Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (31 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

Nowotny was an Austrian, and his first victories were scored in July 1941, but he was a relatively slow starter and he took more than a year over his first 50. His fast-scoring days began in June 1943, in which month he reached 100. The next 100 took a mere 72 days, by which time he was the fourth highest scorer, while on 14 October he became the first pilot to reach 250. Five more followed before he was posted to a training wing. In July 1944 he returned to action with

Kommando ‘Nowotny’

, to fly the Me 262. He added only three more to his score before he was killed in action on 8 November 1944.

ERICH HARTMANN

The highest-scoring

Experte

of all, with 352 victories, Hartmann survived the war without a scratch, even though downed many times. He was that rare bird, an unmilitaristic warrior, and spent virtually the entire war in the lower echelons. This allowed him to concentrate on the day-to-day business of air fighting and sur

vival, without getting ensnared in the problems of higher command. His career has been documented in considerable detail, which allows us to gain a remarkably clear picture, not only of his tactics and methods, but how they were formed.

One consistent thread runs through Erich Hartmann’s early years. He was fortunate in his formative influences. His mother was an early aviatrix, who introduced him to gliding when he was 14 years old. When, in early 1942, he learned to fly the Bf 109, one of his instructors was

Experte

and former aerobatic champion Erich Hohagen (55 total victories), who encouraged him to explore the manoeuvre capabilities of the type. In October 1942 he joined

9/JG 52

, and he was lucky again in his commanders.

Kommodore

Dietrich Hräbak (125 victories) and his

Kommandeur

Hubertus von Bonin (77) took a relaxed view of discipline at the front. This was just as well for the less-than-Prussian Hartmann. Under a more rigid commander, such as Karl Borris (43 victories) of

II/JG 26

, his career might have taken a very different course.

Hartmann was equally lucky in his first section leaders. Edmund ‘Paule’ Rossmann (93 victories) was an excellent mentor for the novice. Unable to haul his Messerschmitt around in hard manoeuvres due to an injured arm, Rossmann had been forced to develop stand-off tactics. These consisted of standing back to weigh up the situation, attacking only with the advantage of surprise to make sure of a non-manoeuvring target, then opening fire from long range. This demanded a high degree of marksmanship, which fortunately Hartmann possessed.

Ace fighter pilots are often described as fearless. This is far from the truth. On his first encounter with an enemy aircraft Ernst Udet froze with fear and was unable to fight. Yet he went on to become the highest-scoring surviving German ace of the Great War, with 62 victories. As with Udet, so with Hartmann. On his first mission with Rossmann he lost his leader, panicked, and ended up belly-landing out of fuel far from his base. This humbling experience taught him to control his fear.

Three other section leaders helped shape the tactics of the budding

Experte.

The difficulties of downing the heavily armoured II-2 have been mentioned. Alfred Grislawski (133 victories) taught Hartmann to aim for the oil cooler. Not only did this call for marksmanship of a high order, it required close-range shooting. Hartmann’s first victory, on 9

November 1942, was an II-2, but he paid a high price. Pieces torn off the stricken Russian damaged his aircraft, forcing him to belly-land. The other two were Hans Dammers (113) and Josef Zwernemann (126). Like Grislawski, they taught the novice to get in close before firing.

It was 27 February 1943 before Hartmann, flying as

Kacmarek

to these three, scored his second victory. Shortly after this two new mentors appeared. These were Günther Rall, who replaced von Bonin as

Kommandeur

, and Walter Krupinski (197 victories, 177 in the East). Generally known as ‘

Graf

Punski’ owing to his propensity for living life to the full, Krupinski would have been an outstanding character in any air force. In the air, he was a bar-room brawler type of flyer with a habit of getting himself into impossible situations which he somehow survived. Hartmann was coerced into becoming his

Kacmarek

and under his tuition was encouraged to get in close before firing. Krupinski it was who gave Hartmann the nickname ‘Bubi’ (Boy), and it stuck.

Towards the end of April 1943, Hartmann had acquired eight victories and become a

Rottenführer

(section leader). He was now free to develop his own ideas, which emerged as an amalgam of Rossmann’s carefully considered attacks coupled with the ‘stick your nose in the enemy cockpit’ approach of the others. Many years after the war he described it thus:

I never cared much for the dogfight. I would never dogfight with the Russians. Surprise was my tactic. Get the highest altitude and, if possible, come out of the sun … ninety per cent of my attacks were surprise attacks. If I had one success, I took a coffee break, and watched the area again.

Finding [the enemy] depended purely on being where the action was concentrated on the ground and on visual look-out. Ground stations called us by radio the position of the enemy after a coordinate system on our maps. So we could search in the right direction and choose our best attack altitude. If I covered the sky, I preferred a full-power, sun attack from below, because you could spot the enemy very far away against a white cloudy sky. The pilot who sees the other pilot first already has half the victory.

The second step of my tactic was the point of decision. That is, you see the enemy and decide whether to attack immediately, or wait for a better situation, or manoeuvre to make it more favourable, or not attack at all. For example, if you have to attack the enemy against the sun, if you don’t have enough altitude, if the enemy is flying in broken clouds, you keep your enemy in sight far enough so you can change your attack position in the sun or above the clouds, diving to sell your altitude for high speed.

Then attack. It doesn’t matter if you pick on the straggler or the guy out of formation. The most important thing is to destroy an enemy aircraft. Manoeuvre quickly and aggressively and shoot in close, as near as possible to ensure the hit and save rounds. I told my men, ‘Only if the windshield is filled up, then pull the trigger.’

