Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (29 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

The Dora was the most formidable piston-engine fighter to enter

Luftwaffe

service in any numbers. In sheer performance it outmatched the Thunderbolt and Lightning, and in some respects even the Mustang. The accompanying table shows it to be generally inferior to the Spitfire XIV and Tempest V. Its wing loading was so much higher that, speed for speed, it would have been out-turned with ease. Only in rate of roll did it have any real advantage. This poses the question: why did it not get cut to pieces every time by the British fighters?

The answer lies in the nature of air combat. A level playing field is no part of the game. Surprise is the dominant factor: flying the best fighter in the world is of little avail if its pilot is caught napping. The tactical fighter battles over Western Europe usually started with a surprise bounce, with the attacker making full use of the sun, or of cloud cover. The ‘Dora’ pilots knew this full well, and took advantage of it. Only when the engagement degenerated into a confused multi-bogey dogfight would pilot quality and aircraft quality begin to tell. As they had done since 1940, the

Jagdflieger

adopted the old saying: ‘he who fights and runs away …!’ This policy maximised effectiveness and minimised casualties, as it had done throughout the war.

There was one other relevant factor which offset poor training. Thrown into the crucible, if the youngsters survived their first sorties they gained combat experience rapidly. This was in stark contrast to the better trained Allied flyers, many of whom had little opportunity of meeting the enemy. To digress for a moment, between 1943 and the end of the war, over 5,000 fighter pilots flew operationally with the US Eighth Air Force. Of these, just 2,156 (43 per cent) claimed so much as a share in a victory! Like every other human activity, air combat demands practice. Raw Allied pilots got far less than their opponents, and were thus very much at risk if they happened upon an

Experte.

Experten

Heavily overmatched, at risk from the time they began their take-off roll to the time they switched off their engines after a mission, there was little scope for raw, young pilots, with perhaps a dozen hours on type, to make their mark. Staying alive was difficult enough, let alone running up a score, although a handful did moderately well. By and large,

Experten

who succeeded against the Allied tactical fighters had gained experience in less demanding scenarios, and had developed that strange sixth sense known as situational awareness.

JOSEF TIPS’ PRILLER

‘Pips’ was just five feet four inches tall, but a giant in a fighter cockpit, one of the few to register over 100 victories entirely against the West. He started the war with

II/JG 51

and flew with them throughout the French campaign and the Lattle of Britain, during the latter stages of which the

Geschwader

was commanded by Werner Mölders. His style of leadership was marked by a quirky sense of humour, and he was reputed to be the only fighter leader to be able to make Goering laugh when things were going badly. The following comment on an incident during the Battle of Britain is typical:

I remember one occasion when a lad who hadn’t, as we used to say, tasted much English air, lost sight of our formation after some frenzied twisting and turning about the sky: he had dived steeply and was over the outskirts of London. He should have stayed with the

Staffel

instead of chasing off on his own. When he grasped the situation he called for help: ‘Come quickly! I’m on my own over London.’He hadn’t called in vain. By return post, as it were, his

Schwarm

leader, whom he couldn’t see but who could see him clearly and had followed astern and above him, gave the comforting message; ‘Hang on a second and you’ll have a couple of Spitfires behind, then you won’t be alone any longer.’

By 19 October Priller had scored his twentieth victory, and a month later he was transferred to

1/JG 26

as

Staffelkapitän.

The next few months were quiet, but when the RAF commenced Circus operations in the early summer of 1941 he began scoring rapidly, claiming 20 victories between 11 June and 14 July, including eighteen Spitfires. The last of these was of particular interest as the attack was made from head-on at 33,000 feet against the middle Spitfire of a section of three flying in line astern. Priller seems not to have seen the leader. In the rarefied air at high altitude, engine power falls markedly, while, to obtain sufficient lift, the angle of attack of the wings has to be increased. At 33,000 feet an aircraft in level flight adopts a distinct nose-up attitude, which restricts still further the already limited view ahead. Priller took full advantage of this by attacking in a shallow climb, closing to 100 metres’ range. The Spitfire pilot baled out, but then Tips’ had to dive away to escape the attentions of the third fighter.

