Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (25 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

I came up behind him to see what kind of reaction I would get from the tail gunner. Nothing happened. I got closer; still nothing. By then I was flying in formation [with the B-17], on the right side. I looked across at the tail gunner and all I could see was blood running down his gun barrels. I could see into Brown’s plane, see through the holes, see how they were all shot up. They were trying to help each other. To me, it was just like they were in a parachute. I saw them and I couldn’t shoot them down!

Stiegler escorted the badly damaged B-17 out over the North Sea, saluted it and returned to his base. He had committed a court-martial offence, but, as he said later, ‘I saw the men; I just couldn’t do it!’ In this he was not alone. Stiegler, who now lives in Canada, ended the war flying Me 262s with

TV 44

.

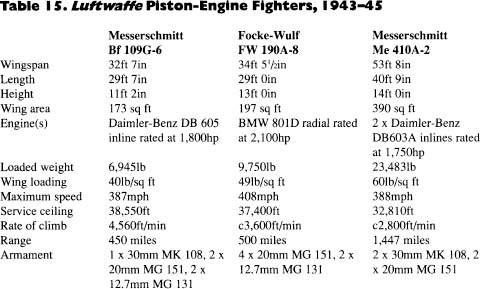

It may seem strange that the FW 190A, a much later design than the Bf 109, used the latter to protect it. The fact is that the performance of the FW 190A fell away above 24,000 feet, which was an average attack height for the B-17. Above this level the later variants of the Bf 109 were superior and it was better suited to the air combat mission. The Bf 110 was largely supplanted in the

Zerstörer

role by the Me 410, but in the presence of escort fighters this twin-engine fighter was far too vulnerable. Eduard Tratt of

II/ZG 26

, the top-scoring

Zerstörer

pilot of the war with 38 victories, was shot down and killed while flying an Me 410, by Mustang pilot Jack Oberhansley on 22 February 1944.

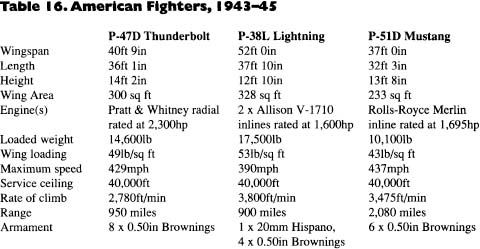

Of the USAAF escort fighters, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt was the most widely used in the initial stages. Large and heavy, its great strengths were in the dive, its high rate of roll and its heavy armament of eight 0.50in machine guns. The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was a strange twin-engine, twin-boom design. Very fast at altitude, it was generally outmatched by the German single-seaters in one-versus-one combat. Fortunately for its pilots, one-versus-one combats rarely occurred, and teamwork compensated for many of its shortcomings. The most important type was the North American P-51 Mustang. Good at low altitude in its original form, it was re-engined with the Rolls-Royce Merlin, making it a match for the Bf 109 and FW 190. Its great strength was its long range, which allowed it to rove the length and breadth of the Third Reich. Once it entered service in numbers, no German fighter pilot could ever feel safe from attack.

Note:

For anti-bomber work a few Me 410s were armed with the 50mm BK 5 cannon. This carried only 21 rounds, had a slow rate of fire and severely reduced the aircraft’s manoeuvrability.

Experten

Steel nerves and marksmanship were the qualities needed to do well against the American heavy bombers, plus an element of luck to survive running the gauntlet of the defensive fire time after time. These were possessed to the full by Herbert Rollwage

of II/JG 53

, the leading heavy bomber

Experte

, who accounted for no fewer than 44 ‘heavies’ in his total of 102. Only eleven of his victories were scored on the Russian Front; the rest were all against the West, including twenty over Malta. He survived the war.

GEORG-PETER EDER

Although his tally of 78 victories places him low (equal 155th) on the overall list of

Experten

, Eder had one of the most amazing records of the whole war. Shot down seventeen times,

he was wounded, often severely, on twelve different occasions. His score might have been far higher if he had not on many occasions declined to finish off a damaged adversary. While this smacks of propaganda, it has since been confirmed from Allied sources. His aircraft became known as ‘Lucky 13’ to those whom, their aircraft badly damaged, he allowed to escape. For this he was probably the most deserving of all the

Experten

who survived the war.

Eder joined

JG 51

on the Channel coast in December 1940 but failed to score. Transferred to the East for ‘Barbarossa’, he then accounted for ten Russian aircraft before being badly wounded on 24 July 1941. In 1942 he returned to operations with

7/JG

2, and as related earlier, helped develop tactics against USAAF bomber formations in conjunction with Egon Mayer. Here he describes an action on 14 July 1943:

I pushed the black button on the right of the panel and the three yellow rings and cross flicked on in the sight glass. I was leading the first four of the

Gruppe

, with one on the left and one on the right, just back, and the fourth behind them in the centre, higher—the same formation with our

Schwarm

in the

Gruppe

as was flown by the

Gruppen

in the

Geschwader

. We were doing about 450km/hr now and were coming down slightly, aiming for the noses of the B-17s. There were about 200 of us attacking the 200 bombers but there was also the fighter escort above them. We were going for the bombers. When we made our move, the P-47 s began to dive on us and it was a race to get to the bombers before being intercepted. I was already close and about 600 feet above and coming straight on; I opened fire with the twenties at 500 yards. At 300 yards I opened fire with the thirties. It was a short burst, maybe ten shells from each cannon, but I saw the bomber explode and begin to burn. I flashed over him at about 50 feet and then did a chandelle. When I had turned around I was about a thousand feet above and behind them, and was suddenly mixed in with American fighters.Straight in front was a Thunderbolt, as I completed the turn, and I opened fire on him immediately, and hit his propwash. My fire was so heavy his left wing came off almost at once and I watched him go down. By now I had only three fighters with me—my lead

Schwarm

—the others had split away in the attack. We flew south, ahead, for a few seconds, preparing for another strike at the bombers and then, coming from above, I saw them. I called a warning:

‘Indianer über uns!’

