Luftwaffe Fighter Aces (26 page)

Read Luftwaffe Fighter Aces Online

Authors: Mike Spick

This performance was repeated in fighter after fighter as their on-board radars showed contact after contact, all apparently moving at high speeds. The British were dropping Window—bundles of aluminium strips cut to length to match the characteristics of the German radars, which showed each bundle as though it were a bomber.

The

Nachtjagdflieger

, unable to differentiate between Window and bombers, fruitlessly chased spurious contacts around the sky. In fact, there was a difference, but in the confusion it mainly went unnoticed. Window clouds were virtually stationary, and on the radar screens the fighter appeared to close on them very rapidly; by contrast, the echo from a genuine bomber would have a much slower relative speed (fighter speed minus bomber speed).

Airborne that night was Bf 110 pilot Hans Meissner (final score 20 victories) of

2/NJG 3.

After several futile chases after Window clouds, his radar operator Josef Krinner noticed that whereas most contacts on

his screen were fast-moving, one seemed to be almost stationary. As this was more like contacts obtained on previous nights, he directed his pilot towards it. Eventually Meissner gained visual contact with a Stirling and shot it down in flames. This was, however, exceptional. The

Nachtjagdflieger

gained few successes during that or the following nights. Shorn of its defences, Hamburg was devastated.

The greatest weakness of the German air defence system was that too many of its detection systems used the same wavelengths, with the result that Window jammed the lot. The painstakingly built-up German night air defence system lay in ruins. New radars were desperately needed but these were not immediately available. The

Luftwaffe

was forced to seek other means to redress the balance as a matter of desperate urgency.

Fortunately for the Third Reich, other means were to hand.

Himmelbett

had long had its critics, mainly because it signally failed to employ more than a fraction of the available fighter strength at any one moment. Means to remedy this were already in the pipeline, under the names of

Wilde Sau

and

Zähme Sau

(Wild Boar and Tame Boar). The disaster at Hamburg was the catalyst which thrust them to the fore.

Wilde Sau

was the brainchild of former bomber pilot Hans-Joachim (‘Hajo’) Herrmann. Interestingly, it exploited the very success of the bombers. Once a raid had begun, fires on the ground provided a backdrop against which bombers were visible from above. Combined with searchlights, this illuminated the area for fighters to intercept visually. When there was light cloud over the target, the searchlights playing evenly on the underside formed a

Mattscheibe

(literally, ‘shroud’) against which bombers were clearly visible from above.

Wilde Sau

fighters, single-seat Bf 109s and FW 190As, could be used under these conditions given that the flak ceiling was limited, allowing them to operate freely above it.

The next problem was how best to get the short-range

Wilde Sau

fighters to the right place at the right time. Germany was networked with radio beacons for navigational purposes. When the likely target had been deduced, the

Wilde Sau

fighters were assembled at a nearby

radio beacon, flying left-handed orbits at preset heights by

Staffeln.

Once the attack commenced they were ordered into the area, there to hunt visually. It was of course an expedient. The bombing could not be minimised: all that could be done was to inflict maximum casualties over the target area.

Zähme Sau

, pioneered by Viktor von Lossberg, had many features in common with

Wilde Sau.

However, it differed primarily in that it was flown by longer-legged, twin-engine fighters and was intended to intercept before the target was reached. The fighters were scrambled early to orbit a radio beacon on the projected course of the bomber stream. Often they were moved from beacon to beacon as circumstances dictated.

Unlike

Himmelbett

, only a loose form of ground control was exercised in the form of a running commentary on bomber movements as a whole. The radars might be jammed, but the Window trail was a fair indicator of the track of the bombers. But, just to make life interesting, the British became adept at making spoof raids, with a handful of aircraft laying Window while the main force made radical course changes to throw off its pursuers. To complicate matters still more, British communications jamming had by now reached a fine level of sophistication.

Once established among the bombers, the fighters operated as best they might. At least they knew that if Window jamming was present, the bombers could not be too far away. One technique was to fly to where the Window was thickest and search visually. Like the day fighters at this time, the night fighters followed the course of the bombers while fuel and ammunition lasted, then landed at the nearest available airfield. What was called the

Luftwaffe’s

‘migratory period’ commenced.