Finally break or reverse. If you hit and run, think about survival. Immediately check six [o’clock] and reverse. Clear the area for potential attackers or pick a new point of re-entry and do it again, if you have the advantage.

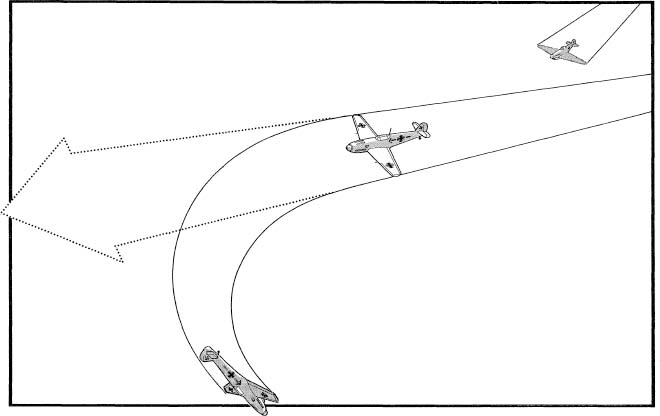

Fig. 24. Hartmann’s ‘Last Ditch’ Evasion Manoeuvre

As the enemy fighter approached

,

Hartmann used rudder to point his fighter in a slightly different direction from the way it was going

,

to mislead the attacker into misjudging the amount of deflection required. When his opponent opened fire

,

Hartmann slammed the stick into the far corner of the cockpit

,

putting his

Messerschmitt into the first half of an outside oblique loop.

Hartmann encountered the enemy in the air on more than 800 occasions, and it was inevitable that sometimes he became a target. To counter this he had his own particular method:

Fly quickly straight ahead, and push the rudder so you fly a slight straight-ahead skid that will not be recognised by the attacker. If he opens fire, you push for negative Gs down left or right, not forgetting through the whole manoeuvre to push the rudder. Your attacker will hang with negative Gs in his belt, unable to pull the trigger. With that manoeuvre I saved my life several times.

Not until the middle of 1943 did Hartmann really get into his stride. At dawn on 7 July he had 21 victories. By dusk on 20 September that had risen to 100. The legends started. Hartmann is popularly supposed always to have flown a Bf 109G with a bleeding heart insigne below the cockpit inscribed with the name ‘Usch’ (his fiancée), but at least one of his machines carried the legend ‘Dicker Max’ in the heart! His personal aircraft is often depicted with a black tulip pattern painted on the engine cowling. In fact he flew a machine marked in this way on five or six occasions only, in the Ukraine. Success eluded him on these missions, so he abandoned it. Finally, he was widely supposed to be known to the Russians as ‘The Black Devil’, a name widely at variance with his unmilitary call-sign of ‘Karaya [Sweetheart] One’, which of course was well known to his opponents.

Over the next months Russian after Russian fell before Hartmann’s guns, and on 1 July 1944 he reached 250, the fifth and last pilot to do so. Still his tried and proven methods served him well, while less cautious

Experten

fell by the wayside. In March 1945, his score at 336, he was transferred to

JG

7 to fly the Me 262 jet fighter. But, with the airfield under constant attack, flying was limited, and shortly afterwards he returned to

JG 52

, to finish the war in Romania. It was there that he encountered American Mustangs. He accounted for seven in all, but on

one occasion he was trapped by eight American fighters and forced to bale out through fuel shortage, even though he had not been hit.

Shortly after this, the war ended. Erich Hartmann’s final score was 352, of which 260 were fighters. He flew only the Bf 109G, of which he said:

It was very manoeuvrable, and it was easy to handle. It speeded up very fast, if you dived a little. And in the acrobatics manoeuvre, you could spin with the 109, and go very easy out of the spin. The only problems occurred during take-off. It had a strong engine, and a small, narrow-tread undercarriage. If you took off too fast it would turn [roll] ninety degrees away. We lost a lot of pilots in take-offs.

Erich Hartmann’s score will never be matched. Few air forces have as many as 352 aircraft to lose, let alone to one man!

| 11. THE JET ACES |

By 1944, piston-engine fighters were nearing the limits of what was technically possible, and tremendous increases in power were needed to make quite minor gains in performance. Further progress depended on a new form of propulsion. This was available in the form of the reaction motor, either the gas turbine or the rocket. Germany was well advanced in both, but the desperate war situation demanded that they be rushed into service before the technology was really mature. Nevertheless, the

Luftwaffe

had no fewer than three new types of jet or rocket fighter in service at the war’s end. While this was a remarkable achievement, it was, again, too little, too late. The Allies dominated the sky over the Third Reich, and quality was ground down and defeated by quantity.

Two of the new fighter types achieved little, produced no

Experten

and can therefore be dismissed after a cursory examination. These were the Heinkel He 162

Volksjäger

and the Messerschmitt Me 163

Komet.

The

Volksjäger

or People’s Fighter was a last desperate attempt to build up the numerical strength of the

Jagdwaffe

very quickly. The keynote was ‘quick and cheap’, with mass production by semi-skilled labour using readily available materials, and with the aircraft mass-flown by semi-skilled pilots who, at least initially, were to convert on to type direct from glider training.

Unusually, the BMW turbojet was mounted dorsally, where it largely obscured the rear view from the cockpit. The aircraft itself suffered from instability, and only a handful were ever encountered in action.

Experten

known to have flown it, although not necessarily in action, include Heinz Baer, of whom more later; Herbert Ihlefeld (130 victories); and Paul-Heinrich Dahne (98 at least), killed on a training flight in an He 162 on 24 April 1945.