Further successes followed, and Priller became

Kommodore

of

JG 26

on 11 January 1943, at which time he was the leading

Experte

of the

Geschwader.

His standards were high, so much so that, when in February 1943

III

/

JG 54

transferred from the East to come under his command, he refused to declare them operational for some considerable time.

Priller’s score continued to mount, and twelve victories between 5 and 13 April took it to 96. During this year he also conducted a considerable amount of weapons and other testing, while increased responsibilities on the ground restricted his operational flying. His century was a long time in coming.

When, on 6 June 1944, the Allies landed in Normandy,

JG 26

was caught unprepared. Two

Gruppen

were in the process of moving to bases further inland; the third was in southern France. Only the

Stab

was in a position to mount an immediate sortie, and this was flown by Priller himself, with his regular

Kacmarek

,Heinz Wodarczyk. Taking full advantage of low cloud, the two FW 190 pilots made a full-throttle

strafing run over ‘Sword’ Beach, then returned the way they came. They were the only

Luftwaffe

presence over the invading forces that morning.

Priller’s 100th victory came on 15 June when leading a fighter sweep over Normandy. His mixed formation of

II

and

III/JG 26,

and

III/JG 54,

encountered a formation of American heavy bombers with a strong fighter escort. His combat report read:

I made a front quarter attack on the first box from the same altitude, and obtained several strikes on one of the Boeings on the left of the formation. After a battle at close range with the very strong escort, I attacked a formation of about 20 Liberators from head-on. I fired at the Liberator flying in the left outboard position in the first Vic, and saw strikes on the cockpit and both port engines. After I dived away, I saw the Liberator fall away from its formation with bright flames coming from three engines. I did not see it hit the ground because of the continuing air battle.

A double command now came Priller’s way, which restricted his flying still more. His 101st and final victory was a P-51 Mustang on 12 October. Only eleven heavy bombers featured in his overall tally: as a general rule he preferred to take on the escorts. Priller’s final mission was leading

JG 26

in

Operation ‘

Bodenplatte’

on 1 January 1945. At the end of that month he was transferred to a staff job.

‘Pips’ Priller’s greatest value in the post-invasion period was not the number of victories scored, but his leadership and example. Of the eight pilots who scored 100 or more against the Western powers, only Adolf Galland (103); Egon Mayer (102) and Josef Priller (101) did so exclusively in Western Europe. It is also worthy of note that RAF top scorer Johnnie Johnson saw fit to record in his book

Full Circle

that most of Priller’s claims could be confirmed from Allied records.

ADOLF GLUNZ

The little-known

‘

Addi’ Glunz had a truly remarkable record. By

Jagdwaffe

standards his victory tally of 71, three of which were in the East, was good but not exceptional. What was unusual was that, in 574 sorties, the vast majority of which were over Western Europe, and in which he encountered the enemy on 238 occasions, he was never once shot down or wounded. The nearest he ever came to losing an aircraft was on 13 October 1944, when a broken oil pipe caused his motor to seize during a fight with two Thunderbolts. Engineless, he evaded the American fighters by hard turns, followed by a near-vertical dive into cloud. Having shaken off his pursuers, he made a good wheels-up landing in a field.