Zähme Sau

became the backbone of the

Nachtjagdflieger

for the rest of the war, made even more effective later with new electronics.

The summer of 1943 saw two more hazards emerge. Unlike the

Luftwaffe

, the British had persevered with night intruders, and now Mosquitos took to loitering in the vicinity of known night fighter airfields, waiting to catch the unwary. To counter them, patrols of Bf 110s were

flown, but the heavily laden night fighter was too slow to be effective. During the whole of 1943 only four Mosquitos fell to night fighters, and at least some of these were bombers rather than intruders.

Theoretically it had long been possible for the British to send night fighter escorts with their bombers. That they had not done so earlier was due to the impossibility of telling friendly bombers from German fighters before visual range (and firing range for the bomber gunners) was reached. But by the summer of 1943 they had developed a passive detector that homed on German radar emissions.

On 17 August, with a major bombing raid outbound over the North Sea, German ground radar detected a small group of aircraft off the Frisian Islands, flying at typical heavy bomber speeds. Five Bf 110s of

IV/NJG 1

were vectored to intercept. Of the five, one turned back with engine failure. Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer (121 victories) aborted after being damaged by ‘friendly’ flak. The three remaining Messerschmitts bored on. Reaching the area, they switched on their radars and commenced to search.

Georg Kraft was in a gentle left turn when he was suddenly hit from astern by a fusillade of 20mm cannon shells from a Beaufighter. He nosed down, only to be hit again, set ablaze and sent plunging vertically into the sea. Kraft (15 victories) was never seen again. Close by was Heinz Vinke.

Unteroffizier

Gaa, his gunner, had a grandstand view of Kraft’s demise. The Beaufighter was astern, off to the right, and slightly lower. Gaa warned Vinke, who at once broke hard into it. The British pilot gained visual contact just in time and turned inside the Messerschmitt, firing from very close range and barely avoiding a collision as he did so. Ripping through the German fighter, 20mm shells wounded Gaa and the radar operator and tore the control column from Vinke’s hands. All three German crewmen baled out of their stricken fighter, but only Vinke survived. He was rescued after eighteen hours in the sea, only to succumb to Spitfires in daylight six months later, his final score 54. Shortly afterwards, the third Bf 110 fell to a second Beaufighter.

This was a significant defeat for the

Nachtjagdflieger.

All three aircraft were lost for no result, and two

Experten

were shot down. It was a triumph for British electronics expertise, and a harbinger of things to

come. The double victor, Bob Braham, had not yet finished with the

Experten.

On 29 September he shot down August Geiger (53 victories) over the Ijsselmeer. Geiger baled out successfully but was drowned.

The first

Wilde Sau

mission was actually flown before the Hamburg raids. The flak failed to limit its firing, but twelve single-seaters, led by Hajo Herrmann, attacked anyway, claiming twelve bombers. The original unit,

Kommando ‘Herrmann’

, was quickly expanded to full

Geschwader

strength, although two

Gruppen

had to ‘borrow’ fighters from day units on the same bases. This led to friction between personnel: round-the-clock usage reduced serviceability to unacceptably low levels. But, as successes mounted, the

Geschwader

,

JG 300

, was given its own complement of aircraft, and two more

Wilde Sau Jagdgeschwader

were formed.

Wilde Sau

suffered from many of those weaknesses that had been the downfall of illuminated night fighting. Although making visual contact with the enemy was far easier, instrument flying and navigation at night was just as difficult as it had ever been. This was particularly hard on the boys drafted in from training schools, and the accident rate was very high. Many

Wilde Sau Experten

came from bomber or transport units; they could navigate about Germany quite happily in darkness, and could consistently land at night without incident. They were the exception.

The most successful of all was Friedrich-Karl Muller, universally known as ‘Nasen’ Muller, both on account of his truly aristocratic proboscis and to distinguish him from day fighter

Experte

Friedrich-Karl ‘Tutti’ Muller (140 victories). Nasen was an old

Lufthansa

hand who had spent the early part of the war flying bombers and transports. A founder member of

Kommando ‘Herrmann’

, he claimed 30 victories in 52 night missions, 23 of them as a

Wilde Sau

pilot.

