive 13,500 aircraft, of which just under half were fighters. The odds were great; they would get still greater. To make matters worse, the vital Romanian oilfields were not only threatened by the Russian advance; they were now within range of American heavy bombers based in Italy.

So thinly was the German Army stretched that on occasion Russian armour broke through and overran

Luftwaffe

forward airfields. Emergency evacuations were frequent, and often the ‘black men’ (ground crews, so-called because of the colour of their overalls) had to be left to fend for themselves as best they might. Added to the inevitable loss of spares, this did nothing to aid serviceability. By autumn of that year the Axis allies Finland and Romania were out of the war, while shortly afterwards

Luftflotte 1

was cut off and isolated in Courland. From this time on, fuel shortages bit deep, as they did on all other fronts.

In a last desperate attempt to stem the Red tide, the

Luftwaffe

switched about 650 fighters from the West in late January and early February 1945. While this brought the numbers up to between 850 and 900, it was too little, too late. The Soviet Air Force had expanded at a still greater rate and by now deployed approximately 16,000 combat aircraft. One

Jagdgeschwader

, with about 80 brand new FW 190As on strength, was so limited for fuel that it could only put up four fighters at a time!

As in the first years of the Russian campaign, the use of air power was almost entirely tactical and engagements took place at medium and low levels. The

Jagdflieger

had two main tasks for most of this period: to protect their own infantry from enemy attack aircraft, and to protect their own tank-busting aircraft from enemy fighters. In either case they were usually heavily outnumbered, and when they encountered the élite Russian Guards Fighter Regiments they were sometimes outfought.

The Russian fighter pilots had come a long way since 1941. Apart from adopting pairs and fours as standard fighting units, they tended to fly everywhere at full throttle to keep their speed high. Offensively, this reduced the time between sighting and attacking, thus improving their chances of gaining surprise; defensively, it reduced the chance of their being surprised from astern by increasing the time taken by an opponent to close to firing range, while making greater demands on his time/ distance judgement. Another Russian measure against surprise attack was the habit of flying in large and apparently undisciplined gaggles, with sections twisting and turning at random. As they rarely operated over long distances, they were able to afford a relatively low formation speed over the ground.

Several thousand British and American fighters were supplied to the Soviet Union during the war, of which the P-39 Airacobra was numerically the most important. At home, the Lavochkin and Yakovlev design bureaux produced some truly outstanding fighters. This was done by developing existing machines, which had the further advantage of causing the least disruption to production when switching from one model to the next.

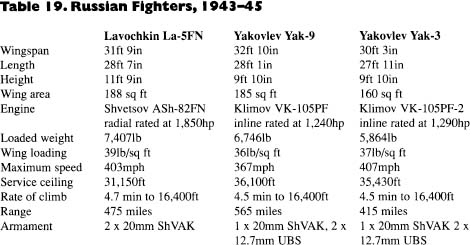

The Lavochkin La-5 was initially the LaGG-3 adapted to take the more powerful Shvetsov ASh-82A radial engine. As the engine of the latter aircraft was a liquid-cooled inline, considerable modification was needed to the forward fuselage. The next step was to cut down the rear fuselage and fit an all-round-vision canopy. To protect the back of the pilot’s head, armoured glass was used. The La-5 was then subjected to considerable redesign. The engine was the new ASh-82FN, with fuel injection. Weight was saved by replacing wooden wing spars with metal ones, and boundary-layer leading-edge slats were fitted. The new model became the La-5FN, which entered service in 1943. Light, well-harmonised controls gave it excellent qualities in the rolling plane while moderate wing loading allowed it to turn tightly.

The final Lavochkin design to enter service in any numbers (from 1944) was the La-7. Although powered by the same engine, it showed marked improvements over the La-5FN, thanks to various small aerodynamic refinements. Although a later model, it did not replace the La-5FN, but is believed to have been introduced as an interceptor to counter the FW 190A-8. Top Soviet ace Ivan Kozhedub gained all his 62 victories while flying Lavochkin fighters.

Alexsandr Yakovlev’s Yak-1 spawned a whole family of new and agile fighters. Numerically the most important of these were the Yak-9, optimised for low-level work, and the Yak-3, a slightly smaller and lighter machine which performed well at the higher altitudes. Exter

nally they were very similar, which made life difficult for a

Jagdflieger

who was trying to decide what he was up against, and both bore a marked resemblance to the Yak-1, except for a cut-down rear fuselage and an all-round-vision canopy. The Yak-9 made its combat début at Stalingrad in December 1942, while the Yak-3 entered service late in 1943. French pilots in the Normandie-Niemen Regiment claimed that the Yak-3 was even smoother to fly than the early Spitfires. It was certainly faster and had a better rate of climb, and whereas the ailerons on the British fighter stiffened up at high speeds, those of the Yak-3 remained light.

The German fighter types on the Eastern Front between 1943 and 1945 were the later variants of the Bf 109G and FW 190A, which have been dealt with in previous chapters. Given that the fighting on the Russian Front took place almost entirely at medium and low levels, it seems surprising that the FW 190A, a dogfighter

par excellence

, was not used by all fighter units. In fact, the demands for this machine were such that there were never enough to go round. Reconnaissance, close air support (the

Schlachtgruppen)

and even anti-shipping units all clamoured for the Focke-Wulf.

The shortage of

Jagdgruppen

meant that close air support units had frequently to provide their own fighter escort, and, as a result, a few

Schlachtflieger

ran up respectable scores in air combat. The most outstanding was August Lambert. Previously an instructor, he arrived at the front in April 1943. At first Lambert scored slowly, but in the Crimea in spring 1944 he had an incredible run of 70 victories in three weeks, 46 of which were scored in the course of three separate days! Shortly afterwards he returned to instructing. He was killed on 17 April 1945 when Mustangs caught him shortly after take-off, his final score 116.