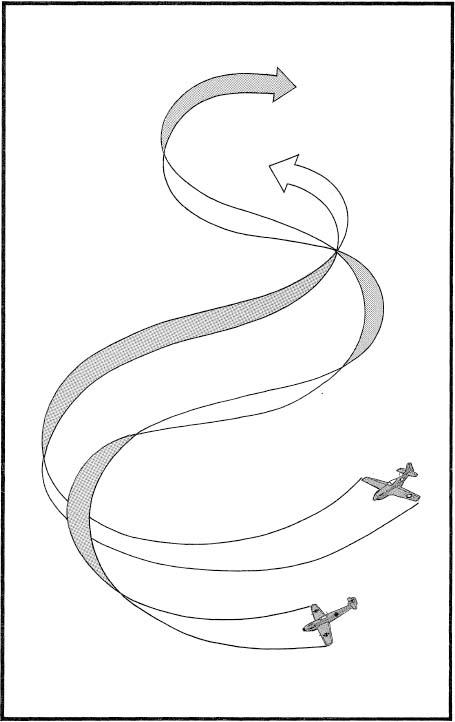

Fig. 23. The Spiral Climb

Heinz Knoke of

JG 11

was one of many German fighter pilots to use the spiral climb as a means of evading American escorts. With the angle and distance constantly changing, it made his Messerschmitt an almost impossible target. The spiral dive was an alternative, for the same reasons.

Glunz joined

4/JG 52

on the Channel coast in March 1941, but his first three victories came with this unit during the first three weeks of the Russian campaign. He was then sent back to the Channel, to

41/JG 26.

Having converted to the FW 190A, his score slowly mounted.

Addi Glunz was both determined and persistent. A confused multi-bogey battle on 13 March 1942 separated him from his unit. Alone but undaunted, he stalked a Spitfire formation out to sea, picked one off in a surprise attack, then damaged a second before making good his escape. The Schweinfurt raid of 17 August 1943 saw a further example of his coolness. As

II/JG 26

lined up to assault the bombers on their homeward journey, they were bounced by Thunderbolts and scattered. In the general confusion Glunz dodged the escorts and shot down a B-17. His was the only bomber success of the action.

Proficiency in instrument flying led to his 45th victory on 14 November. Daylight nuisance raids by single Mosquitos did little actual damage but, by activating air raid warnings across the Reich, caused considerable disruption to industry. Addi took off alone and, directed by ground control, climbed through heavy cloud to 28,000 feet. Soon he saw the Mosquito skimming along below, a few hundred feet above the dazzling white cloud tops. His FW 190A was above its best height here, but a gentle dive brought him below and behind. Slowly he closed on his prey, then with it firmly in his sights he pressed the firing buttons. This was the first of three Mosquitos that fell to his guns.

Glunz’s greatest day in combat came on 22 February 1944. By now a

Staffelführer

(a probationary

Staffelkapitän),

he led

5/JG 26

into action against the American heavy bombers. In the first mission of the day he shot down two B-17s and forced a third out of formation. That afternoon he claimed another two B-17s and a Thunderbolt. Only three B-17s and the P-47 were confirmed, but these brought his score to 58.

The invasion and its aftermath saw Allied fighters fill the skies, yet Glunz continued to fly, to survive and to score. The weather was often on the side of the

Luftwaffe:

heavy cloud provided a useful means of escape when things got tough. This was the case on 10 June. Hurtling

around the cloud banks, he got behind an American fighter and sent it down in flames before seeking the foggy interior of a cumulus to avoid retribution. Inside, he almost collided with the tail of another American. As they hurtled out of the cloud he pressed the firing buttons and his shells tore into the doomed fighter. But as he fired, he saw the American’s wingman barely 30 feet away! Without ceasing to fire, Addi kicked the rudder to skid his Focke-Wulf sideways, liberally spraying the other aircraft at close range. It fell away. All three victories were confirmed, bringing his total to 64.

Addi Glunz survived

Operation ‘

Bodenplatte’

, during which he was credited with the destruction of five aircraft on the ground. In February 1945 he was assigned to

JG 7

to convert to the Me 262, but, so far as is known, he never flew the jet operationally. Of his 68 victories in the West, 20 were four-engine bombers.

To what did Glunz attribute his success? He was an expert aircraft handler, owing to his having been an aerobatic pilot from an early age. His exceptional distance vision gave him a tactical advantage; in this he is similar to American ace Charles Yeager. He was a natural shot, and there were all too few of them in any service. Finally, when he first joined

JG 26

,he came under the influence of Adolf Galland, whose principle was: ‘Never abandon the possibility of attack. Attack even from a position of inferiority, to disrupt the enemy’s plans. This often results in improving one’s own position.’

| 10. RETREAT IN THE EAST |