The high-water mark of the

Wilde Sau

units came in the late summer of 1943, but with the onset of autumn their star began to wane. No longer were they aided by light summer nights: the weather clamped in and accidents rose. The Bf 109 came to be preferred over the FW 190A for night work: a bad landing simply wiped off the undercarriage and left the aircraft right side up, whereas the more sturdy Focke-Wulf tended to go over on its back. In winter, less experienced pilots were unable to make their way down through heavy cloud and icing; instead, they abandoned undamaged fighters and took to their parachutes.

Wilde Sau

units remained in service well into 1944, but they were never again as effective and were often called upon to fly by day.

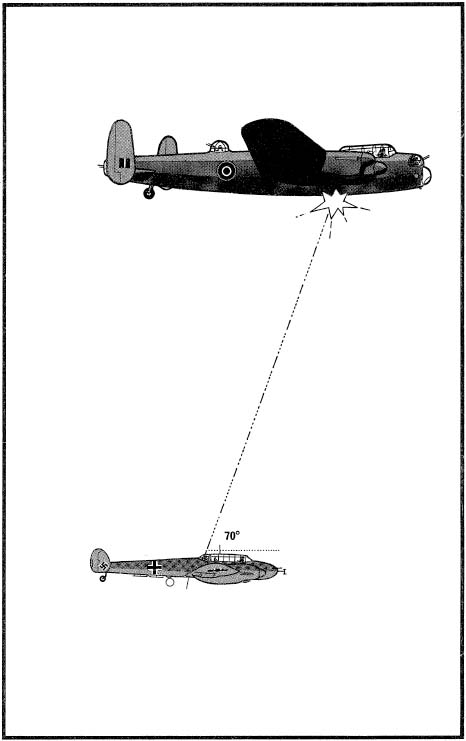

Fig. 22.

Schräge Musik

Attack

The

Schräge Musik

installation allowed attacks to be made from the blind spot almost directly underneath a bomber

,

and this could be continued even if the bomber took mild evasive action.

A number of new devices entered service at about this time. Among them was the SN-2 radar set, which used a longer wavelength and, for the moment at least, was not susceptible to Window, and electronic gadgetry which enabled the fighters to home on emissions produced by the bombers. These last were passive detectors, which, while they gave no indication of range, did not betray the presence of the fighters to the lurking Mosquitos. They also solved the problem of finding the bomber stream.

Whereas standard procedure with forward-firing armament was to dive below the bomber before swimming up from the depths like a shark, a new form of attack now emerged. This hinged on

Schräge Musik

, cannon set in the fuselage to fire upwards at an angle of between 60 and 70 degrees. The idea was hardly new—it dated back at least to 1916—but its widespread application in 1943 was revolutionary. See

Fig. 22

.

The fighter now crept up behind and below the bomber, where it was least likely to be seen. It then formated about 200 feet below and matched speeds precisely, while the pilot took careful aim through a standard reflector sight mounted on the roof of his cabin. The preferred aiming point was the fuel tank in the wing between the fuselage and the engine of the bomber. Hits in this area were usually lethal, and as no tracer rounds were used the bomber crew often had no idea where the firing was coming from. The loss rate of the raiders rose.

The first quarter of 1944 saw both a bad reverse and a resounding victory for the

Nachtjagdflieger.

In fighter combat, the few run up big scores while the many blunder around the sky for little result. These few are an example and an inspiration to others and, as such, have an effect on the force as a whole out of all proportion to their numbers and achievements. Conversely, their loss is devastating. For the

Nachtjagdflieger

, the night of 21/22 January 1944, when not one but two leading

Experten

fell, was a major disaster.

The occasion was a heavy raid on Magdeburg.

Prinz

Heinrich zu Sayn-Wittgenstein had just shot down five bombers to bring his score to 83, making him briefly the top-ranking night

Experte

, when his Ju 88 was caught from behind by a Mosquito. He baled out, but his parachute failed to open. A few miles away Manfred Meurer (65 victories) attacked a bomber from below with

Schräge Musik.

Stricken, the bomber plunged downwards and collided with Meurer’s He 219. Victim and victor fell interlocked in flames. The

Nachtjagdflieger

was devastated by this double loss.