, and as they came in behind us we banked hard left. There were ten P-47s and four of us and we were all turning as hard as we could, as in a Lufbery. I was able to turn tighter and was gaining. I pulled within 80 yards of the P-47 ahead of me and opened fire. I hit him quickly and two of the others got one each, so that in a minute and a half three of the P-47s went down. The pilot of the one I hit baled out and I saw his ‘chute open. But one of my men had been shot down and there were now three against seven and I called on the radio for an emergency dive to get away:

‘Nacht unten vereisen!’

, and we all rolled over and did a Split-S and dived with full throttle.

The Split-S was a standard

Jagdwaffe

escape ploy. Emergency power caused a lot of smoke from the exhausts, and often caused Allied pilots to believe that a German fighter was badly hit and going down. In this case the Americans did not follow, possibly because the Thunderbolt was not at its best at low level.

Of Eder’s 78 victories, 36 were four-engine bombers. Later in the war he claimed twelve victims while flying the Me 262 with

Kommando ‘Nowotny

’ and

JG

7. Characteristically, he ended the war in hospital after being shot down by Mustangs.

WALTHER DAHL

The operational careers of Eder and Walther Dahl have striking similarities. Both flew on the Channel coast in 1940 and 1941 without success; both claimed their first victories in the East on the first day of ‘Barbarossa’; both flew aircraft with the number 13; and both were credited with the destruction of 36 heavy bombers. Dahl’s score of 128, amassed in some 600 sorties, included 77 on the Eastern Front. It was Dahl who pioneered the

Gefechtsverband

in 1944 and did much to ensure its success. On 30 November of that year he was placed under house arrest by Goering personally for refusing to take off in appalling weather. Within a matter of weeks he was appointed Inspector of Day Fighters, a position he held until the end of the war.

| 8. RED SKY AT NIGHT, 1943–45 |

By 1943 new blind bombing aids and developing techniques allowed the RAF to attack with a fair degree of accuracy, even on moonless nights and in cloudy conditions. This made life far more difficult for the defenders, who now had to get much closer to the bombers before they could obtain visual contact. Between the beginning of March and the end of June German night fighters accounted for roughly 700 bombers, but this apparently horrific loss represented only about four per cent of the total sorties flown and was easily made good. At least ten per cent was needed to make the British loss rate prohibitive.

The greatest shortcoming was the German

Himmelbett

system of close control. Operating on a narrow frontage, the bomber stream crossed only a handful of

Himmelbett

zones on its way to the target. The few night fighters allocated to these zones had more targets than they could possibly handle, while the rest of the force had nothing. Typically, only about 50 of the 300 or so night fighters available were brought into action against any one raid, and the majority of these were unsuccessful.

This was wasteful of resources. Better results could have been achieved by scrambling all fighters in areas not directly affected and allowing them to freelance in the bomber stream. A few

Experten

had already experimented in this manner, but it took many months and a major disaster before it became general practice. The major disaster was the week-long Battle of Hamburg, which commenced on the night of 24/25 July 1943.

Shortly before midnight on 24 July, early warning radars detected a force of RAF bombers far out to sea. As the plot neared the coast, night

fighters were scrambled. So far it was a routine heavy raid by several hundred bombers. Then, without prior warning, the picture on the radar screens changed. Instead of hundreds of contacts, there were thousands! The screens were full of them—completely saturated. All semblance of tracking was lost. With this the ground control system was paralysed. The chaos on the ground was only matched by that in the sky. Airborne that night was Wilhelm Johnen of

3/NJG 1

:

… my sparker [radar operator] announced the first enemy machine on his Li [radar]. I was delighted. I swung round on to the bearing in the direction of the Ruhr, for in this way I was bound to approach the [bomber] stream. Facius proceeded to report three or four pictures on his screens. I hoped that I should have enough ammunition to deal with them!

Then Facius suddenly shouted: ‘Tommy flying towards us at a great speed. Distance decreasing … 2,000 metres; 1,500 … 1,000 … 500 …’

I was speechless. Facius already had a new target. ‘Perhaps it was a German night fighter on a westerly course,’ I said to myself, and made for the next bomber.

It was not long before Facius shouted again: ‘Bomber coming for us at a hell of a speed. 2,000 … 1000 … 500 … He’s gone’.

‘You’re crackers, Facius,’ I said jestingly.

But soon I lost my sense of humour, for this crazy performance was repeated a score of times and finally I gave Facius such a rocket that he was deeply offended.

This tense atmosphere on board was suddenly interrupted by a ground station calling: ‘Hamburg, Hamburg. A thousand enemy bombers over Hamburg.’