Although the FW 190A was the better machine in the dogfight, many leading Russian Front

Experten

preferred the Bf 109G, despite its nasty qualities during take-off and landing and its inferior rearward vision during combat.

Start by climbing on to the port wing, then walk forward to the cockpit. Grab the framing, then stretch your right leg in past the control column,

ducking under the canopy as you do so. Shuffle down, pulling your left leg after you, and seat yourself on the parachute which is submerged in the metal bucket seat. Now for the straps. Parachute harness first, then restraining straps. For heaven’s sake don’t mix them up—a mistake could be fatal. And strap in tight. If you have to make a wheels-up landing this trip, it will probably hurt anyway, but tight straps help. And if you have to bale out and your parachute harness is at all loose, it’ll make your eyes sparkle!

It’s a tight fit inside. The cockpit cills almost brush your shoulders, so keep your elbows tucked in. Your mechanic lowers the canopy and locks it. If you need to bale out during this sortie you can jettison it. The roof almost brushes the top of your leather flying helmet, while the side transparencies are only inches away. How confined it all is! The seat is very low to the floor and your legs are almost horizontal. This is an advantage in hard manoeuvring, as it retards the onset of grey-out caused by blood draining from the head.

Time to start up. Select one-third flap, trim for take-off, propeller to fine pitch, radiator flaps open, mixture to full rich, pump the yellow priming handle, then open the throttle. A mechanic on the starboard wing inserts a crank and begins to wind the inertia starter, slowly at first, then with ever increasing speed. When it is turning fast enough, he removes the crank and you can now pull the small black starter handle. A few bangs, and puffs of black smoke from the exhausts, then the engine roars into life.

Time to taxi. The ground angle is steep, and the long nose blocks forward vision. You don’t want to hit anything, so swing the aircraft from side to side while looking forward through the quarterlights. The ride is harsh, and you feel every bump. If you ran over a

pfennig

you could tell if it was heads or tails.

Take-off! Throttle lever smoothly back (back to accelerate was standard continental practice) and the Daimler-Benz gives out its distinctive clattering ‘Thor’s Anvil’ song as it winds up. Brakes off, and the acceleration presses you back in the seat. A bootful of right rudder to hold you straight against the torque. Edge the stick forward: the nose rises and at last you can see ahead. Hold it down: if you let it rise too soon it will roll straight over on to its back—not nice! Speed builds up—

185kph—that’s enough; ease back on the stick and let the aircraft fly itself off.

Gear up, flaps up, radiator flaps closed and back on the stick. The 109G climbs like a bird at about 900 metres a minute, indicated speed something over 250kph. The controls are positive if a little heavy, but there is plenty of feel. Level out and ready for action! Flip the safety lid on the control column which covers the gun buttons. Switch on the gun sight, and a yellow circle and bars appears in the sighting glass which is offset to the right, in front of your ‘shooting eye’. You are now ready for anything.

Keep a sharp look-out, especially towards the sun. That’s where they’ll come from. Don’t get too low over the undercast: they’ll see you from miles away against the white background. Actually the view ‘out of the window’ is not so good. The heavy framing of the windshield and canopy could conceal a whole gaggle of Russians, so keep your head moving to peer into the blind spots, especially astern. Weave so that you can check under your tail, and cover your wingman.

Time to go home. Down again, circle the field and line up for landing. Don’t let the speed drop too much. Gear down and full flap. You are very busy, and this is where many 109 pilots come to grief. Nose high and plenty of power as the angle of attack increases and the drag builds. As speed decays through 160kph, the port wing becomes heavy. Ease the stick to the right to counter it, but gently. If speed bleeds off too quickly, drop the nose a tad. Whatever you do, don’t bang the throttle open now: if you do, the torque will roll you uncontrollably to port and you’ve no height left in which to recover. Ease on to the ground at about 135kph. The tyres shriek, throttle forward and suddenly your once graceful bird is jolting and bumping across the grass. Don’t brake hard or you will ground-loop. That’s it. You’re down! You’ve done it!

Experten

As Russian strength grew, the

Jagdflieger

operated in an increasingly target-rich environment. This had its drawbacks. While opportunities to score were plentiful, so were the chances of finding a Russian fighter on one’s tail, and in the final two years of the war there were plenty of competent Russian pilots. The secret of success was to survive, but this

was far from easy. When shooting, the fighter pilot had to concentrate every ounce of his being on his target, oblivious to danger from behind, which, in a multi-bogey dogfight, was never far away. There were two ways of doing this. The first was teamwork, flying with three top-notch pilots making up the

Schwarm

to give cover; the second was keeping the situation controllable.

WALTER NOWOTNY

Perhaps the greatest exponent of the first method was Walter Nowotny of

JG 54

, whose

Schwarm

became famous on the Eastern Front. It consisted of his regular

Kacmarek

Karl ‘Quax’ Schnorrer (35 victories in Russia, 46 total), Anton Döbele (94, all in Russia) and Rudolf Rademacher (90 in Russia, 126 total). In his early days Schnorrer was involved in a series of landing mishaps which earned him the nickname ‘Quax’. The original Quax was an accident-prone cartoon character in training films—the

Luftwaffe

version of Pilot Officer Prune. This notwithstanding, Schnorrer not only did a great job in covering Nowotny’s tail, but later scored eleven victories while flying the Me 262 before being shot down and losing a leg. Of the others, Döbele was killed in a collision with a friendly fighter in November 1943 while Rademacher died in a glider crash a few years after the war.